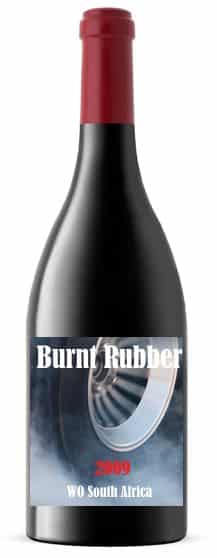

Tim James: Burnt rubber and bitterness – revisiting old battle-scenes

By Tim James, 2 September 2019

1

Ten years is a long time in the wine industry. Has anyone sniffed burnt rubber in their glass of local red recently, or read tales from someone who has? It’s hard now, with such widespread enthusiasm for the Cape’s top wine, to recall how negative much of the international perception was a decade ago. Burnt rubber seemed to be just about all that some British critics could find – most notoriously Jane MacQuitty of the Times, who described the five-star wines and runners-up in Platter 2008 as “a cruddy, stomach-heaving and palate-crippling disappointment.” But not just her (though it was never really an issue for Jancis Robinson, for example).

Ten years is a long time in the wine industry. Has anyone sniffed burnt rubber in their glass of local red recently, or read tales from someone who has? It’s hard now, with such widespread enthusiasm for the Cape’s top wine, to recall how negative much of the international perception was a decade ago. Burnt rubber seemed to be just about all that some British critics could find – most notoriously Jane MacQuitty of the Times, who described the five-star wines and runners-up in Platter 2008 as “a cruddy, stomach-heaving and palate-crippling disappointment.” But not just her (though it was never really an issue for Jancis Robinson, for example).

A deeply worried Wines of South Africa put on a tasting in London in 2009, inviting professional tasters to note down offending wines. Tim Atkin reported that “of the 70 Cape wines we tasted, roughly a third displayed an unmistakable – and unwelcome – South African character”. Though he added that “Rubber, burnt rubber to be precise, was only part of it.” The character hadn’t been noted by South African tasters, and they (we; certainly I) still mostly thought the Brit crits were exaggerating wildly – but they could irrefutably respond, as Tim Atkin did, by asking: “Is it a case of what Australians call ‘cellar palate’, where a winemaker gets so used to tasting his own creations that he becomes blind to their limitations?”

One could in turn respond that, well, another well known phenomenon in wine tasting is suggestibility – which can involve finding the trait that you are particularly expecting to find. This was to some extent corroborated by the findings of wine biotechnology Professor Florian Bauer of Stellenbosch University, who led a project from 2008–2011 to investigate the problem. The report concluded that “there are indeed ‘BR’ related issues in SA wines, but that they do not constitute more than a small percentage of faults”. The team assessed a large number of accused wines and “found that a number of common taints (herbaceousness, brett, reduction and oxidation in particular) were often mistakenly identified as [burnt rubber].”

Suddenly, anyway, the problem seemed to largely disappear. Tim Atkin chaired the “Top 100” competition in 2011, with a skilled winefault-finder, Sam Harrop, at his side. Of the 40 faulty wines they found in the competition, none seemed to involve burnt rubber. But the general accusation remained in the air. Richard Hemming, writing (a touch patronisingly) on jancisrobinson.com in the wake of Cape Wine 2012, found it necessary to discuss that he hadn’t, in fact, found much burnt rubber.

So either the local wine industry cleaned up its act incredibly quickly (including, perhaps, removing overnight the millions of creosoted vine-poles that many thought responsible for the burnt rubber problem), or else perhaps stopped looking for it so hard? It does seem a long time since Atkin et al. have waxed wroth about it. Let’s all be glad if, indeed, any problem there was has been solved so quickly and apparently easily. But what about all the older wines that are now getting such high prices at auction? Should potential buyers be warned that what the likes of the Platter’s Guide thought best a decade back are wines that an arguably intelligent and responsible critic in a major London newspaper considered to be ”stomach-heaving and palate-crippling”?

There was another significant problem that was worrying the spokespeople for the wine industry even a decade earlier – bitterness in our own beloved pinotage. Now, this was a fault that most locals could identify; fortunately, the cellar palate syndrome didn’t kick in here. A lot of research was done, and as I recall a lot of suggestions were made about how to deal with it, in vineyard and cellar. And, yes, the problem has substantially disappeared. Occasionally I do find a trace of bitterness decorating or distressing the last moments of a mouthful of pinotage – both the more old-fashioned big style and the lighter, fresher more modern style. It’s seldom bad, and a hint of it can even add to the interest of the wine.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. He is a taster (and associate editor) for Platter’s. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Eamonn Bolton | 26 July 2020

I have enjoyed wine for over 40 years now and the one ommission in my buying habits is South African red. I am one of those people who are susceptible to picking out the burnt rubber taste and it is a huge disappointment and very off-putting. Occasionally I fall victim to label blindness and buy one. If I don’t spot the country of origin on the label before opening it, I pick it up immediately on tasting.

This is not a bias, it is an unwelcome fact. I hope someone gets to the bottom of it someday.