SA wine history: Concluding the Olifants River journey (for now)

By Joanne Gibson, 13 November 2020

1

‘What is history,’ mused Napoleon Bonaparte, ‘but a fable agreed upon?’

My investigation into claims that the exiled emperor drank wine from the Upper Olifants River Valley has bordered on obsession over the past month or two (see here, here, and here) and I need to walk away from it for now (not least because it seems Paarl could use a little TLC).

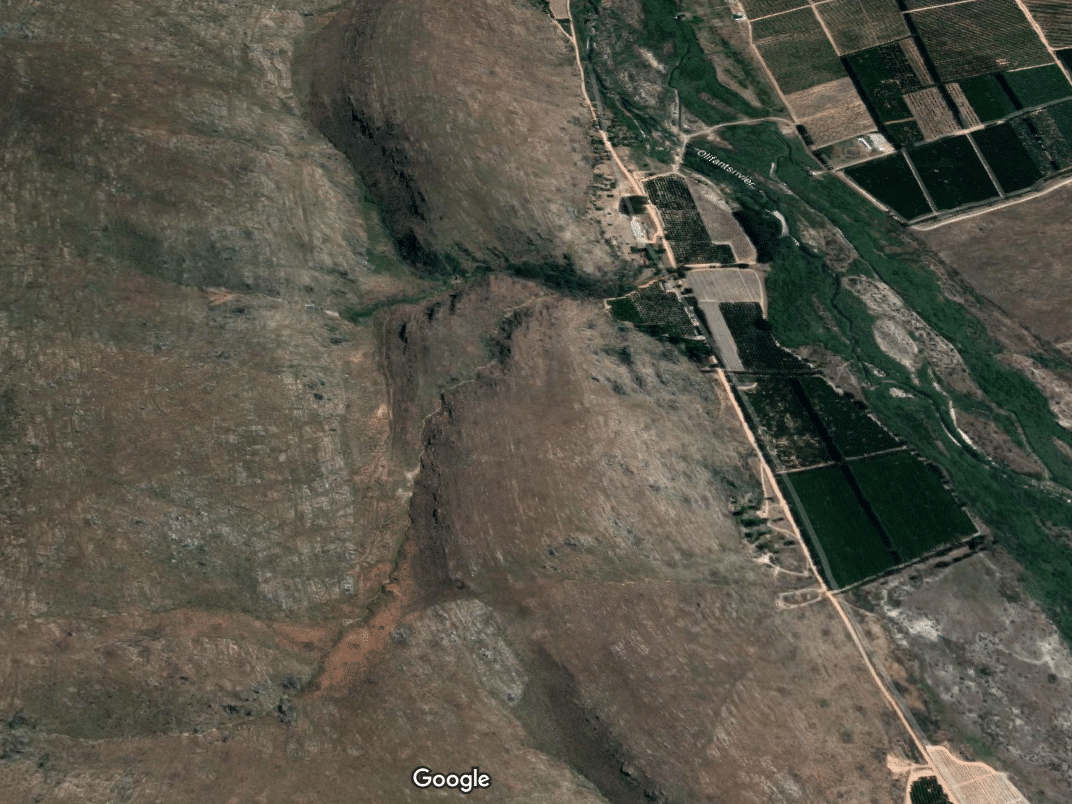

But I do want to wrap things up by focusing on the deep, narrow, fertile valley south of what is Citrusdal today: the farms around The Baths, reached most directly via the old Cartouw pass, and what we know about the wines produced there (in the past and today).

Further evidence has come to light about the Cartouw pass thanks to the journals of Hendrik Swellengrebel, son of a former Cape Governor, dean of Utrecht Cathedral, who made three journeys into the interior of the Cape of Good Hope in the late 1770s. He reached the Olifants River Valley at precisely 9.05am on 14 January 1777, having taken just over an hour to traverse the pass: ‘On the western side it is reasonably good, but on the eastern side it is very rocky and steep,’ he wrote. ‘It needed three-quarters of an hour, without stopping once, to get down.’

By 10.30am Swellengrebel had reached the farm of Schalk Willem Burger: presumably his freehold farm Halve Dorschlvloer (known as Karnemelksvlei today) rather than Misgunt, his loan farm. Either way, Swellengrebel described it as ‘one of the finest farms because of the water, the wild oak trees etc, and especially the fruit trees’.

‘We found lovely grapes here,’ recorded Swellengrebel, although he didn’t mention the local wine (unlike botanist Francis Masson who in 1773 found it ‘sour and unwholesome; which, I think, may be due to their planting their vines in wet, marshy places’). In a letter written in 1783, however, Swellengrebel discussed winegrowing at the Cape in general: ‘Wheat and wine are cultivated between Cape Town and Steenberg and, across False Bay, along the Hottentots Holland mountains and those of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein, to Roodezand [Tulbagh] and the mountains of the Olifants River, and thence along the Piketbergen to the sea.’

Opining that ‘the western districts are well suited for wines, yet the Overberg districts are not’ (famous last words?), he wrote: ‘I have drunk some white wine which could be taken for the best French wine, and I have been told of red wines with the same flavour and aroma as those of Bordeaux… Fustage, like other wooden articles, is extremely dear, and so is transport, for not more than one leaguer [about 575 litres] can be carried in a waggon.’

From that last observation, we can conclude that only small quantities of wine would have made it to the Cape from the Upper Olifants River, with Sir John Barrow lending weight to this argument in 1798: ‘The great distance from the Cape, and the bad roads of the Cardouw, hold out little encouragement for the farmer to extend the cultivation of grain, fruit, or wine, beyond the necessary supply of his own family.’

As I showed in my last column, however, local farmers routinely used the Piekenierskloof pass rather than the more direct but also more dangerous Cartouw pass for their larger loads and more cumbersome wagons. ‘It is not as difficult as the Cartow [sic] but longer,’ agreed Swellengrebel.

What’s more, the production capacity of some Upper Olifants River cellars definitely seems to have been larger than would have been needed for home consumption (11 leaguers inventoried in Schalk Willem Burger’s estate in 1782, for example; 13 leaguers inventoried in Barend Lubbe’s estate at Grootvalleij in 1785). Meanwhile, the estate inventory of Gerbregt Christina Pretorius in 1804 proves that Abraham Mouton of Modder Fontein was selling his wine because she still owed him for two half-aums (roughly 145 litres) as well as five bottles of brandy.

While investigating the Mouton/Brakfontein claim to Napoleon fame, I was contacted by a historian named Alex Giardini who grew up on a farm just south of Citrusdal and researched the history of the area for his Honours thesis. ‘I heard somewhere that wine from the farm Kardouw was sent to St Helena,’ he said. ‘I really cannot remember [who told me] to be honest.’

Kardouw (known as Cartouw in the old days) is right at the foot of the old disused pass and today forms part of ALG Estates along with a handful of other farms in the Van der Merwe family (including Karnemelksvlei). Having married into the family, Stellenbosch University viticulture and oenology graduate Grettchen van der Merwe has set about exploring the potential of Piekenierskloof grenache and cinsault, and she has named her range Kardouw Wines.

Was she perhaps able to unearth anything linking her in-laws’ farm to Napoleon? ‘No, but Kardouw was originally a wine farm,’ she confirms. ‘The original cellar is still on the premises – it’s pretty old.’

Interestingly, Cardouw was the name chosen in the late 1990s by the old Goue Vallei/Citrusdal Cellars co-operative for its top-end range, but all the material I can find merely attributes the choice of name to the pass (and the Khoisan word for ‘narrow passage’) rather than to a farm once known for its wine.

So there I’ve decided to leave it, for now, but I remain hopeful that someone will find some old records in a dusty cellar someday, and that we’ll be able to reach agreement upon this fable.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Masson, Francis: An Account of Three Journeys from the Cape Town into the Southern Parts of Africa, Philosophical Transactions for the Royal Society of London, vol.66 (1776), pp.268-317

Swellengrebel, Hendrik jr: Briefwisseling oor Kaapse sake 1778-1792 (ed GJ Schutte), Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 1982

Swellengrebel, Hendrik jr: Journalen van Drie Reizen in 1776-1777, (ed GJ Schutte), Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 2018

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za.

Comments

1 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.

Martli Slabber | 18 November 2020

Hi Joanne

The -douw part of the name Cardouw probably echo a word from the San: all the places where one can cross the mountain ranges in the area/ a pass, ends in a -douw. Kriedouw, Nardouw, Biedouw, Cardouw, Krakadouw, and further out, Kareedouw, – and Grabouw probably is also a deformed derivative..

The Napoleon wines probably came from the whole valley – my oupa used to tell that it was made on our farm, Hexrivier…. 😉 We still have an orchard, the vines now long gone, that is called Ou Wingerd. Sadly, in all the old archives, I cannot trace the type of grape. My great-great grandmother was the sister of Abraham Mouton who lived on Brakfontein. She stayed on Hexrivier, and her sons inherited the farm.