There’s no doubt that the world we know – and trade with – is in turmoil. At home we have the uncertainties surrounding the GNU/coalition. The ANC ignores the DA even as it cannot manage itself or its component parts. It is so riven by division that the president finds himself unable to fire a minister caught red-handed stealing and lying to parliament about it. Abroad we have the disruptions of Trumpism – made more colourful with threats of increased duties and diminished aid.

Wine producers may be worse off than many other exporters: our key trading partners have either hiked taxes and excise to stave off a fiscal crisis or are themselves so occupied by their own political issues that survival alone dominates their thinking. And then there’s the state of the alcoholic beverage market worldwide – with reduced consumption (especially among the under 40 year olds) and increased anti-alcohol pressure from the dishonest killjoys at the WHO. It’s not an easy time to be in business – especially not the wine business.

This makes the present moment the ideal time to go out and increase market share. With everyone hiding under the parapet there is less investment in brand-building and more investment in discounting: producers everywhere are looking at their growing unsold inventories and trying to fix the problem of burgeoning stock by slashing prices. What follows becomes a race to the bottom, with retailers (and consumers) holding the aces and the supplier sector perpetually under the whip.

It gets worse. If everyone shaves 10% off their offers, all prices drop equally and the status quo remains. With less money available for brand building (or even for promotion) budgets are pared back. Retail sales surge initially – but then consumers no longer feel any serious inducement to shop, and so another round of cost cutting inevitably follows.

Instead of flirting with the slippery slope of value destruction, savvy producers recognise that this is the time to build brand – counter-intuitive though this may be in the midst of collapsing prices and reduced demand. No one thinks long term in the midst of what appears to be a short term crisis (but which may in fact last a lot longer than we are willing to imagine). However there is no other way forward. There’s no happy ending to a discount war.

While competitors are cutting price, the smart move is to use the tumult and turmoil to show strength, not weakness. Ask yourself why the truly great (non-fashion) luxury brands never hold end-of-season sales. Price and brand are inextricably linked: give ground on price and inevitably your image will suffer.

Cape wine has been through the wringer many times in the past half century. In the isolation era it could only be sold with massive discounts. After 1994 we accepted the prices offered by the international supermarket buyers (partly because they appeared to offer sufficient margin, partly because the years of skelm trading in the 1980s had left the industry without any real pricing benchmarks). Again after 2008 (and then again straight after Covid-19) trading terms were forced upon us. Brand South Africa never really looked strong enough to resist.

Things are a little different now: the world has come to see that our offering is unique, that we over-deliver at all price points, that we are not simply a country of supermarket wines. There will never be a better time to address the tarnished image of the recent past.

Piet Beyers, who knows more than a little bit about wine and about the international luxury goods trade having worked at a high level for various of the Rupert entities, uses a helpful analogy to describe the essentials of the fine wine business. He says it’s like a three-legged pot where each leg plays a crucial role. One leg is great fruit, the other leg is quality wine making, the third leg is appropriate wine marketing. You cannot afford to be without any one of these three pillars. For too long we have relied on the grapes and the oenology and assumed that the marketing would take care of itself. The results of that approach speak for themselves.

Now for the first time in the modern era our vineyards are looking good, we are making fabulous wines, and there’s a groundswell of positive sentiment about Cape wine in the market. We must hold onto our gains AND we must advance while everyone else is on the retreat. To fall back onto discounting would be to undermine the value of the recent achievements in image building. This may be the hardest thing we have ever attempted to do: to hold firm despite the enormous downward pricing pressure of the bear market.

Wine reputations are a complicated interaction between perception and reality, where the weight of a brand name, a storied maison, or a prestigious appellation often holds more sway than the liquid in the glass. While quality should, in theory, dictate the value and desirability of a wine, the influence of branding, legacy, and marketing often eclipses marginal differences in intrinsic characteristics.

Consumers, both seasoned connoisseurs and casual drinkers, lean on established brands as a proxy for quality. The names of Bordeaux first growths, the grand marques of Champagne, or revered Burgundian domaines are etched into the wine world’s consciousness. These producers have, over decades or even centuries, cultivated an aura of excellence that persists irrespective of vintage variation or stylistic changes.

Local analogies are easy to draw. When it comes to Bordeaux-style red blends, there’s an aura of both prestige and reliability to Kanonkop and Meerlust that’s not easily lost; Graham Beck is not going to be knocked off its pedestal for making top Cap Classique any time soon; and the wards of Hemel-en-Aarde have now pretty much taken a stranglehold on Pinot Noir

For many buyers, purchasing a bottle from an iconic producer guarantees a certain level of quality, even if a blind tasting might reveal similar or even superior quality from lesser-known properties. This trust in branding reduces the cognitive effort required to assess every bottle individually. Instead, consumers rely on the safety of reputation, making established brands more resilient in the marketplace than wines judged purely on their organoleptic merits.

Additionally, well-established wine brands often eschew the scrutiny that comes with blind tastings, where their wines could be evaluated purely on merit rather than legacy, further reinforcing their dominance in the market. Mullineux, Sadie, Savage and the rest of the A-list are only ever going to show their wines sighted, under the most carefully controlled circumstances, and nobody should be surprised that this is the case…

The idea that great wine is inherently superior to merely good wine is complicated by the subjectivity of tasting. While professional critics and sommeliers are trained to parse out the minutiae of aroma, flavor, structure, and balance, the differences between wines of similar quality levels can be incredibly subtle. Moreover, a deep level of engagement with the subject is required to care at all. Watch this hilarious but also mildly painful Instagram reel to discover how many people really feel about wine:

View this post on Instagram

Consider, if you will, two examples of Chenin Blanc from adjacent parcels in the Swartland, produced with similar techniques, which might exhibit only marginal variations in fruit concentration, freshness or any other important measure. Yet, one from a high-profile producer with a established reputation will command a significantly higher price than a virtually identical wine from a less famous neighbour. The perceived difference in quality is often exaggerated by psychological bias and the halo effect of branding.

It’s not like wine criticism and scores don’t play a role in reinforcing the dominance of established brands. A 100-point wine from an iconic estate cements its desirability, even if the difference between a 97-point competitor is negligible to most palates. The fear of missing out (FOMO) and the desire for social validation further skew the wine market in favor of brands with historical clout.

Additionally, the role of wine auctions (yes, Strauss & Co, we’re looking at you) and secondary markets amplifies the phenomenon. Collectors seeking blue-chip wines from revered estates drive up demand and prices, further widening the gap between brand reputation and intrinsic wine quality.

While wine quality remains a crucial factor, its impact on consumer perception is often overshadowed by brand prestige, marketing, and social influence. Marginal differences in organoleptic qualities are frequently lost amidst the weight of reputation and perceived status. This phenomenon underscores the reality that in the world of fine wine, the story behind the bottle increasingly matters as much – if not more – than what is inside.

I’m still looking for some specially great value local chardonnay. But having disappointingly realised a few weeks back that it’s pretty naive to hope for something good enough for the likes of us under a hundred bucks. I’ve raised my sights somewhat – hopefully good value stuff but not exactly cheap. My chance to do so without laying out my own hard-earned cash on some bottles came at last week’s trade tasting of that excellent and ever-expanding wine distributor Ex Animo. Of the 57 releases (clearly not all of them new) they were showing, eight were chardonnays, a decent proportion.

Nine, in fact, if you include (as I was more than happy to in my selective perambulation) Pieter Ferreira Cap Classique Blanc de Blancs 2018. Seven years on the lees have added to its ripe-apple gorgeousnessness without taking away from its freshness, rounding it out without its losing focus or precision. I’m sipping the previous vintage, 2017, as I write, and it also has a lovely succulent, fresh and subtly flavourful firmness. About R540, which is not a little money, but pretty good value – especially when you compare the quality with that of hundrum supermarket champagne (Moët Imperial, for example) at a few hundred rands more, whose success amongst all the Cap Classique is explicable only by ignorant snobbery. Incidentally, the prices I am giving here are obviously approximate; they derive from the Ex Animo trade prices to which I’ve added 35% to allow for a retailer mark-up (which is quite likely to be more rather than less than this, I’m afraid); a few of them might only be taking on their annual increase on 1 March, to make it complicated; but to work with those March prices is the best I can do.

So what of the non-bubble chardonnays? A great, and rather interesting, place to begin is Restless River, the Hemel-en-Aarde property which Craig and Anne Wessels have resolutely built over the last few decades into a model of finesse and integrity. Their more modestly priced Vineyard Selection Chardonnay comes, in the European tradition, from top terroir but younger vines. Both the 2023 Selection (R340) and the 2022 Ava Marie (R620) are predictably rather brilliant. The 2022 is from the better vintage, and that wine is grippier and more assertively “youthful”, asking for a few years at least, if possible. The flagship Ava Marie is actually readier to drink. This wine has a history of very good, positive ageability, but I wonder if this 2022 will gain much, even over a few years. It’s absolutely lovely now, more deeply serene and harmonious than the other wine. Neither of these is exactly cheap, but the Vineyard Selection is arguably the better value this release. Ava Marie is one of the Cape’s finest examples, and less expensive than a lot of others in the top flight, and even this year it’s a gratifying buy – if you have that sort of money.

The next most expensive chardonnay at this tasting has much less of a pedigree – if you discount the eminence of its producer as a maker of red wine. Beeslaar Chardonnay 2023 (R460) comes from widely-sourced fruit and is, I think, the third vintage of it made by Abrie Beeslaar, formerly of Kanonkop (where he still consults). It’s modestly oaked but a hint of vanilla persists. Although the alcohol is modest, there is a fruit-richness to the wine, and a hint of sweetness on the palate.

Chris Williams has now introduced a chardonnay to the impressive vineyard-specific Geographica range of his The Foundry label. Alethiea 2023 (the name apparently signifies ‘truth’ in ancient Greek) comes from the remote and lovely Tierhoek farm in Piekenierskloof, matured in a mix of clay and seasoned oak. At about R350, it’s close in price to Restless River Vineyard Selection and I think it’s great value for that price – very pure but complex, lively, fresh and elegant. One of my favourite wines at this tasting, and a great addition to the Cape’s chardonnay repertoire.

It’s looking to me, from this tasting at least, as though R350 is where really serious chardonnay starts. Julien Schaal’s Evidence Chardonnay 2023, from Elgin, is not too much more than that. It’s a suave, handsome and assured, modestly but effectively oaked wine, fairly understated and elegant, but with full flavours (I loved the hint of fennel I found).

Now we dip below R300, and I’m not sure after all, that we need to start at R350 for the grand stuff – certainly not for some pretty serious drinkability. Callender Peak Mountain Vineyards Chardonnay 2022 (R275), from the cool fruit-growing Agterwitzenberg Valley in the Ceres Plateau WO (we really are moving around in this little survey) is made by Donovan Rall, which counts plenty. It’s on the richer, creamy side, with some toasty oak, and there is a good freshness too.

Then another significant dip, to Copper Pot Chardonnay 2023, made by John Seccombe of Thorne & Daughters. The Ex Animo website and many other retailers quote a price of around R180, but it looks like there’s to be a pretty large, 20% increase at the end of the month – so if you want one of the better value chards around, get in before then. It’s gently rounded and pleasant, with a notably lemony core.

And last, Van Loggerenberg’s Break A Leg Chardonnay 2023, which looks set to stay well under R200 – about R175 to be more exact. Really nicely balanced with a characteristic feeling of Van Loggerenberg lightness and elegance; unoaked, bright and fresh but with the lemony note subdued. There’s more competition around for good unoaked chardonnay (I’ve mentioned Glenelly before), which is a style I really like, but I know for some people it’s not quite the thing. This is good wine, though.

One last wine – a total diversion from my theme. I was rushed at this tasting and limiting myself to chard, but at the last minute couldn’t resist trying Nuschke de Vos’s Vulpes Cana Cabernet Sauvignon 2023 (R420). Nuschke used to make one of the Stellenbosch cabs I particularly liked, at Reyneke,and this addition to her own young label is also from the Polkadraai Hills. Matured in only old oak, it’s light, pure, focused and properly dry, with authentic cab flavours. There are certainly not many traditional (richer, oakier, sweeter, more powerful) Stellenbosch cabs that I would rather drink, especially in youth. It’s just delicious. And the label shows a cute, bushy-tailed and curled-up little fox that would presumably rip my throat out if it could.

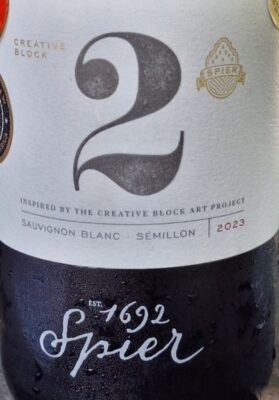

At R160 a bottle, the 2023 vintage of Creative Block 2 from Spier punches above its weight. Grapes sourced variously from Durbanville, Stellenbosch and Darling, it’s a blend of 86% Sauvignon Blanc and 14% Semillon, a small portion of the latter fermented in oak.

At R160 a bottle, the 2023 vintage of Creative Block 2 from Spier punches above its weight. Grapes sourced variously from Durbanville, Stellenbosch and Darling, it’s a blend of 86% Sauvignon Blanc and 14% Semillon, a small portion of the latter fermented in oak.

Striking aromatics of lime, soft citrus (naartjie), a definite herbal edge but also granadilla and blackcurrant. The palate shows super-concentrated fruit matched by punchy acidity, the finish dry. It’s showy but irresistibly so. Alc: 13.72%.

CE’s rating: 93/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

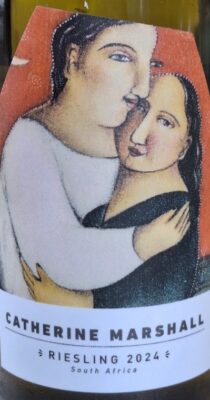

So much to like about the Riesling 2024. Grapes from two sites in Elgin, one in the Kogelberg Biosphere and the other on higher slopes close to the Groenlandberg, fermentation involved inoculation with a commercial yeast suited to the variety.

So much to like about the Riesling 2024. Grapes from two sites in Elgin, one in the Kogelberg Biosphere and the other on higher slopes close to the Groenlandberg, fermentation involved inoculation with a commercial yeast suited to the variety.

Lime, green apple, flowers, an attractive herbal note and flinty reduction on the nose. The palate’s not exactly lean (the residual sugar is 8.3g/l necessary to offset the total acidity of 7.1g/l) but it has an enchanting clean, sappy quality – pure and poised, the finish dry. Price: R180 a bottle.

CE’s rating: 91/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

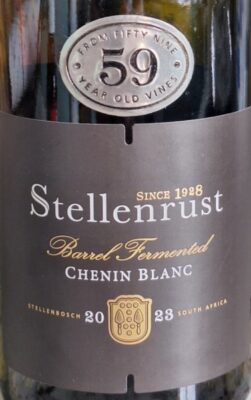

Bottelary is pretty special country when it comes to old-vine Chenin Blanc having given us Radio Lazarus from Alheit, 1947 from Kaapzicht and the Barrel Fermented from Stellenrust. Planted in 1964, this latter vineyard’s age in the year of production is proudly displayed by a badge on the bottle.

Bottelary is pretty special country when it comes to old-vine Chenin Blanc having given us Radio Lazarus from Alheit, 1947 from Kaapzicht and the Barrel Fermented from Stellenrust. Planted in 1964, this latter vineyard’s age in the year of production is proudly displayed by a badge on the bottle.

The 2023 vintage saw fermentation take place in barrels, of which 16% were new, the process taking two months to complete. Maturation lasted a further five months, 57% in oak and 43% in concrete eggs.

Expressive aromatics of honeysuckle, thatch, quince, yellow peach and pineapple plus some leesy complexity while the palate is succulent with bright acidity and a savoury finish (alc: 13.5%). Rich but not overly sweet, dense but not monolithic, it’s a lot of wine for the relatively modest price of R275 a bottle.

CE’s rating: 94/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

It may come as a bit of a surprise to hear that I am not a massive fan of wine trade fairs. From my experience, trade shows are invariably expensive for exhibitors and often deliver disappointing results, with a poor return on investment in terms of new leads and clients. Somewhat ironically, I say this as someone who began their business career in the trade show industry after university.

After completing my business degree, I was appointed the project manager in Washington DC, USA, for the innovative and ground-breaking “Made in USA Trade Fair 1993” that was held in Mid-Rand, Johannesburg, in November at the World Trade Centre… (yes, for those that can remember, the very same venue the Afrikaner Weerstands Beweging (AWB) tried to ram a mini-armoured personnel carrier through the front doors during the ongoing political meetings negotiating the peaceful handover of power from the old apartheid government to a new political order.)

The “Made in USA Trade Fair” brought hundreds of Fortune 500 American companies back to South Africa, by express invitation by the then ANC Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Thabo Mbeki, who would of course later eventually become one of South Africa’s democratically elected presidents. Obtaining this invitation from the ANC, pre-dropping of sanctions and pre-democratic elections, stood as a particularly significant milestone for the organisers.

At this point in time, the language of international economic sanctions and the wider disinvestment culture was quickly losing favour on all sides of the political spectrum as politicians from all parties started to fully appreciate the true size of the economic challenges that would lie ahead for a new democratic South Africa, whichever party won power and took office.

Certainly, the financial outlay for the American companies coming out to South Africa to exhibit for three days would have been substantial. Yet the potential opportunities for a company successfully re-entering a ‘new’ market would have been incredibly lucrative. Being the first to get boots on the ground, or in this case, polished brogues, was seen as incredibly important considering the potential size of the South African economy and its standing as a gateway into the rest of Africa.

My experience of wine tradeshows however is a little bit like entering wine competitions, both normally at significant cost, in that the real work only really begins after the show is over or after your wine has hopefully won an award or a medal. Too many wine producers fail to fully exploit the true potential of new contacts made at wine fairs in a similar way that many producers win their medal and then simply seem content to frame the award and pop it on the walls of their tasting rooms with no subsequent follow up marketing plan or media work.

Whereas in the past, trade fairs were seen as a pretty established alternative method to make inroads into new foreign markets to meet new potential agents, importers and clients, we have unfortunately over the past couple of years witnessed The London Wine Trade Fair, Prowein and Vinitaly turning into somewhat cumbersome money-making ventures offering wineries and exhibitors a diminishing return on their investment.

But it seems with the tough economic times starting to bite everywhere, the tide is starting to turn as more and more producers have decided to shun the Prowein-type monster shows that have almost started to consume themselves. So, having heard increasingly good intel on the value of the Wine Paris Vinexposium from many of my European counterparts, I decided to dip my toe in and attend with media accreditation.

In much the same way large monster shows like Prowein have started to lose support, the same evolution definitely occurred over the years with Vinexpo in Bordeaux, a show that grew ever bigger and ever more expensive, but alas, also less and less relevant, until it reached tipping point where the economics of attending simply did not add up for foreign wineries, especially those from far-flung South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

The Wine Paris show, however, is the reimagined expression of a wine trade fair that in many ways returns to the basic principles of what made many of these international shows so popular when they started out all those years ago. Having just returned from Paris, I can confirm that this year’s event was indeed a very interesting and valuable experience for me, and from what I could gather from the many exhibitors I spoke to, the halls were awash not only with fine wine but also positivity and optimism.

The “International Hall 4” was also home to a number of top South African producers, all of whom seemed far more organised, focused and prepared in regard to arranged appointments and structured schedules than I have seen for many a year. By day two of the show, Mike Ratcliffe, owner of Vilafonté property in Paarl was already singing the shows praises, now securely positioned on the Vinimark stand, to where Vilafonté have recently moved local South African sales and distribution.

But others, including Johann Reyneke of Reyneke Wines in the Polkadraai Hills, seemed inundated with visitors and appointments, as were regional Robertson stalwarts De Wetshof Estate, where Johann de Wet was beaming with positivity. Likewise, Nicolas Bureau, the CEO of Glenelly Estate, and no stranger to international wine trade fairs, seemed very upbeat with the quality of visitors and the response to his estate’s wines.

Wineries attending these events at considerable expense, clearly seem to be doing so with more preparation, planning and intent. But more than that, for the first time in a long while, I experienced a positivity and optimism not only among the South African producers attending, but also on the Wines of California stand, the Napa Valley stand, the Wines of Lebanon stand, and the Wines of Switzerland stand, all of which were scheduled destinations for me.

The wider global wine trade has been a somewhat sombre environment of late, with all producers, importers and agents preoccupied with the cost of living crisis, falling consumption figures and the rise of “abstinence influencers” among other industry problems. I for one however, want to take my hat off to the Wine Paris organisers who have delivered a very well organised, well attended, and engaging trade fair. But of course, now the real work begins for producers, following up and making good on all the leads generated.

With both the London Wine Trade Fair coming up in May and then Cape Wine in September in Cape Town, I certainly plan to attend both events with hopefully an extra skip in my step and plenty of renewed positivity for the future of an evolving wine trade.

How much to expect from Cinsault? Some of South Africa’s top winemakers take it very seriously indeed – the Mullineuxs, for instance, making one from a Wellington vineyard planted in 1900 under the Leeu Passant label, while Pofadder from Sadie and both Geronimo and Lötter from Van Loggerenberg are other notable examples.

How much to expect from Cinsault? Some of South Africa’s top winemakers take it very seriously indeed – the Mullineuxs, for instance, making one from a Wellington vineyard planted in 1900 under the Leeu Passant label, while Pofadder from Sadie and both Geronimo and Lötter from Van Loggerenberg are other notable examples.

Nadia Langenegger of Waterkloof takes a more modest approach with her version under the Seriously Cool label, the result in the case of the 2023 vintage nevertheless entirely charming.

Grapes from Stellenbosch vineyards planted in 1964 and 1974. Wholebunch, partial carbonic maceration before maturation lasting 12 months in second- and third-fill 600-litre barrels.

An extravagantly perfumed nose with notes of red cherry, strawberry rose and herbs while the palate is lean and fresh with powdery tannins. Elegant, lively and not out of reach at R160 a bottle.

CE’s rating: 90/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

A bottle of Blanc de Noir 1993 was opened in the spirit of inquiry rather than anything else, but it proved far better drinking than might reasonably have been expected. Deep orange in colour with a copper tinge, the nose showed campari-like notes of orange, herbs and spice while the palate had good texture and was full of verve. Hardly profound but very little decay in evidence. It rated Three Stars in the 1994 edition of Platter’s and was described as “Off-dry, ripe strawberry palate; lively clean.” The 1992 vintage was from Pinotage so presumably this was, too. Alc: 11.5%.

A bottle of Blanc de Noir 1993 was opened in the spirit of inquiry rather than anything else, but it proved far better drinking than might reasonably have been expected. Deep orange in colour with a copper tinge, the nose showed campari-like notes of orange, herbs and spice while the palate had good texture and was full of verve. Hardly profound but very little decay in evidence. It rated Three Stars in the 1994 edition of Platter’s and was described as “Off-dry, ripe strawberry palate; lively clean.” The 1992 vintage was from Pinotage so presumably this was, too. Alc: 11.5%.

The co-operative was then served by 116 farms belonging to 90 members, processing 22,000 tons of grapes a year, total production equating to 1,5 million cases.

I’m certainly not the wine-geek I once was. More and more I care less and less about such things as pH, time spent on skins this vintage compared with last, the direction of the rows of vines, the precise age and size of barrels, and the like. Possibly it’s to do with increased difficulty in remembering the stuff I once knew (even about last year’s time on skins), but somehow I just don’t find the fine details and explanations as memorable, let alone fascinating, as I once did. I don’t regard this as cause for either self-congratulation or self-castigation. But it does make for a less complicated relationship with wine – and, anyway, my interest has expanded from the liquid itself to the culture and history, landscape and people, that produce the stuff.

Then along comes sherry. And I get sucked in again. In fact, sherry could well illustrate an earlier geekiness and subsequent forgetting. I used to know a lot about sherry – read the books, twice visited Jerez de la Frontera in Andalusia and had amazing tours of bodegas with experts, did some extraordinary tastings (I do actually recall one of them, in the Alcázar of Jerez, of old great amontillados that counts as one of the great aesthetic – dare I say?– experiences of a lifetime). Sherry is surely just about the most complicated thing in the whole of wine, I think, and much of the subtle detail about all the permutations has now grown fuzzy in what passes for my mind.

Recently, I organised a tasting for my group around the products of the Bodegas Tio Pepe, so I had to brush up. It was a fascinating tasting, starting with the standard big-volume (but highly respected) Tio Pepe Fino, matured by fractional blending in a solera – matured with that famous layer of yeast (“flor”) protecting the wine from oxidation but working various magical things upon the very lightly fortified wine. That has an average age of four years (some components of the solera necessarily younger, some older). Then we followed developments of that exact same basic wine. Firstly through an “En Rama” version that’s only very lightly filtered and stabilised. After that it was a question of age, in the “Palmas” series of annual barrel selections of Tio Pepe wines with average ages of six, eight and ten years, showing increasingly greater complexity and intensity.

Already after four years, the layer of yeast starts to thin out, as the nutrients it feeds on are consumed and unreplenished by very young wine. Once a fino gets to about ten years, the layer of yeast covering the wine in its two-thirds-filled barrel has become decidedly thin and patchy. The wine is now starting to age substantially through oxidation, and that character is very noticeably adding to the flor character.

Any remaining flor is now defeated by a light fortification. From this point onwards, the wine ages only oxidatively and is called amontillado. We tasted two excellent old amontillados – both originating as finos in the Tio Pepe solera. Del Duque is the regular rare old amontillado label of Gonzalez Byass, owners of Tio Pepe, the wine having an average of 30 years spent in old American oak casks. The other was another selection in the Palmas series. The single cask from which the Cuatro Palmas was taken in 2024 had an average age of 55 years. Some of the wine blended in it would have been in its 70s (like a few of the tasters in my group). The wine is extraordinary, like Del Duque but a little more so, much darker than the other wines, pungent, hugely concentrated and complex. Admittedly, I suppose, these old amontillados are an acquired taste, but my word, it’s one worth acquiring.

To anyone whose eyes haven’t glazed over by this time, I will say something about my revived geekiness. Galvanised by the idea of presenting a sherry tasting I consulted books and googled like a proper geek. I managed to get hold of the technical information about the wines (the Bodegas Tio Pepe website is very good, but didn’t have details of the latest release of the Palmas wines, so Michael Fridjhon of importer Reciprocal kindly chased them).

But, looking as a revived geek at the specifications of the amontillados, I was astounded by some of the numbers. That Cuatro Palmas (2024 release) has an alcohol of 21.5%, compared to the original Tio Pepe’s 15.5%. That’s the result of all those decades of evaporation, and not surprising to me. But I also saw that the residual sugar had increased from less than 1 g/L to 7 g/L, and that did surprise me. Could concentration have done that? Could the wine have been sweetened a little at the end? But amontillado these days is not allowed to be sweetened (usually), and Gonzalez Byass say that these Palmas wines are bottled without any manipulation beyond a very coarse filtering. I couldn’t find any explanation in my sherry books or online (though I didn’t venture into some of the very technical academic papers about sherry).

Fortunately, I managed to consult the great sherry expert (and owner of Equipos Navajos, perhaps the most esteemed bottler of a range of sherries these days), Jesús Barquín, whom I’d met in my visits to sherry (we bonded a little over the strength of our shared contempt for the claims of biodynamics, incidentally). He explained to me that sugars do not dissipate at all as wine ages oxidatively, as with total acidity. With the great age of these amontillados, such sugar levels are entirely possible. “There has to be a correlation between these two magnitudes (sugar and acidity) so as to discard any suspicion of forbidden manipulation.” And lo and behold, I was able to check the total acidity of the Cuatro Palmas, and it too had increased hugely. Acetaldehydes had gone down, glycerol gone up, in case you wondered.

Geekish question answered. I’d forgotten how much happens with sherry and how intricate it is. To look at the standard Tio Pepe and see what one or three or five decades – together with a lot of careful nurturing – can do to it is to see one of the great marvels of wine. (Though not widely enough appreciated these days: a bottle of a great old amontillado, or oloroso or palo cortado, costs less than a fairly modest international pinot or cabernet, often much less. But of course, you don’t need the numbers, or an understanding of the processes, to marvel at the taste. It does help me more to think of those dim cathedral-like bodegas in hot Jerez, with endless rows of dark old barrels of wine being guided and cared for so carefully by custodians helping nature on one of its most rewarding and interesting collaborations with us.

Gonzalez-Byass sherries are imported to South Africa and available from Reciprocal, the Palmas range in very small numbers.