This year’s Chenin Blanc Report convened by Winemag.co.za and sponsored by financial institution Prescient Fund Services is now out. There were 63 entries of single-variety Chenin Blanc and 15 Cape White Blends (defined as any blend containing a Chenin Blanc component of more than 15% and less than 85%) and these were tasted blind (labels out of sight) by a three-person panel, scoring done according to the 100-point quality scale.

The 10 best wines overall are:

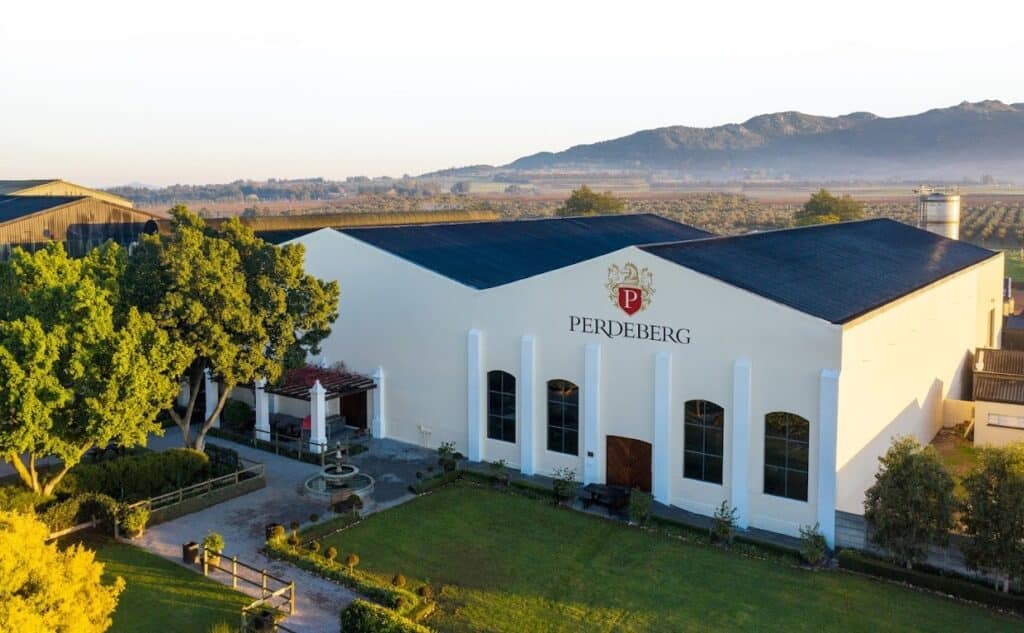

Perdeberg The Dry Land Collection Courageous Barrel-Fermented 2024

Price: R185

Wine of Origin: Paarl

Abv: 14.1%

Winner of a set of Nachtmann glasses worth R2,500 from warewashing specialist Winterhalter.

Durbanville Hills Collectors Reserve The Cape Garden 2024

Price: R160

Wine of Origin: Durbanville, Cape Town

Abv: 13.36%

Bellingham The Bernard Series Old Vine Limited Release 2023

Price: R265

Wine of Origin: Coastal Region

Abv: 13.5%

Perdeberg The Dry Land Collection Rossouw’s Heritage 2023

Price: R205

Wine of Origin: Coastal Region

Abv: 13.78%

Winner of a set of Nachtmann glasses worth R2,500 from warewashing specialist Winterhalter.

Online wine shop Getwine is offering all of the top wines for sale – buy wine.

Chenin Blanc is one of the world’s most versatile grape varieties, capable of producing wines in all manner of styles and at all levels of the market. As recently as 1990, it comprised around 35% of the total area under vineyard in South Africa but in the period after political transformation, the tendency was to replace it with more fashionable red grape types and much was ripped out. It nevertheless remains the country’s most widely planted, making up 15 913ha or 18.4% of the total 86 544ha currently under vine.

Moreover, there has been a growing awareness that the variety had a particular affinity to local growing conditions and there is also a sense that mature vineyards can play a key role in producing wines of excellence. Based on industry convention, old vines are defined as being at least 35 years of age , and of the 4 879ha registered as such, approximately half of this is Chenin.

As for Cape White Blends, these make for an important, if niche, category. No official definition exists but our proposal is that such wines can be made from any combination of varieties as long as they include a significant Chenin Blanc component, specifically more than 15% and less than 85% – the wines that result are often compelling in their complexity and, moreover, no other wine region in the world can lay claim to them.

The average price of the 47 wines to rate 90-plus is R259 a bottle and of the Top 10 is R300.

The Chenin Blanc offering the best quality relative to price is the Reserve Barrel Fermented 2023 from Paarl cellar Windmeul with a rating of 90 and selling for R110 a bottle.

To read the report in full, including key findings, tasting notes for the top wines, buying guide (wines ranked by quality relative to price) and scores on the 100-point quality scale for all wines entered, download the following: Prescient Fund Services Chenin Blanc Report 2025

Watch judges’ comments.

This year’s Shiraz Report convened by Winemag.co.za and sponsored by multinational financial services company Prescient is now out. There were 71 entries and these were tasted blind (labels out of sight) by a three-person panel, scoring done according to the 100-point quality scale.

The 10 best wines overall are as follows:

Raar Carbonic Maceration 2024 (Riebeek Valley Wine Co)

Price: R165

Wine of Origin: Swartland

Abv: 13.5%

Winner of a set of Nachtmann glasses worth R2,500 from warewashing specialist Winterhalter.

Online wine shop Getwine is offering all of the top wines for sale – buy wine.

When it comes to Shiraz, two broad stylistic camps are typically identified: the overtly aromatic, medium-bodied yet densely structured wines of France’s Rhône Valley, and the deeply coloured, plushly fruited examples most famously associated with Australia’s Barossa.

Shiraz and Syrah are, of course, two names for the same grape. The former is often used to suggest power, the latter restraint—but in practice, the distinction is far from absolute.

In South Africa, Shiraz plays a significant role, accounting for 8,340ha or 9.6% of the country’s 86,544ha under vine—second only to Cabernet Sauvignon among red varieties.

The average price of the 36 wines to rate 90-plus is R284 a bottle and of the Top 10 is R237.

Offering the best quality relative to price is De Wet 2023 with a rating of 91 and selling for R76 a bottle.

To read the report in full, including key findings, tasting notes for the top wines, buying guide (wines ranked by quality relative to price) and scores on the 100-point quality scale for all wines entered, download the following: Prescient Fund Services Shiraz Report 2025

Watch judges’ comments.

Unfortunately, I can’t give my financial advisor much to do, but Peter Hawker is a serious wine lover and we have stuff other than money to chat about. Recently he gave me lunch at A Tavola in Cape Town, sharing a bottle of St Leger Chardonnay 2022 he’d brought (very good it was, though deserving more time in bottle), and lending me this book: My Journey with Wine, by May-Eliane de Lencquesaing.

Unfortunately, I can’t give my financial advisor much to do, but Peter Hawker is a serious wine lover and we have stuff other than money to chat about. Recently he gave me lunch at A Tavola in Cape Town, sharing a bottle of St Leger Chardonnay 2022 he’d brought (very good it was, though deserving more time in bottle), and lending me this book: My Journey with Wine, by May-Eliane de Lencquesaing.

Mme de Lencquesaing’s subtitle is From Bordeaux to South Africa – meaning, more specifically, from Château Pichon-Longueville Comtesse de Lalande in Pauillac (which she inherited in 1978) to Glenelly in Stellenbosch (which she bought in 2003 and established as a fine wine producer). A journey with quite a number of diverse stops on the way, especially pursuing family business interests in places like the Philippines and accompanying her husband, a senior officer in the French Army, from Algeria to the American midwest and elsewhere and back home.

The book is rather charmingly divided into the four seasons. Spring is largely for May’s childhood and youth in the landowning haute bourgeoisie of Bordeaux (we’re told rather a lot about the history of the families of her parents), a period which seems to have been governed by a firm Catholicism and a repressive father who shared with the Church clear and hidebound ideas about the role of girls and women. Not that May complains. She seems to have accepted traditional ideas of family, church and state (with class always implicit), and there’s no indication in the book that she ever challenged them meaningfully – though her own splendid career in the world of Bordeaux wine was itself a pretty fundamental affront to patriarchal ideas about female limitations, and, while her social involvement seems to have been largely seigneurial, it was done with generosity and concern.

Spring takes us to the end of the war, and concludes with an extraordinary report of her marriage in 1948 – extraordinary, that is, in its blandness (something which characterises most of her brief accounts of personal and emotional life). She’d met the man in question just twice, and tells us nothing of even whether she liked him. This is what followed, she says without comment: “my father announced that Captain de Lenquesaing had asked for my hand, and that he had accepted in my stead! They had already set the wedding date for the following month….” That’s it. C’est ça. There’s a lengthy account of her husband’s aristocratic background – perhaps that suffices. Later in the book, after his rising in the military hierarchy, and his clearly playing a significant role in Pichon business, May refers to him as “the General” probably more often than as “my husband” or “Hervé”. (It may be a depressing French thing – apparently Madame herself is widely known in Bordeaux as “La Générale.) His final disease and death came in 1990 – “a difficult and distressing year”, but after “the General lost his final battle”, again, that’s that: “I returned to Pichon soon after the funeral”, writes May calmly, where the vintage “promised to be sumptuous”.

Summer, therefore, is about the different military posts, having children, etc – with rather overlong accounts of the armed conflict between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front, and of various historical moments in the Phillipines (where May’s mother’s family had been rich businesspeople).

It’s with the onset of Autumn that the book starts to get more interesting for those wanting to hear about May’s stewardship of Pichon Lalande and about modern Bordeaux in general. Again, there’s a loud silence about family stuff. We are left to infer that there was a significant family squabble after the death of May’s father. Thanks to an intractable mother, the family assets had been “stuck” for 20 years. Then May and her brother and sister, having sorted out the mother (I don’t think any one of the three is mentioned ever again), drew lots for three chunks of property, and May got Pichon – or, rather, the majority share in the investment company that owned it. “And so, my life once again took a new and unexpected direction.”

In fact, it was a nicely timed shift. Bordeaux was pulling itself together and about to enter a decade of splendid vintages and a whole new relationship to the market, with America now a vital player. The description of these developments, and of the development of the Pichon domaine, still showing the effects of the war and of presumably inadequate management, with major investments under the new director’s guidance furthering its fine reputation, must be fascinating to those with an interest in Bordeaux – and in the growth of the international fine wine market that we know and possibly love.

Along with that of her domaine, May’s personal reputation, as ambassador for Pichon and the Médoc as a whole, grew immensely. Her book is replete with accounts of dealings with the rich, famous and influential in the international wine world. Many important tokens of recognition came. But the accounts of magnificent tastings, grand dinners, dealings with the smarter kind of auctioneer and critic, and relentless lists of great wines (plus tasting notes), are wearying, to me at least. They are, though, probably here more to be put on record in one place than intended to educate or entertain.

Thus Autumn, which also included the flowering of May’s splendid collection of glass and – another dubious lengthy excursion – a potted history of the medium. Winter inevitably followed, and, as we know, it was marked for May by the sale of Pichon (and Ch Bernadotte, acquired in 1997), and the purchase of an orchard estate in Stellenbosch and the establishment of Glenelly Estate in 2003, when May was a remarkably vital 78. There’s an accompanying short history of post-settler South Africa, and a longer one of the Huguenot settlers in the late 17th century. Too-extravagant claims are made for their influence on Cape wine “as seasoned wine-growers”. Cabernets sauvignon and franc, merlot and petit verdot were emphatically not “introduced in the past by the Huguenots”. Historical mistakes apart, the account of the birth and development of Glenelly, and of May’s sympathetic and constructive confrontation with the social realities of rural South Africa, is indeed worth reading. And of course, there’s the building of a fine new collection of art glass to find a home there.

I must add a note on the translation (published by Glenelly, and available from there online for R385), because I suspect that the book might read better in the original French. I haven’t looked at that, but there are too many obvious awkwardness in the English for me to imagine it’s a job well done. “Grandiose” is not a suitable word for a landscape, however impressive it may be; “castle” is very seldom a good translation for château (it doesn’t need a translation anyway, nor does Madame need to be rendered as Mrs); few domestic servants are “nannies”; “second great growth” is not how deuxième cru should be rendered in English – second growth is enough. Decent English prose does not allow for the generous scattering of exclamation marks present in this book. Etc.

The title of the original version of My Journey with Wine was Les vendanges d’un destin (The Harvest of a Destiny), which is rather more poetic and therefore, perhaps, less appropriate, as this is a pretty businesslike book. There was, though, a passage which moved me, and reminded me that perhaps May’s tale is heavily influenced by a private reticence protected behind a public career. She’s speaking of the need to “give a full and accurate account of the life of a wine-making estate”, including the failures and pitfalls, and writes that “the visible takes precedence over what goes on behind the scenes, the anguish, sleepless nights, vulnerability, fragility, solitude”. A touch more of that evidence of sensibility throughout would have made for a warmer effect in what is offered as a memoir.

Madame de Lencquesaing turned 100 last Saturday and celebrated her centenary at Glenelly. She’s made a difference to Cape wine in her years here, and it’s been a good difference; we must congratulate her, and wish her more years of health and involvement.

Win a set of four tickets (worth R450 each) to Wine Concept’s fifth annual Grape Escape Wine Festival.

Win a set of four tickets (worth R450 each) to Wine Concept’s fifth annual Grape Escape Wine Festival.

Date: Thursday, 29 May 2025

Time: 18h00 to 21h00

Venue: Moyo Restaurant, Kirstenbosch, Cape Town

The festival, themed “Escape from the Norm,” showcases uncommon varieties and blends from 40 of the country’s top wine producers. All featured wines will be available to order at special discounted prices from Wine Concepts on the night.

To enter, simply sign up for our free email newsletter – click HERE.

Purchase tickets via Quicket online HERE.

Competition not open to those under 18 years of age and closes at 17h00 on Friday 23 May. The winner will be chosen by lucky draw and notified by email. Existing subscribers are also eligible.

Regular readers of this column will know that I am a firm proponent of regular exercise as part of a healthy lifestyle. At the same time, it is well documented, that alcohol misuse can lead to significant muscle loss. Does it therefore follow, that moderate wine consumption and a recreational exercise program are mutually exclusive?

On this occasion, I will look at resistance training, which trains muscle power and builds muscle bulk as opposed to cardiovascular (endurance) training, which will be commented on in a forthcoming column. Resistance exercise leads to a certain level of muscle damage which may be ameliorated by anti-oxidants but also needs to be repaired. Wine contains two components that are important in muscle metabolism: Alcohol and anti-oxidants in the form of polyphenols such as resveratrol but also tannins and anthocyanins. The scientific evidence is that moderate alcohol consumption does not alter general blood parameters relating to muscle metabolism; the list here is quite exhaustive and includes simple measures such as: Creatine kinase, a measure of muscle damage; lactate as a measure of anaerobic stress; hormones such as cortisol, a general stress hormone; testosterone and estradiol, both a measure of metabolism status; inflammatory parameters such as c-reactive protein, leukocytes and cytokines.

As for more complex, direct measures of muscle metabolism, one can only salute the heroism of a group of Australian athletes. These intrepid individuals suffered in the name of science for a detailed study of muscle metabolism in recovery after strenuous leg exercise followed by the consumption of defined chemical mixtures: A protein solution, a protein and alcohol solution and a carbohydrate and alcohol solution. The fluids were consumed immediately after and again 4 hours after exercise. Muscle biopsies were taken from their legs at rest, at two and eight hours after exercise for a detailed study of muscle metabolism.

Just imagine, having your muscle biopsied, then exercising hard and having to drink (for the alcohol assigned part of the trial) the equivalent of one bottle of wine in one go and have your already sore muscles biopsied twice more! At least now we know that indeed after a protein drink without alcohol muscle recovery metabolism is most active, followed by the alcohol-protein drink and lastly by the alcohol-carbohydrate drink. Differences were significant, but not large. Does this then also reflect in practical measures of muscle performance? In an exhaustive review of alcohol consumption and recovery after resistance exercise no differences were found in muscle power, force, endurance and soreness.

Is it then right to speculate that the anti-oxidants in wine may help with training? I am not aware of any studies on wine in particular and it would anyway be difficult to separate the effects of the anti-oxidant polyphenols from the effects of alcohol. There are, however, a number of studies which have assessed anti-oxidants (such as Vitamins E or C or resveratrol, a wine polyphenol) as such given before exercise. Again, there is little evidence, that these achieve anything in an exercise program other than a minor decrease in perceived muscle soreness. A caveat here is that that the anti-oxidants were given in high dosages and in these dosages may actually impair certain mechanisms by which muscles recover after exercise.

So, it is safe to conclude that moderate wine consumption does not interfere with nor enhance a resistance exercise program and so both have their rightful place in a healthy lifestyle. One should, however, better not drink a bottle of wine immediately after exercise. But what is the best sequence? Ever wondered why your neighborhood sports club is fullest early in the morning? Indeed, the human body’s biorhythm is tuned for exercise in the morning with stress hormone levels peaking at about 4 a.m. The best time for exercise therefore is early morning. Conversely, the best time to enjoy your daily glass of wine is in the evening, when the health club is empty and the local wine bar full. Cheers to that!

I mulled for over a month on how best to respond to Christian Eedes’s editorial published on 17 March and headed “The Great Divide – Cape Town vs. Johannesburg market realities”. There was much to what he said which could be regarded as factual. “…it can feel occasionally that we’re preaching to the converted. Looking at our users by city for the last 12 months, Cape Town makes up 31% and the entire Gauteng region 20%. It’s even more of an issue for many boutique wineries, Gauteng – South Africa’s economic heartland – remains a distant, largely untapped market….This raises important questions: Is the divide between the two regions driven by demand, logistics, or perhaps cultural and socio-economic factors?”

Unfortunately there was also comment which at best reflected the divide and, at worst, was simply ill-informed and parochial. Perhaps the most offensive – or perhaps the most controversial – was “Despite Johannesburg’s high disposable income, wine culture in the city lags far behind that of Cape Town” though the following comes a close second: “While Cape Town’s wine culture is more about mindful appreciation, Johannesburg tends to favour conspicuous consumption, where status is often displayed through visible wealth, such as expensive cars, clothes, and lavish lifestyles.”

I’m curious to know where (that is, from which digit or orifice) our esteemed editor sourced that information. I suspect he’s spent more time in Europe in the past year than in Johannesburg. I’m not sure he’s ever been to WineX, an event which sees over 8 000 wine enthusiasts at the Sandton Convention Centre every year. This is an audience the vast majority of whom are black, middle class and not necessarily quaffing Moët, or Clicquot or Johnnie Walker as their everyday beverage of choice.

Of course, to every caricature there is at least a grain of truth. Johannesburg probably has a higher density of tenderpreneurs than anywhere else in SA. Naturally (so the logic goes) all wine consumers in the City of Gold “favour conspicuous consumption…expensive cars, clothes and lavish lifestyles.”

The comments which followed his article do not appear to have emanated from wine drinkers in Johannesburg (perhaps because, as the editor himself noted, there are relatively fewer Winemag readers in Johannesburg). One of those who did comment focused rightly on the issue referred to in the main piece – the logistical challenges of doing business at a distance, especially if you are a hipster winery with a ready market for your small production less than two hours drive from your cellar.

If you are a boutique producer based in Paarl, Elgin or the Swartland you don’t need to employ the services of a distributor. Nor do you need to surrender around 30% of your revenue for sales and logistical support. And you can develop a rapport with the folk who draft the wine-lists in the Mother City. So in a way this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. No one knows who you are outside of the circle of your acquaintance – and the cost of widening that circle is prohibitive, relative to the volumes you produce.

Once every five or ten years an Eben Sadie or Chris Alheit comes along and escapes the gravitational field of the Cape’s boutique-model death-star. David Clarke at Ex Animo (whose sales director is actually Christian Eedes’s wife, a material disclosure usually missing in all the plugs which promote Ex Animo wines on the Winemag website) has done a great deal to make things easier for hipster producers: slowly more and more of the brands he represents are starting to appear on wine lists in Gauteng. How they are doing this is central to the discussion. They are engaging with the trade in exactly the same way that they have been in the Cape: their wines are being “talked” into the establishments by the producer who personally engages with the wine service team and/or the proprietor.

Once wine is properly made – in other words, without visible defects – from quality fruit sourced from a site capable of yielding a wine of some complexity, the most important message is the backstory. This involves both the category itself and the face behind the brand. Older appellations – Bordeaux or Champagne – depend more on the brand message of the category as a whole; more modern ones depend both on the personality of category (the Swartland is geeky in the way that the Medoc is aristocratic and traditional) as well as the individual behind the brand (Antinori or Sadie, for example). It is because the young hipster winemakers are working the Cape market so assiduously that they have done so well there. It is not because, as Eedes asserted in his column “Cape Town’s wine culture is more about mindful appreciation, Johannesburg tends to favour conspicuous consumption”

Finally, there is I think a much more obvious reason why smaller Cape producers battle to gain traction in Gauteng. It’s the same reason that, for example, the London market is harder to crack for producers everywhere than say San Francisco is for Californian winemakers. It has no loyalty to any one appellation. Much of the wine sold in Cape Town’s restaurants goes to the huge tourist traffic which descends on the city for the summer. Visitors to a wine region want to drink the wines produced there and they are dependent on the sommeliers who work in the restaurants for guidance. It pays hipster winemakers to invest time in them, to chat them up, to supply them with the motivations they will need to on-sell the wines.

Gauteng is a market with only a passing loyalty to the Cape. It’s even possible to argue that given the political divide separating the two administrations there isn’t an automatic affinity. If the Cape’s winemakers want to see their treasures on Gauteng’s wine lists, they could start by “kuiering” a little.