Much to like about the Fairydust Field Blend 2023 from Ken Forrester. The packaging won gold at this year’s Label Design Awards and what’s inside the bottle is pretty smart, too.

Much to like about the Fairydust Field Blend 2023 from Ken Forrester. The packaging won gold at this year’s Label Design Awards and what’s inside the bottle is pretty smart, too.

From a Piekenierskloof vineyard planted in the early 1960s consisting of Chenin Blanc and Palamino, the nose shows lime, cut apple and fynbos while the palate is dense, broad and thick textured despite a moderate alcohol of 13%. Acidity, meanwhile, seems moderate, the finish gently savoury, perhaps slightly salty. A wine with plenty of interest.

CE’s rating: 92/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

De Kleine Wijn Koöp label belongs to winemaker Wynand Grobler and wife Anya, with them operating out of a small cellar in the heart of Paarl, grapes sourced from across the winelands.

De Kleine Wijn Koöp label belongs to winemaker Wynand Grobler and wife Anya, with them operating out of a small cellar in the heart of Paarl, grapes sourced from across the winelands.

Grapes for the Hoendertande Grenache 2022 (R300 a bottle) come from a Piekenierskloof vineyard planted in 1972, winemaking involving whole-bunch fermentation before maturation in 500-litre barrels. The nose shows attractive aromatics of red berries, orange and musk plus hints of cured meat, truffle and spice. The palate is rich and broad, bright acidity lending a counterpoint, the tannins soft and powdery. Alc: 14%.

CE’s rating: 92/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

What better to sit tasting wine on the veranda of Stellenbosch biodynamic farm Longridge situated at the foot of the Helderberg looking back towards Table Mountain? The one proviso is that the top-end wines don’t come cheap but they are good. Tasting notes and ratings for the new releases as follows:

Clos du Ciel Chardonnay 2022

Price: R800

From a 1.5ha block planted to nine different clones in 1987. Matured for 12 months in barrel, 50% new. Lemon, grapefruit, oatmeal, nuts and some struck-match reduction. Concentrated fruit and fresh acidity before a pithy finish. Substantial and textured but equally vital. Alc: 13%.

CE’s rating: 95/100.

Ekliptika 2020

Price: R630

39% Cabernet Franc, the rest Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Petit Verdot. Red and black berries plus subtle notes of floral perfume, herbs and pencil shavings. The palate is refined rather than elegant – generous fruit, fresh acidity and fine tannins, the finish gently savoury. Already quite open but should mature gracefully over the medium term. Alc: 14.5%.

CE’s rating: 94/100.

Maandans Pinotage 2020

Maandans Pinotage 2020

Price: R1,320

Grapes from a vineyard planted in 1972. Matured for 18 months in barrel, 50% new. Enticing aromatics of red cherry, cranberry, rose, a hint of mint and other herbs. Lovely clarity of fruit, zesty acidity and fine tannins, the finish long and dry. Poised and intricate, it’s 14.5% alcohol impossible to discern.

CE’s rating: 95/100.

Misterie Merlot 2019

Price: R2,130

Matured for 24 months in barrel, 80% new. Red berries, tomato cocktail, potpourri, vanilla, chocolate and pencil shavings on the nose. The palate is medium bodied with fresh acidity and velvety tannins. Plush but not heavy or sweet. Alc: 14%.

CE’s rating: 93/100.

Longridge Ou Steen Chenin Blanc 2023 (R520 a bottle) rated 94 in April this year – see here.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

As the chill winter winds of discontent continue to blow across much of the world’s fine wine markets, many fine wine merchants are taking advantage of the more subdued trading conditions to travel to Burgundy to taste and assess the upcoming 2023 vintage red and white wines in barrel. I also recently returned after extensive domaine tastings in Burgundy, having accompanied another market-leading UK Burgundy merchant, and was fascinated to hear all the trials and tribulations the growers have been subjected to in the past year – some of them market related, but mostly weather related in 2024.

While the 2022s, tasted in Burgundy in November 2023 and proposed to the UK trade and private clients in London in January 2024, were mostly exceptional wines from an increasingly lauded vintage for reds as well as whites, the prospect of another plentiful, above average quantity vintage in 2023, presents its own set of unique challenges, coming at a time when many of the market’s leading merchants and importers are still holding sizable quantities of unsold stocks from both the low yielding 2021 harvest as well as stocks from the average to plentiful 2022 vintage.

But what can we expect from the 2023 Burgundy vintage? Well, for starters it’s a big harvest with some growers seeing yields up 10% to 30% on 2022’s quantities, which were considered “normal to good” in most appellations. So, the yields are abundant, but what about the quality? Chardonnay, overall, tends to perform better at higher yields than Pinot Noir, and this supports the growing school of thought that 2023 is perhaps more promising in white than in red. Nevertheless, 2023 is a more charming, elegant and accessible vintage across the board than the denser, more powerful 2022s, but also a finer, more ethereal, cerebral expression of Pinot Noir.

Many of the reds, whether petit Village wines, Premier Cru or Grand Cru wines, showed pretty, light-touch structures with sweet strawberry-tinged fruits, fresh juicy acids, and soft, silky, supple tannins that convey the overall higher yielding fruit feel of the vintage in general. In other words, mostly earlier drinking wines with great youthful fruit forward appeal. However, who would ever have thought that higher yields, loose knit structures and generous juicy fruit profiles could harbour problems for growers and merchants?

Don’t get me wrong. I am normally all over the bright fruits, the crystalline acids and soft, easy-drinking accessibility in some Burgundy reds, but perhaps a little less enthusiastically so when you are tasting a big name domaine Premier Cru Vosne Romanée, Gevrey Chambertin or a Grand Cru Echezeaux that tastes eminently ready to drink from barrel, yet lacking the essential tension of great Burgundy… and you also know it’s going to cost you €150, €250, or €400+ Euros per bottle ex-cellar! Ironically, the sheer accessibility and youthful drinkability of the 2023 vintage could be the biggest proverbial thorn in its side when it comes to offering the wines En-primeur, especially at a time when the market’s merchants and its fine wine consumers are looking seriously overstocked.

While not exactly a silver lining, the fact that most wine producers across Burgundy, and indeed the whole of France, experienced yields on average down by 70% in 2024 due to terrible flowering and incessant rain through the season causing endless disease pressures, will somewhat mitigate the large surge of stock that is about to be offered to the market. In Bordeaux, you can argue that their price escalator has been primed to drop down to the basement, and their prices should in all likelihood see significant reductions come En-primeur time in April / May 2025 if quality is anything to go by.

However, in Burgundy, with the prices of grapes so closely tied to the value of the land, whether rented on a fermage basis, or whether owned and fruit is merely sold off as grapes or juice to other growers and negociants, there is less headroom to drop prices, not to mention much less inclination on behalf of growers after a decade of boom times where demand consistently outstripped supply globally. Add to this the complete and utter collapse of the Asian, and Chinese wine market in particular, and you start to see the growing causes of anxiety among many producers.

But perhaps with more philosophical relevance for South African producers, after listening to all the market challenges Burgundian producers are now facing or are about to encounter, it bares considering some of the many clear miscalculations numerous Burgundian domaines committed during the plentiful times of the past decade, so that other producers might be less inclined to let history repeat itself by falling into the same traps.

Here are my top five takeaways after analysing Burgundies coming woes:

1 Always remember who your core clients are.

This is probably the number one schoolboy error producers make when times are buoyant, demand is high, money is loose and plentiful, and incoming requests from newly established markets like Asia or China specifically, cause producers to become a bit greedy, forgetting their long-established clientele and their market needs. It’s a mistake. Loyalty should always be considered and rewarded.

2 Price your wines for slow long-term growth not quick short-term gain.

Quite clearly, this is a wide ranging and complicated economic scenario, nevertheless, most Burgundian producers have become victim of their own success, looking to avoid secondary market speculation by incessantly increasing the price at source to directly benefit from strong global demand, thereby reducing the wines drinkability and further increasing global speculation.

If we cast our minds back to Bordeaux in the noughties, their colossal price increases were largely driven by the chateaux getting sick and tired of seeing brokers and traders making all the money on the highly speculative secondary market, and so they raised their price at source and ‘sucked all the life out the market’, ultimately leading to several mini-price crashes at the worse, or stagnation and plentiful product available on the market 24-36 months after En-primeur at -15% to -20% below release prices at best.

3 Always allocate stock to your oldest and most loyal markets first.

When it comes to managing finite stocks of high-demand wines, always make sure that your older, more established markets receive enough stock to satisfy demand. Preferably, this should be done through an established agent or merchant network rather than through more cloudy broking channels. If you persist in giving a market, like for example, Spain or Portugal, unrealistically high allocations, don’t be surprised when you find all this stock being flipped and ending up in the UK via the grey market, there the real private client wealth and demand normally lies.

4 Don’t follow foolish fashions or trends, follow what works for your own brands long-term future.

I will refrain from naming specific brands or producers, but the past couple of years have seen far too many Burgundy wines suffering from the “emperor’s new clothes” syndrome. €300 negociant Aligote with pretty labels is never going to be a long-term market proposition. It’s a bubble looking to pop before the label glue is dry on the bottle. And of course, pop it did.

5 Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Lastly, it’s economics 101. Don’t commit all your allocations, resources and marketing expenditure to any one single market like so many producers have done with China at the expense of more traditional markets like the USA, the UK, and Canada. When the wind turns and business dries up, like it has now, the old traditional markets will be far less forgiving than they perhaps would have once been years ago. Spread your allocations and spread your love, then tweak as and where is required to achieve a good, broad, balanced regional distribution coverage.

In the same way that wine consumers often revert to the safety and comfort of more traditional, classical wine brands in tougher economic times at the expense of new-wave, Johnny-come-lately labels, so producers should perhaps act now with a little more caution, circumspection and restraint when deciding their wider global business, pricing and distribution strategies. Customer loyalty is hard to earn but very easily lost in this new global era of fine wine.

This year’s Rosé Report convened by Winemag.co.za and sponsored by global financial services company Prescient is now out. There were 44 entries from 39 producers and these were tasted blind (labels out of sight) by a three-person panel, scoring done according to the 100-point quality scale.

The 10 best wines overall are as follows:

Quoin Rock 2024

Price: R165

Wine of Origin: Simonsberg-Stellenbosch

Abv: 13.13%

Vriesenhof 2023

Price: R125

Wine of Origin: Stellenbosch

Abv: 12.17%

Warwick The First Lady Dry 2024

Price: R115

Wine of Origin: Western Cape

Abv: 11.5%

Durbanville Hills Merlot 2024

Price: R90

Wine of Origin: Durbanville, Cape Town

Abv: 13.63%

Meraki Grenache 2024

Price: R95

Wine of Origin: 12.88%

Abv: Coastal Region

Van Loveren Daydream Chardonnay Pinot Noir 2024

Price: R69

Wine of Origin: 12.15%

Abv: 12.15%

Vinevenom Shining No. 3 NV

Price: R190

Wine of Origin: Swartland

Abv: 13.4%

Vriesenhof 2024

Price: R125

Wine of Origin: Stellenbosch

Abv: 12.25%

Zorgvliet Cabernet Franc 2024

Price: R130

Wine of Origin: Banghoek

Abv: 13.75%

Tokara 2024

Price: R115

Wine of Origin: Western Cape

Abv: 12.5%

Rosé refers to wines coloured any shade of pink from hardly perceptible to pale red. There are many ways to make rosé wines but the most common technique is a short maceration of the juice with the skins of dark coloured grapes just after crushing for a period just long enough to extract the required amount of colour.

In France, rosés are particularly common in warmer, southern regions where there is local demand for a dry wine refreshing enough to drink on a hot summer’s day but still bears some relation to red wine. Provence in the far southeast of the country is the region most famous for its rosé, Bandol the most prestigious appellation.

The average price of the 18 wines to rate 90-plus is R115 a bottle and of the Top 10 is R122.

To read the report in full, including key findings, tasting notes for the top wines, buying guide (wines ranked by quality relative to price) and scores on the 100-point quality scale for all wines entered, download the following: Prescient Rosé Report 2024

According to a post by Wine Business Advisors on X, Van Loveren has acquired the majority share in Neil Ellis Wines, the deal finalised on 1 December.

Neil Ellis was the first local winemaker to work as a serious negociant in the 1980s. In 1993, Ellis and businessman Hans Peter Schröder, who had acquired Jonkershoek property Oude Nektar, formed the partnership Neil Ellis Wines, the venture later moving to its present location on the lower reaches of the Helshoogte Pass. Warren, Neil’s son, is the current winemaker.

Van Loveren, the family-owned wine company with its origins in Robertson, also recently acquired the Survivor Wines brand from Overhex – see here. Origin Wine, meanwhile, have recently acquired the rest of the brand portfolio previously owned by Overhex (Balance Wines, Get Lost Wines, Mensa Wines, The Mooring Wines, and others).

Stellenbosch property Blaauwklippen announced at the end of last month that it was taking back full control of its wine production, distribution, and marketing operations after a 30-month partnership with Van Loveren.

Jasper Raats of Stellenbosch property Longridge also makes wine under his own label. He made a name for himself making Pinot Noir in Malborough, New Zealand earlier in his career and is now intent of showing that he can make top-end wines from a carefully selected site in Stellenbosch. Tasting notes and ratings for the current releases:

Cuvée Rika Pinot Noir 2022

Price: R315

Grapes from a Helderberg block planted in 2014. Matured for some 15 months in barrel, 10% new. Heady aromatics of red and black cherry, musk, cured meat and spice. Good fruit concentration, bright acidity and nicely grippy tannins – not as slight as cooler climate examples can be. Alc: 13.7%.

CE’s rating: 93/100.

Cuvée Rika Reserve 2021

Cuvée Rika Reserve 2021

Price: R650

Made with the intention of achieving the most intense, full-bodied example of the variety possible. Inky in colour. Black cherry, incense, cured meat, earth and spice on the nose. The palate is potent – dense fruit, bright acidity and firm tannins, the finish long and deeply savoury. An emphatic counter to those who believe Pinot should always be light and sprightly… Alc: 14.5%.

CE’s rating: 92/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

Wine Cellar, the fine wine merchants and cellarers based in Cape Town, recently hosted a vertical tasting Magentic North, one of the pinnacle examples of Chenin Blanc in the Alheit Vineyards range. Grapes come from two unirrigated, ungrafted parcels one planted in 1984, the other in 1981 on Citrusdal Mountain (Skurfberg) at 520 meters above sea level. Planted on iron-rich sandy soil over clay, they comprise about 2.8ha together and give minute yields.

The tasting was presented in three flights of four wines. Those that were present knew that every vintage yet produced was included and that they were tasting in consecutive order from oldest to youngest. However, two mystery wines were also part of the line-up and the tasting would be conducted blind. My notes and ratings as follows:

Radio Lazarus 2012

Rating: 95.

Not originally rated.

Maiden vintage of this wine from a Bottelary vineyard. The nose shows some pleasing evolution with notes of bee’s wax and honey but also pear, peach and fynbos. The palate is rich and broad with well-integrated acidity. Layers of flavour and still very satisfying to drink.

Magnetic North 2013

Rating: 93.

Original rating: 96 – July 2014.

Peach and apricot but also significant advancement – oatmeal plus nutty, yeasty notes. Full and intensely savoury finish. Drink up.

Magnetic North 2014

Rating: 96.

Original rating: 96 – May 2015.

Lime, lemon, peach and struck-match reduction on the nose. Pure fruit and bright acidity before a finish that’s pithy and extraordinarily long. Great precision and energy.

Magnetic North 2015

Rating: 94.

Original rating: 96 – July 2015.

Exotic aromatics of melon, pineapple and some wet wool. Sweet, rich and round, tangy acidity lending life, some bitterness to the finish. Characterful but probably at its peak.

Magnetic North 2016

Rating: 94.

Original rating: 96 – May 2017.

Stone fruit, cut apple and honey plus yeasty, leesy notes on the nose. The palate is dense and thick textured with coated acidity. Some debate about whether this bottle showed signs of premature oxidation due to closure failure.

Magnetic North 2017

Rating: 97.

Original rating: 96 – June 2018.

Beguiling aromatics of pear, peach, citrus, mint and fynbos plus wet wool. The palate is all about controlled power – great concentration and punchy acidity before a dry finish. Time in bottle has only served this wine well.

Magnetic North 2018

Rating: 96.

Original rating: 98 – August 2019

Lime, green apple, white peach, fynbos and some flinty reduction on the nose while the palate shows pure fruit, electric acidity and a pithy finish. A lighter vintage holding well.

Magnetic North 2019

Rating: 98.

Original rating: 97 – July 2020.

Gorgeous aromatics of white, green and yellow fruit plus fynbos. The palate is vivid and elegant. Lovely fruit expression, the finish lightly grippy. Poised and so very detailed, a classic example of old-vine Chenin Blanc.

Magnetic North 2020

Rating: 95.

Original rating: 96 – August 2021.

Exotic aromatics of melon, blue orange, grass and herbs. The palate is substantial – broad and open with fresh acidity and a savour finish. Not as tightly wound as either 2017 or 2019 and hence destined for earlier drinking.

Magnetic North 2021 never released due to equipment failure.

Gone South 2022

Rating: 98.

Original rating: 98 – October 2023.

Super-intricate aromatics of pear, peach, citrus and fynbos while the palate shows weightless intensity and plenty of energy. Chris Alheit declassified this vintage but this again seems to have been an excessively cautious decision.

Sadie Ouwingerdreeks Skurfberg 2022

Rating: 96.

Original rating: 93 – August 2023.

The nose is very pretty with notes of flowers, herbs, pear, peach and lime while the palate is light bodied with fresh acidity and a pithy finish. On release, I noted the alcohol as being lower than usual (13.08%) and remarked that it appeared “a little incomplete and lacking in detail – time in bottle will be revealing” and it seems to be on an upward trajectory.

Magnetic North 2023

Rating 98 in June 2024 – see here. It’s pedigree plain to see but in the context of this tasting almost ridiculously primary.

Some general observations When do South African white wines provide optimal drinking is a question that gets asked perennially, and based on this tasting, my answer would be five to seven years from vintage, the 2017 and 2019 currently in great shape, no longer entirely primary but leaving the drinker imagining what greater interest they might still provide rather than in decline and providing you with a wistful feeling as to former glories now past. One proviso here is, of course, that some have a greater tolerance for developed characters, and if very tertiary aromas and flavours are what turn you on, then feel free to age your wine longer. The other qualification to make is that there will always be exceptions to the general rule – the good showing of the 2014, a somewhat unheralded vintage, was a pleasant surprise.

The converse to the above is that drinking truly great modern-era wines like Magnetic North too early, which is to say on release or within three years of vintage, is to miss out on a large part of the pleasure that these wines can provide.

Lastly, while Magnetic North clearly originates comes from a superior site, tasting this line-up gave a sense of both viticulture and winemaking becoming more precise and refined over time, vintage variation notwithstanding. Closure, inevitably, is also a factor in how these wines mature – the shift from natural to technical cork that Alheit undertook from 2018 appears to be serving Magnetic North well.

Mark Wraith and family acquired two adjacent farms between the Helderberg and Stellenbosch Mountain to form Keermont in 2003, Alex Starey starting as viticulturist and winemaker in 2005, roles he continues to hold to this day. Wines are released on a rolling basis, tasting notes and ratings for some of the latest cuvées as follows:

Terrasse 2023

Price: R290

46% Chenin Blanc, 15% Chardonnay, 15% Sauvignon Blanc, 12% Viognier, 10% Roussanne, 2% Marsanne. Matured for 12 months in older oak. Flowers, fennel and other herbs, lime and peach on the nose. Good fruit concentration and vibrant acidity before a super-dry finish. Not exactly lean, this vintage nevertheless has a nice tension about it. Alc: 13.5%.

CE’s rating: 95/100.

4 Barrels Rosé 2024

Price: R215

75% Mourvèdre, 25% Shiraz. Matured for six months in older oak. Watermelon, red apple, potpourri, earth and spice on the nose. Good weight and smooth textured, the acidity well integrated, the finish gently savoury. Flavourful, rich and round. Alc: 14%.

CE’s rating: 91/100.

Merlot 2021

Release: March 2025.

89% Merlot, 8% Malbec, 3% Cabernet Franc. Matured for 20 months in older oak. The nose shows a top note of rose before red and black berries, dried herbs and earth. The palate is medium bodied and well balanced – good freshness and firm but not coarse tannins. Alc: 14%.

CE’s rating: 92/100.

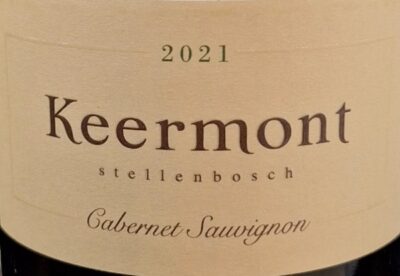

Cabernet Sauvignon 2021

Cabernet Sauvignon 2021

Price: R400

95% Cabernet Sauvignon. 5% Cabernet Franc. Matured for 21 months in older oak. Cranberry, cassis, crushed leaves and violets on the nose. The palate is full but balanced and fruit driven in the best sense. Classically styled with lively acidity and nicely grippy, food-friendly tannins. Alc: 14.5%.

CE’s rating: 93/100.

Fleurfontein 2023

Price: R345 (375ml bottle)

From Sauvignon Blanc. Stems pinched with pliers, grapes left to dry on the vine for four weeks. Matured in French and Hungarian oak barrels for 15 months. The nose shows dried apricot and honey while the palate is luscious, dense and creamy. Entirely decadent! Alc: 12%.

CE’s rating: 92/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

Last week I was fortunate enough to attend a cork versus screwcap tasting in London, held by Stephen Browett of Farr Vintners, one of the top fine wine brokers and retailers in the UK. He’d managed to get together 25 mature wines bottled under both cork and screwcrap so we could taste them side by side blind. It was a very interesting exercise and the gathered tasters, all of whom have considerable experience with wines of all styles, voted on their favourites. Two take-homes: one was that even experienced tasters disagree; and, two, the results were all over the place. For some wines, screwcap was vastly preferred, while for others sometimes the cork-sealed wine won. It’s complicated.

There’s a further issue here. The screwcap is not the closure. It’s just a means of holding a liner or wadding in contact with the neck of the bottle, and this is what seals the wine. It’s the properties of the liner that determine how much oxygen it lets in (the oxygen transmission rate, known as OTR for short). For almost all screwcapped wines a liner called saran/tin, with a metal layer in it, is used. This has an OTR of almost zero. For some wines, a Saranex-only liner is used, which allows a bit more. Many of the screwcapped wines in the comparative tasting were sealed with a Saranex liner. You can tell the difference because these liners are white, and the saran/tin ones are shiny metallic in appearance: look inside the cap.

A further matter in question is that in many of the cork-sealed bottle, a closure called Diam was used. This is a technical closure made of small granules of cork, cleaned from taint, and then glued together. These come in three main types: Diams 5, 10 and 30, offering a lower OTR seal as the number goes up. Cork itself shows natural variability in terms of OTR. Immediately we see this is a hugely contentious topic.

Let’s backtrack. How did we get here? There was a time when all wines were sealed with cork. Alternatives were tried in Australia in the early to mid-1970s (screwcaps with a range of different liners, including cork, but these never took off), in Switzerland screwcaps became popular in the 1970s onwards for whites, and then in the mid-1990s plastic corks began to be used in Australia and California. The motivation for alternatives was cork taint: the musty defect from fungal-derived molecules in the cork. By the end of the 1990s these taint rates had grown, apparently because more wines were being bottled and this was putting pressure on the cork sources in Portugal and Spain. The Australians and New Zealanders were being sent some awful corks, and so the move to screwcaps, after some trials in 1998 and 1999, followed by 14 Clare Valley producers moving to screwcap together with the 2000 vintage, was rapid. Before long, almost all wines in Australia and New Zealand were being screwcapped.

Plastic corks turned out to be problematic. The injection-moulded models did a good job of keeping wine in, and were taint-free. But people soon found out that plastic allows oxygen to diffuse through it, and so the wines soon began to oxidize. Newer versions that were based on extrusion were a bit better, but still had the problem of high oxygen transmission. So it turned out that it’s the screwcap that became the true alternative to cork.

With the alternative closures, suddenly the lens was turned on post-bottling wine chemistry. A famous comparative closure study from the Australian Wine Research Institute compared a range of closures with the same wine (a 1999 Clare Valley Semillon) over a five-year period. Among other things, they concluded that if you use a closure with a different level of OTR, from that moment on, you have a different wine. Wines develop differently under different closures. Some of the wines sealed with a tin/saran-lined screwcap began to develop subtle reductive notes, because the volatile sulfur compounds in the wine were changing form in the absence of any oxygen. The plastic-cork-sealed wines oxidised fast. Overall, the screwcap seemed far the best closure, save for the very subtle reductive notes.

How much OTR do we want from a closure? The answer remains elusive. Studies have shown that a wine sealed hermetically in an ampoule will still develop, but more slowly, and it will develop reductive characters. Reducing OTR doesn’t just slow the development of a wine; that wine ends up going places that other wines won’t. Bottling with more headspace air/oxygen doesn’t avoid reductive characters developing, it just causes some oxidation, and is not the answer. Adding copper to fine the wine isn’t the solution either: it may get rid of some of the reductive issues in the short term, but they can still emerge post-bottling, and there’s a danger of oxidising some good wine components.

But it’s also a myth that corks breathe. The ideal cork behaves similarly to a tin/saran-lined screwcap and lets very little oxygen through. But one thing corks do is that they have oxygen dissolved in them that they release very slowly.

Which is best? Cork or screwcap?

Screwcap has the benefit of being taint free, and also cheap. For many wine styles, this seems to be the ideal closure, and from a consumer and restaurant point of view they are easy to open (although fancy sommeliers may feel deprived of the chance to demonstrate their cork-removal skills). Some markets are happy to pay top dollar for screwcapped wines; others seem insistent that fine wine should be cork-sealed.

Cork has the benefit of pole position: the fine wine world’s icons are cork sealed and there is a rich tradition of ageing wines under cork for many decades, and we like the results. It is also more aesthetic and it’s a natural product. But it is also inconsistent and expensive, and cork taint is still with us. Why should we stick with it? The only answer I have is that some wines taste better when aged under a good cork. Is this proven? Not really, but it’s my experience that wines sealed with different closures taste different, and for some wine styles, the cork really works well. For others, screwcap works better. It is, to reiterate, complicated.

More on the same contentious subject here.