Tim James: The maverick who built Hemel-en-Aarde reconsidered

By Tim James, 6 November 2025

“If you seek his monument, look around you.” So runs the epitaph (in Latin) on architect Christopher Wren’s tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral in London. It could work well as an epitaph for Tim Hamilton Russell in the Hemel-en-Aarde. His establishment of Hamilton Russell Vineyards back in 1975, with not a vineyard in sight, was perhaps foolhardy, but wonderfully far-sighted. Now with vineyards and wineries aplenty – many of them owned by winemakers imprinted, through earlier employment, with the Hamilton Russell DNA – the area’s success is ample vindication of Tim’s, and his advisors’, foresight and struggle: I’m not sure there’s now a Cape wine area of any size with a higher average bottle price, and in this case that’s a good indication of well-earned reputation.

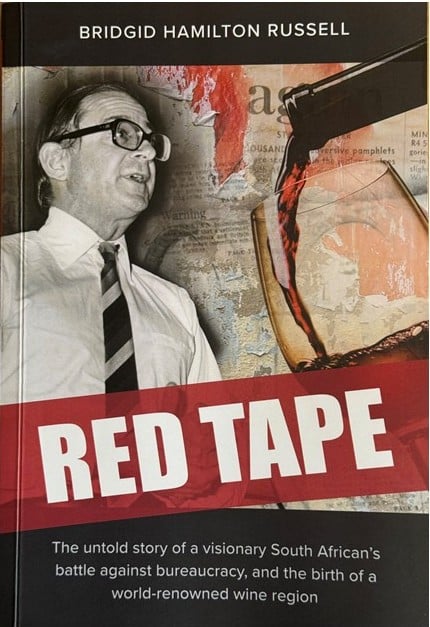

More of that early struggle anon, with reference to a new book by Tim’s daughter Bridgid Hamilton Russell, but note immediately that if the Wrennish epitaph were used for Tim, it would emphatically be in English – most certainly not Afrikaans. I’ll return to that issue too.

Bridgid HR is the daughter of Tim, and sister of the current owner of HRV, Anthony HR, and her book, Red Tape, is somewhat lengthily subtitled “The untold story of a visionary South African’s battle against bureaucracy, and the the birth of a world-renowned wine region”. Actually not entirely untold: Michael Fridjhon’s Penguin Book of South African Wine (1992) has a chapter almost entirely devoted to the story, with many details that serve to usefully supplement the new book – and in parts, I think, even correct it. For example, where Red Tape says that no grapes had ever been planted in the area, Fridjhon says that there had been some pre-phylloxera viticulture there. Fridjhon is, incidentally, generously acknowledged by the author, along with wine-critic and winery-owner John Platter, as good and useful friends to Tim’s efforts, as well as the late Dave Hughes as provider to her of much contextual information.

Bridgid HR is the daughter of Tim, and sister of the current owner of HRV, Anthony HR, and her book, Red Tape, is somewhat lengthily subtitled “The untold story of a visionary South African’s battle against bureaucracy, and the the birth of a world-renowned wine region”. Actually not entirely untold: Michael Fridjhon’s Penguin Book of South African Wine (1992) has a chapter almost entirely devoted to the story, with many details that serve to usefully supplement the new book – and in parts, I think, even correct it. For example, where Red Tape says that no grapes had ever been planted in the area, Fridjhon says that there had been some pre-phylloxera viticulture there. Fridjhon is, incidentally, generously acknowledged by the author, along with wine-critic and winery-owner John Platter, as good and useful friends to Tim’s efforts, as well as the late Dave Hughes as provider to her of much contextual information.

Certainly, when Tim, a wine-loving Johannesburg advertising executive, bought the uncultivated farm Braemar, there were no grapes in the valley. There was, though, curiously and unexplained by either Fridjhon or Bridgid HR, a nearby farm that was in possession of a “quota” – the necessary permit to grow grapes for wine, issued by the KWV on behalf of the state. This was to make all the difference, because it quickly emerged that there was no question of Tim’s getting a quota for Braemar.

Rather strangely and naively, however, as this new book makes clear, Tim seems to have thought that the authorities would be convinced by, and welcome, his ambition to take forward South African wine by growing “noble” grapes and making wine in this comparatively cool climate. But no. Hence the first entanglement in the bureaucratic stubbornness that the title of Red Tape alludes to. So he bought the other farm with the quota, while planting on Braemar the grapes he wanted, aiming to pass off the “illegal” grapes as properly quota-ed. It is, and was, all a bit complicated. The plantings were “something of a fruit salad”, as Fridjhon makes clear but Red Tape rather avoids saying – rather concentrating on the founding myth (a rather ex post facto one, it seems to me) that Tim was fixated on pinot noir and chardonnay for a “Burgundian” project.

The result, anyway, was some apparently decent wines with names that avoided certification pitfalls by avoiding mentioning varieties (clues were given to vintage and style). The Grand Vin Noir 1981 was from pinot, while the Grand Crû Noir 1982 (the excrescent circumflex on Cru according to Platter) was a blend of pinot, shiraz, merlot and pinotage; the Grand Vin Blanc 1982 was from sauvignon and the Blanc de Blanc blended chenin, gewürztraminer, bukettraube, and semillon. So much for Burgundian claims at this stage. (The struggle to get decent, clean pinot and chardonnay material – including through the famous, rather farcical chardonnay-smuggling adventures – is discussed in the book too.) The quota issue became less relevant after 1985 when farmers were allowed to acquire quotas from other farmers in the area, so HRV could acquire one from its other farm. But it was in fact only in the mid 1990s that most of the non-Burgundy grapes were abandoned and HRV started taking on its present guise – though sauvignon blanc lingered for quite a while.

Incidentally, I was obliged to get much of this information from Platter guides of the time, and it’s a pity that there’s very little about the plantings and winemaking (by Peter Finlayson) in Red Tape. Nor is there much in the way of context of others’ wine ambitions in the Cape of the early 1980s – Finlayson was, for example, a founder member of the Cape Independent Winemakers Guild, as it was then called. That kind of lack makes the 17 pages of the chapter entitled “Afrikaner Nationalism, the Broederbond, and Apartheid” seem disproportionately excessive (the book is just 240 pages, including a lot of reproduced documents and correspondence, as well as some good stories about Tim’s antecedents and “the making of a maverick”).

In fact, Afrikaner nationalism, etc are significant in this story, even if not so central as to justify such a lengthy exposition. Broederbonders were inevitably the power in the KWV, which had been progressively granted quasi-statal powers by the government, and the wine industry at its higher levels was essentially Afrikaans as well as fully implicated in apartheid. Tim HR came from a genuinely liberal, politically involved family, and such English-speaking liberals loathed Afrikaner nationalism – not always avoiding contempt and hostility for Afrikaners as such. He seems to have been convinced that the obduracy of the authorities in his struggles to get his own way (which he, of course, regarded as the way of truth and justice and of advance for the wine industry) involved prejudice against him as an “Englishman”.

It probably did – Bridgid HR shows clearly that trangressions of the “Crayfish Agreement” rules against invoking French wine appellations were not only carried to absurdly inappropriate lengths, but that other (Afrikaans) transgressors were not treated as harshly as was Tim. To me too there is no question but that the KWV was devoted to the interests of (largely Afrikaans) grapefarmers rather than to the development of a fine wine industry. I have not a shred of sympathy for that regime, but, frankly, I do feel a touch of sympathy with the various officials and their secretaries being bombarded with argumentative letters from a rich, English-speaking Johannesburger and newcomer to the wine industry, who felt so deeply convinced that the law was wrong and that he was entitled to get his own way because it was so eminently right. Would it be surprising if they dug their heels in when they could?

So the struggles and disputes continued about “the letter of the law”, as one chapter is entitled: over the use of “estate”, over the merest mention of Burgundy as an inspiration even in advertising material. The KWV eventually lost, of course – but this book will serve as a good reminder for those who are not well informed about its fundamentally retardative role in South African wine for much of the 20th century.

The final episode of Tim HR’s battles recounted in this book, does not, in fact, have much to do with red tape as such, or something as narrow as wine industry bureaucracy. The context is the international sanctions against South Africa, which were certainly doing damage to the industry, including HRV. Red Tape discusses labour conditions and the activities of the mildly reformist-liberal Rural Foundation, and is rather too generous, in my opinion, about supposed improvements in the 1980s to the generally appalling standards. The Winelands Commitment appeared in 1989, orchestrated by John Platter (and seemingly directed at international publicity as much as local agitation), calling for improvement in winefarm labour conditions and remuneration, as well as an end to the Group Areas Act and apartheid. There were just four signatories (Platter of Clos du Ciel, Hamilton Russell, Simon Barlow of Rustenberg, and Peter Younghusband of Haute Provence. The local reaction, including from the liberal English-speaking press, was predictably outraged. Tim HR, with all his experience as an advertising man, took the story to the British press, to be further excoriated locally. But I’d guess the publicity did a lot of good to his international wine sales.

- Bridgid Hamilton Russell. Red Tape: The untold story of a visionary South African’s battle against bureaucracy, and the the birth of a world-renowned wine region. Quickfox, Cape Town. R395

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.