Entries for the second annual Old Vine Report are now open – wines must be made from Certified Heritage Vineyards (vines that are 35 years and older vines registered with SAWIS and approved by the Old Vine Project).

Entries for the second annual Old Vine Report are now open – wines must be made from Certified Heritage Vineyards (vines that are 35 years and older vines registered with SAWIS and approved by the Old Vine Project).

The report will be based on the outcome of a blind tasting of wines entered within a specific category and includes key findings, tasting notes for the Top 10 wines, buyer’s guide and scores on the 100-point quality scale for all wines entered.

Wines will be tasted by a three-person panel consisting of Christian Eedes as chairman, James Pietersen, CEO of of Wine Cellar, Cape Town merchants and cellarers of fine wine, and Francois Rautenbach, a hospitality and wine specialist, scoring done according to the 100-point system.

For the rules and entry form, click here.

The emotionally-charged Afrikaans word “nederlaag” keeps returning to my mind. It is a word that resonates with poetic sadness, nostalgia – much more than being a simple translation of “defeat”. I’m thinking, not for the first time in recent months, about Nederburg, feeling sad and nostalgic about the romantic wine highs of a great past.

The ring of the name Nederburg once signaled creativity, class, culture. Now, it seems to me, it suggests “defeat”. Perhaps “demise”.

The other day, low on the supermarket wine shelf was the familiar flourish of the name on a pair of screw-capped bottles. (As has happened so recklessly often in the past couple of years, the marketing people seem to have fiddled with the label design again.) The two seemed so lonely: a white Lyric and a red Duet.

The bottles bear a name that once was essentially a boasting masthead for the great and glorious of Cape Wine. Somewhere, on other shelves: Nederburg Stein, Rosé, Baronne, some ‘Winemasters’ (including the strange Double Barrel Reserve). Apparently Heritage Heroes (ironically named) and some Private Bins are available from the tasting room in Paarl and the Vinoteque. Pretty out of sight, if you ask me.

Since the sell-out of Distell, the name Nederburg is the real heartbreaker. Yes, in Nederburg’s “nederlaag”, defeat is more like a slow demise. Not sure the name will survive, given what certainly seems like a betrayal of its heritage and importance in South African wine history. (The way famous names like Zonnebloem and Fleur du Cap and the brandies have been treated, doesn’t bode well.)

If any wine brand reflected cultural elegance, it was Nederburg.

Nederburg held up its cultural and vinous status in numerous ways. In the arts there were the sought-after grand prizes for opera and ballet. There were Nederburg concerts and art. The wines were associated with creativity and discernment.

The great back story of the founding of the Paarl estate was polished and well presented, making Nederburg wines shine even brighter. With the manor house as setting, it maintained a cheerful golden narrative of that history to visitors. Whatever the actual state of the vineyards around the farm, the name brought prestige to the Paarl appellation when the region wasn’t much the viticultural mode.

There was, of course, the famous and fabulous Nederburg Auctions, first held exactly half a century ago this year. It was a deft move, using the Nederburg name that would prove to be a change of course for fine South African wine and the prices it could achieve in the right circumstances. That Saturday of the first auction on the Nederburg lawn in 1975 was a SA wine milestone.

At the helm of the winery then was the colourful Günter Brözel, a man who embodied the poetical and professionalism in the art of wine. He is the generous ghost who, today, inspires and spirits on the adventurers and avant-garde in Cape cellars. His Private Bin wines and the special releases were the foundation of the auction, but also pointers to fine-tuning and experiments. Some of these wines are benchmarks of local wine history: the noble Edelkeur, of course, but annual standouts of which Nederburg Selected Cabernet 1962 and Nederburg Steen 1974 (yes, chenin blanc!) are but two that linger in memory.

Famous wine personalities came to open, investigate, chit-chat and buy at the auctions. A flourish of creativity swept through the country’s fashion world as top designers brought their garments to the flashy show in Paarl. Awards were given. The name ‘Nederburg’ held it all.

The auction grew to become one of the world’s top social wine events. It did more for promoting local wine to the world than any other project, weaving wine excellence and the image of the historical brand into the fabric of other cultural fields. Nederburg then was highly polished. Until the bean counters pulled the plug.

When contemporary marketing “experts” talk about communicating the ‘stories’ of wine labels, the narrative of Nederburg is one for the books.

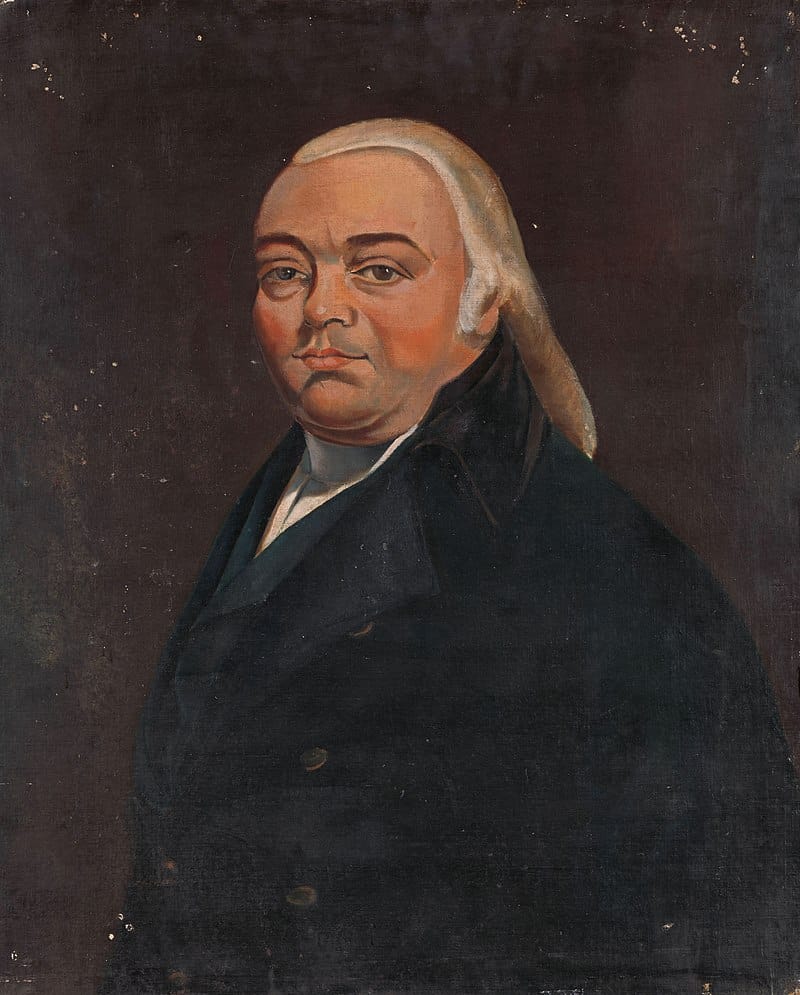

Sebastiaan Cornelis Nederburgh (1762 – 1811).

Carefully curated by the then Stellenbosch Farmers’ Winery (before Distell), it honed the romantic tale of the founding of the Klein Drakenstein farm that Philippus Bernardus Wolvaart received from the Dutch East India Company in 1791. He named his estate after the commissioner-general at the Cape, Cornelis Nederburgh. And so the story unfolded over the decades.

Parallel to punting this exceptional wine history, SFW allowed Brözel and his team(s) to wow the wine world with smart wines. Production grew, but there was never a give-up on smaller, dedicated batches and reserve wines. This is the blueprint that his successors like the brilliant Razvan Macici took to new heights.

Now under the auspices of a beer trader, the glory has faded. The cultural submission of Nederburg is a forfeiture of brand, value and significance. (Being Dutch, the beer people may well understand what a “nederlaag” is.)

On that low shelf at PnP, the bottles the other day suggest that the music of Lyric and Duet is indeed a sad song. A dirge of defeat perhaps. The ‘nederlaag’ of Nederburg.

The controversies and scandals once surrounding the Stellenbosch estate Quoin Rock – before the current regime I hastily add – are fun to recall, but not to be much indulged here. I mentioned some of them (from the SARS-forced sale of the property, hitherto owned by “shameless liar” and tax dodger Dave King, via its auction to Wendy Appelbaum, the sale cancelled because of apparent sharp practice by the auctioneers) when I reported on my 2015 visit to Quoin Rock. That was during the brief tenure of the eminent Chris Keet as cellar master and viticulturist – which soon transformed into his appointment as a consultant (still obtaining).

So, one billionaire pulled back and another one came in. In fact it seemed for an uncertain moment that Quoin Rock had been sold to nightclub king and ex-convict Kenny Kunene and a Ukrainian businessman, Denis Aloshyn, but (fortunately, I feel!) things soon somehow resolved into what we know now: that it was bought by another Ukranian industrialist (and former Deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine), Vitaliy Gaiduk in 2012. Mr Gaiduk is a serious wine lover, who’d been looking around the world for a wine property and was seduced by Stellenbosch during a chance visit. As well he might have been, as anyone who visits these magnificent slopes on the Simonsberg, not to mention the estate’s associated property in Aghulhas (from where Quoin Rock actually got its name), could attest.

Vitaliy’s son Denis became the Quoin Rock CEO. And this has clearly been an excellent thing for reestablishing the brand and building new foundations for it. Work started immediately on doing what was most necessary – fixing infrastructure like dams and restoring or replanting vineyards that had been neglected. Modernising the cellar came next, and some great designing of public spaces by Denis’s architect wife Yuliya Gaiduk (who’s credited as the winery’s Visionary, with a range of image responibilities). The neighbouring farm, Knorhoek, was puchased later and the two properties reintegrated – Quoin Rock had in fact been a subdivison from Knorhoek in 1998.

Having the priorities right was a good sign – as, in fact, was the fact that it seemed to take a good few years to offer a portfolio of wines and to open to the public. It was only in 2018, six years after the purchase, that an article, presumably an advertorial, on wine.co.za appeared entitled A New Era in Winelands Luxury as Quoin Rock Reopens. It quoted Denis Gaiduk’s ambition: “The philosophy of the company is to build one of the best wineries in South Africa…. From the beginning we said that there would be no compromise on quality.” The 2019 Platter’s Guide, after a few years of mere teasers, rated pretty favourably a range of wines – most of whose names, six years later we would actually not recognise, suggesting that it was in fact a rather tentative “reopening”.

Apart from the stated aim of quality, the mention of luxury in that article’s title is significant, however, as it has become clear that this concept (and orientation) is central to the new Quoin Rock. The website makes that clear enough, with overblown language and chic design – and even the winemaker, dragged from his barrels and tanks, wearing a black suit! I confess that in the past few years I have resisted PR/media invitations from the estate because they seemed to indicate (giving a dress code – white and gold was it? – for a launch of their bubbly on a yacht in Table Bay Harbour, I recall) an orientation to bling and ostentation that didn’t seem to me to promise particularly well for the wines, or the conversation for that matter.

I was pleased, though, to get an invitation from Marketing Manager Kris Snyman to make a proper visit, and spent a morning with him, Denis Gaiduk and winemaker Schalk Opperman – whom I’d last met when he was doing good work at a rather different setup, Lammershoek in the Swartland; he arrived here in 2020. Viticulturist Nico Walters was unfortunately ill, but the rest of the team was able to tell me useful stuff as we drove around the extensive property. It really is an extraordinarily beautiful place, much of it left wild (there is some clearance of alien vegetation); I saw a herd of wagyu cattle on a hillside, and some large orchards of espaliered almond trees in full, fragrant blossom – Denis spoke of the need to diversify income streams.

We made for the Knorhoek homestead and there, on a stoep in idyllic surroundings (not a touch of bling!), tasted a good selection of the range. No bling in the wines either; they struck me as very good, mostly restrained, and responsive to the terroirs they come from – including, of course, Agulhas for some of the whites. Bubbles to start: the pinot-based Festive Series Cap Classique, succulently delicious and fresh and dry enough; and the Black Series 2018, a more equal blend of pinot and chardonnay, five years on lees adding to the rich but lively and complex dryness – an impressve wine.

There are two wines from the Knorhoek vineyards, labelled as such, and designed to express “heritage and tradition”. They are less expensive than the Quoin Rock ranges (“international fine wine”, by contrast), and in fact count as pretty good value. The Chenin Blanc 2023, from a 1980-planted vineyard, pleasingly combines stoniness with peachy fruit – and rather unnecessary oak notes; very tasty and with some depth (R245). The Knorhoek Cabernet Sauvignon 2021 (R325, but I believe it’s due for a price rise) has pure and full fruit with well integrated oak, and is decently structured and properly dry.

The Quoin Rock Black Series are generally pricier. The Chardonnay 2021, at R495, is not over-ambitiously so for the quality. Like the Knorhoek Chenin, there’s a third new oak but better integrated (a few years helps, of course). It’s lively and fresh at 12.5% alcohol, yet not without a touch of winning richness in its subtle unshowiness. We didn’t taste the Nicobar sauvignon from Agulhas, but I was pleased to hear that this once rather famous label is being revived.

As to the reds, the Shiraz 2019 seemed to me standard older-style-Stellenbosch – ripe and rich and dark-fruited, with a touch of sweetness to the finish. (I wonder if Schalk’s Swartland experience with this variety is going to push future vintages in a lighter, fresher direction.) But undeniably attractive and approachable. I more admired and enjoyed the cab-driven Red Blend 2019, with its subtle, fresh aromas – a dry-leafy fragrance hinting at the cab franc component. The tannins nicely in place, but already very approachable, the whole rather elegant, with a sufficiently dry finish. (Schalk later gave me a bottle of the 2021 to take home, when I said that I tended to prefer a little more tannic-grunt, and that younger wine did indeed have it; it was lovely to drink, especially on the second night.) These reds are R750.

A final pleasure was the Vine-Dried Sauvignon Blanc 2024 (R1100 per half bottle), one of the loveliest straw wines I’ve had – fresh and poised in its unchallenging sweetness, charming and precise.

I suspect that the coming years will see the prices of the wines rising, to fit in better with the establishing Quoin Rock image. Rich people expect, and want, to pay more for their wines. The whole package – tasting venues with careful experiences for visitors, fine food and grand accommodation and function facilities, all set among the vast beauty of the environment – is implacably luxurious in its excellence, and breathes expensiveness, intended only for the rich and demanding. This is still a comparatively rare Napa-type situation in South Africa, with Leeu Estate and Leeu Passant wines in Franschhoek already there, for example. There’s no reason why the Quoin Rock wines, not totally ready yet, should not come to that party.

I love reading about viticulture back in the day. I’m talking here about the time before the mid-19th century. I remember reading one account of how vineyards were planted in Burgundy (or Bourgogne as we are now supposed to call it) in the past. The winegrower would plant cuttings in the ground in rows around a metre apart. The vines would grow up, and attached to stakes, would begin yielding grapes. It would be pruned back to three buds each year. Then every decade or so, a trench would be dug, some manure added, and the trunk laid down with just a few nodes above ground (three buds), attached to a stake. Then a new trunk would grow up, and this process would be repeated each decade.

After a while, the orderly rows would be lost and the vineyard would effectively be en foule (in a crowd). Any weeding was done by hand, so this didn’t matter. There wouldn’t be trunk disease, because the trunks got no older than 11. Planting could be done by the grower: you just plant cuttings, so no need for nurseries. And genetic diversity would be maintained by massal selection. This was before phylloxera, so no need for rootstocks. And it was before downy and powdery mildew arrived from the USA, so no need for spraying. The manuring when the trunk was laid in the ground would help maintain fertility, as would the lack of deep ploughing, so soil microbial communities would be doing a lot of the work in keeping the vines nutritionally happy.

It was into this relative Eden than the American scourges of phylloxera and the two mildews arrived in the mid-to-late 19th century that has given viticulture a bit of a sustainability problem.

Now, vineyards are among the most heavily sprayed crops, and it’s no longer possible in most regions of the world to plant from cuttings or do layering (marcottage) or trunk burial. The biggest sustainability issue is from the two mildews, which mean that if you want a crop in most regions worldwide you will have to spray things onto your vines that you’d rather not have to spray.

Spraying vines is expensive. It introduces chemicals into the vineyard that can create problems. And it also causes compaction of soils. Those lucky regions that don’t have growing season rainfall – and we are talking here of Mediterranean-like climates such as vineyards around the Mediterranean, in the Western Cape, and in California – don’t have much of a problem with downy mildew. But powdery mildew is a problem everywhere. While at the beginning stages of the season a bit of dampness does encourage powdery, once it’s there it needs no moisture and likes warm temperatures, making it highly problematic. In New Zealand, for example, growers must spray every week at the peak of the growing season. It’s a major issue there. In a typical season in areas where both downy and powdery are problematic, growers might do 14 spray passes. That’s a lot.

The remedies for powdery and downy were initially discovered quite soon after they arrived in Europe. Powdery came to Europe via the hot house of an English gardener. Edward Tucker, in Margate. In 1845 he noticed it on one of his vines. Tucker looked at it under a microscope, and decided that this disease was very similar to peach mildew. And back in 1821 an Irish gardener called John Robertson had successfully used sulfur to control peach mildew, so Tucker tried it too, and it worked. Robertson had mixed sulfur with soap, whereas Tucker mixed it with lime. Despite this successful treatment, powdery mildew spread, across the UK and to France. Before long, it was a major problem across the vineyards of Europe. It was first spotted in French vineyards in 1847, and then in Italy in 1849. In the early 1850s it caused massive problems economically, as winegrowers learned to get to grips with the best ways of applying sulfur as a remedy. Since then, it has been an ever present in the vineyards of the world.

Downy mildew arrived in France in 1878, most likely via the American vines imported after phylloxera broke out. The chemical fix, still used today, was discovered by Pierre-Marie-Alexis Millardet who made this observation fortuitously. In October 1882, Millardet was in the vineyard of Château Beaucaillou in the St Julien region of Bordeaux, and noticed something strange. Rather than leaves ravaged by downy mildew, he saw vines with a healthy canopy. The leaves had been covered with Verdigris – copper sulfate mixed with lime – to deter thieves. It gave them a bluish green colour, but it also stopped the mildew in its tracks. Over the next two years, Millardet revised this treatment, which became known as Bordeaux mixture. The recipe is simple. Take 100 litres of water and 8 kg of copper sulfate, and mix them. Then make a milk of lime, by dissolving 15 kg of rock lime with 30 litres of water. Just before spraying, combine the two, and use it all up within a day or two. 50 litres of this concoction treated 1,000 plants. So, to treat one hectare would take around 500 litres. This solution was effective, and variations on the theme of this Bordeaux mixture are still in use today.

If you farm organically, these chemical remedies are permitted. If you aren’t organic, you can use potassium phosphonate alongside copper for downy mildew and this is very effective, reducing the amount of copper needed. Or you can use what are known as systemic fungicides, which work from the inside of the vine and specifically target certain mechanisms of action of the disease-causing organisms. These are generally more effective that copper and sulphur, although conventional growers may well use a mix of the older remedies and the newer to stop resistance occurring to the systemics. Copper and sulphur are what’s known as contact fungicides, and they work only if they are covering the vine’s surface. If it rains, they get washed off.

Neither approach is all that sustainable. The systemics may affect the fungal populations in the soil, but this hasn’t been well studied. Sulphur isn’t too bad, but residues often remain on the grapes that can then cause fermentation issues, and it needs applying frequently, leading to soil compaction and increased carbon footprint. Copper is the real baddie, because it ends up in the soil and is toxic to soil life. But if you are organic, there are no real alternatives. Various teas and preparations can give a little protection, but alone can’t give the protection that copper can.

The truly sustainable solutions? Grow vinifera only where disease pressure is low. Elsewhere, we really need new vine material if we want to farm sustainably. A lot of breeding work has been taking place to produce hybrids that have the true resistance genes against powdery and downy, and more than one copy of each to stop the disease becoming resistant to them in turn. And these are backcrossed with vinifera varieties to produce a resistant vine that’s mostly vinifera and has good wine quality. These are catching on in Europe, and they have just started being imported to Australia and New Zealand. Australia also has its own disease-resistant vine breeding program.

There’s also interest in taking well known vinifera varieties and fiddling with their genetics to make them resistant. Genetic modification, introducing the resistance genes from American and Chinese varieties, is possible and has been done, but people aren’t ready to accept genetically modified vines right now. An alternative approach is gene editing, introducing nothing but using special genetic scissors to take out susceptibility genes, and thus making vinifera more-or-less resistant. Trials have gone as far as experimental plantings of edited Chardonnay in Italy, but protestors sabotaged them. These aren’t considered genetically modified in many countries, but Europe is sitting on the fence a bit.

True sustainability is something we should be aiming for. In many climates, while I love organics, it’s really not all that sustainable because of all the spraying.

Franschhoek property Boschendal will soon unveil Arum, a restaurant from the acclaimed FYN Group. Led by chef-founder Peter Tempelhoff, culinary director Ashley Moss, and sommelier Jennifer Hugé, Arum – named for the lily – celebrates the land through fire, cooking incorporating smoke, char, and light grilling. Housed in the historic Werf building, the menu will feature over 40 farm-grown ingredients, while the new bar offers inventive cocktails. Opening preparations are underway, with all positions currently open – resumes to work@arum.co.za