SA wine history: On the Cape’s first highly acclaimed winemaker

By Joanne Gibson, 28 August 2018

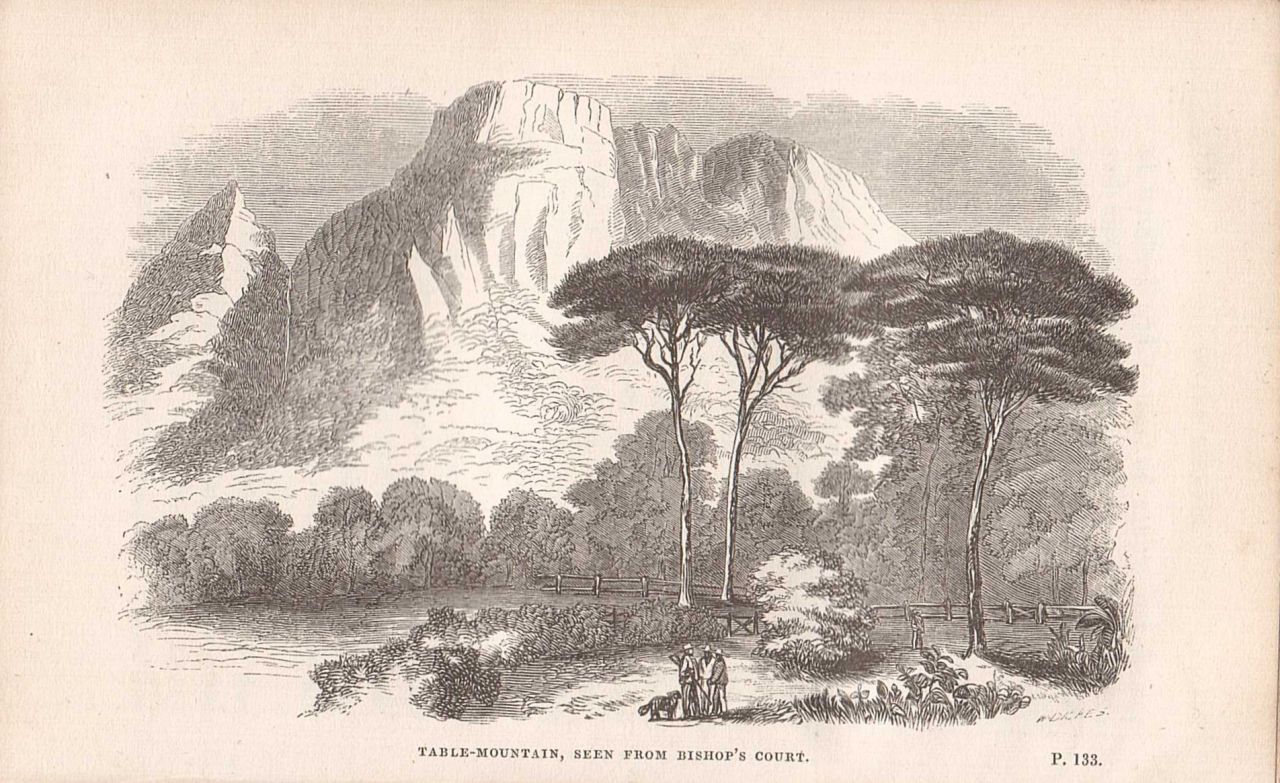

It was exactly 360 years ago this week, ‘during the waning moon’, that Jan van Riebeeck planted 1,200 vine cuttings on the land he’d been given permission to cultivate at the Bosheuvel, today Bishopscourt, with the help of a few slaves and vrijburghers (‘free men’ who’d been released from their Dutch East India Company contracts to farm along the Liesbeeck River, from present-day Mowbray to Bishopscourt).

The previous week, on 21 August 1658, he had visited these vrijburghers to offer them as many vines as they wanted to plant: ‘Some excused themselves for their ignorance … and others took one or two only to plant against their houses, none being inclined to give up land for them,’ he recorded.

He repeated the exercise a year later, noting that a few cuttings were ‘almost forced upon’ the vrijburghers.

Only in September 1660 could he finally report that a few men had seen his Bosheuvel vines growing ‘most excellently’ and were ‘nicely following suit’ and planting ‘hundreds of stocks’. These were no doubt the farmers that his replacement as commander, Zacharias Wagenaar, found to be ‘very good, industrious, hard-working men, who take very good care of their families, and have hitherto delivered the greater part of their crops to the Company as they are contractually bound to do’. (As opposed to the ‘many lazy useless men, and many more vagabonds, or abandoned shameful drunkards … who proceed in their irregular and reprobate mode of life…’)

The question is whether any noteworthy winegrowers can be identified from those first decades of European settlement at the Cape, and the answer – remarkably – is yes.

One of them was Jan Pietersz Louw whose Rondebosch/Newlands farm Louwvliet (on land now incorporating the Newlands Rugby Stadium) had 20,000 vines growing by 1691, not to mention a ‘pershuijs’ with a wine press as well as over 30 barrels in various sizes.

Slightly to the north, Albert Gildenhausen also had 20,000 vines according to the December 1692 Opgaafrol or tax census, and in 1712 his farm, Roodenburg, and its buildings were valued at 16,000 guilders (6,000 more than the main portion of Vergelegen, with its magnificent homestead, sold for that same year).

And not only did Jan Dirksz de Beer of Ekelenburg and Veldhuijsen (south of Louwvliet) have 25,000 vines planted by 1692, but by 1698 he also owned 25 slaves – a high number for a vrijburgher in those days.

Best known for his wine in the 1660s and 1670s, however, was Jacob Cornelisz van Rosendael, who had been one of the first men to receive his Letter of Freedom on 14 April 1657, when he was enumerated as a soldier. The very first land grants were communal, so he initially farmed alongside Steven Jansz (later known as Botma), Hendrick Elbertsz and Otto Jansz on the east side of the Liesbeeck in today’s Rosebank and Rondebosch, then referred to as Steven’s Colony or Hollandsche Tuin (Dutch Garden).

He and Jansz farmed as partners to the north of Botma and Elbertsz until Jansz was appointed as supervisor of Robben Island, whereafter Rosendael seems to have single-handedly applied himself quite well to his agricultural responsibilities (apart from one recorded incident of illegal sheep bartering to which he confessed on 16 February 1664).

On 9 November 1664 he married Catharina Jansz van den Bergh, recently arrived from Amsterdam (where she was rumoured to have worked as a prostitute named Grietjie). Whatever her background, Rosendael was now more ‘permanently settled’ (just as Van Riebeeck had hoped in his repeated requests for ‘lusty maidens’ to be sent to the Cape) and on 28 November 1665 he made a very significant purchase on public auction: he acquired Van Riebeeck’s Bosheuvel property, complete with ‘some thousands of vines’, for 1,600 guilders.

Rosendael could probably afford Bosheuvel (albeit in three instalments) because he had been awarded a pacht or lease to sell alcohol earlier that year, a year in which it was officially noted that ‘among all the free inhabitants here, nobody is able to achieve more comfort, better prosperity, and greater advantage than those who have long been allowed to tap strong alcohol’ (in return for which the pachters – there were four – now had to pay a ‘mild excise’).

The terms of the Bosheuvel sale were that the Cape authorities retained the right to press the entire 1666 harvest and also to take 6,000 cuttings to plant at the Company’s Orchard at Rondebosje. In February 1666, 1½ leaguers of ‘aengename, lieffelyke’ (pleasant, lovely) wine were duly pressed.

As the years went by, Rosendael provided vine cuttings to other vrijburghers as well as to the Company. In 1670 he was also granted the unprecedented privilege of selling wine of his own making, in large as well as small quantities, to vrijburghers and ‘people of the ships’ alike. The Council of Policy praised him for ‘showing great diligence in extending his vineyard’ and also exempted him from the excise duty that would be imposed on other farmers wishing to send their surplus wine to Batavia.

In fact, he must have been very highly regarded, given that his pacht wasn’t taken away even after he was caught smuggling large amounts of alcohol from ships in Table Bay in 1673 (whereas his accomplice, the Company dispensier Willem van Dieden, lost his job).

Unfortunately, Rosendael died sometime before 19 July 1676, which is when his widow married Tobias Marquard (the first to register the title of Bosheuvel officially). To date I have been unable to find out what happened to Rosendael’s children – that is, apart from his first daughter, Jannitjie, whose death in a wagon accident in February 1667 was recorded thus: ‘The fiscal and surgeon were sent out to investigate and reported that the wheels of the wagon had gone over the head of the child, and thus crushed its brains.’

Perhaps Johanna, Cornelia and Cornelis Rosendael left the Cape with their mother and stepfather in 1686 after he was reported to the authorities for beating a slave to death. But that’s a story for another day…

BIBLIOGRAPHY/RECOMMENDED READING

Leibbrandt, HCV: Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope (Journal, 1662-1670; Journal, 1671-1674 & 1676; Letters despatched from the Cape, 1652-1662, parts 2-3), originally published by W.A. Richards & Sons, 1896-1905, digitised by University of California Libraries (https://archive.org)

Schoeman, Karel: Early Slavery at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1717, Protea Book House, 2007

Van Rensburg, J.I: Die Geskiedenis van die Wingerdkultuur in Suid-Afrika tuidens die Eerste Eeu, 1652-1752. MA Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, 1930

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.