SA wine history: The TWO celebrated producers of legendary Constantia wine

By Joanne Gibson, 15 January 2019

2

In my last column, I introduced the Colijns of Constantia who were all but written out of history during the Apartheid years because of their black/slave roots. I finished off by claiming that they made the world-famous sweet Constantia wine right through the glory years – alongside the more celebrated Cloetes of Groot Constantia – a claim which probably requires some substantiation.

As mentioned previously, one of the first to visit both Groot and Klein/Hoop op Constantia in 1741 was Dutch East India Company (VOC) official Otto Mentzel (later chief of police at Frankfurt am Main in his native Germany) who recorded: ‘Both produce similar red and white wine; only connoisseurs can distinguish some difference in flavour.’

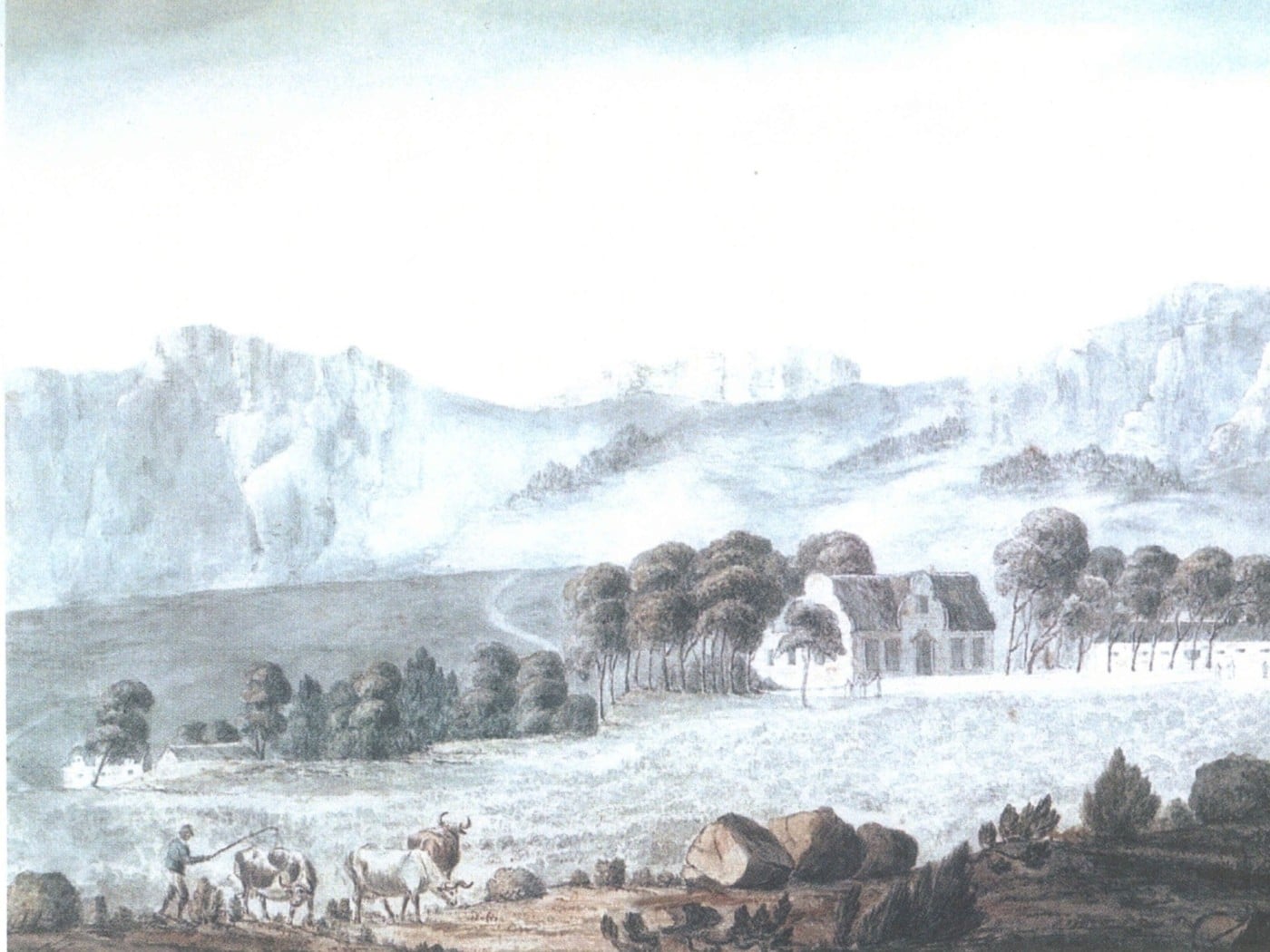

Lady Sophia Hamilton’s 1799 watercolour painting of Constantia shows Klein/Hoop op Constantia tucked in a hollow below Groot Constantia (which in fact absorbed its small but historically illustrious neighbour in the mid-1970s). Now national monuments, the old Colijn buildings are still there, although the homestead no longer has the three front gables it boasted in its heyday. (Source: Schutte, 2003)

In 1769, when French seafarer Viscount Louis de Bougainville visited Constantia, Klein/Hoop was in the hands of Johannes Colijn’s widow, Johanna Appel, and her second husband, Lambertus Myburgh (from whom Johannes Nicolaas Colijn would take over in 1776), while Groot was owned by Jacobus van der Spuy (the step-son of Johannes Colijn’s brother-in-law, Carl Georg Wieser). De Bougainville wrote that Constantia was ‘distinguished into High and Little Constantia, separated by a hedge, and belonging to two different proprietors. The wine which is made there is nearly alike in quality, though each of the two Constantias has its partisans’.

In late 1778, the wealthy and influential Stellenbosch landowner Hendrik Cloete acquired Groot Constantia for 60,000 guilders, slightly less than Johannes Nicolaas Colijn had paid his own mother for the much smaller Klein/Hoop op Constantia two years previously (61,680 guilders).

Cloete and Colijn were first cousins once removed and it seems they had a good relationship. ‘The big oak forest between Colijn and me has been uprooted to make place for more vineyards,’ wrote Cloete in a letter to his Utrecht-based friend Hendrik Swellengrebel on 30 March 1780. In a letter dated 1 March 1788, Cloete’s wife added a postscript thanking Swellengrebel for some biscuits that she and Mrs Colijn, ‘the lady of Little Constantia’, had eaten together with much pleasure.

While Colijn reportedly led ‘a very simple burgher life’, Cloete was famously flamboyant. In 1783, for example, the French ornithologist Francois le Vaillant was taken aback by ‘the haughtiness of this lordly vine-dresser’ as well as ‘the parade of ostentatious grandeur, and the air of stately superiority’ at Groot Constantia. He was at pains to point out that ‘Lesser Constantia’ was held in the same esteem: ‘It has even sometimes happened that the produce of it has been sold for a larger sum.’

What Colijn and Cloete shared was outrage that the VOC was still paying them the fixed amount negotiated with Johannes Colijn in 1736 – 100 Rixdollars per leaguer of red wine and 50 Rixdollars per leaguer of white – now ‘sufficient to utterly impoverish [them] and help [them] to beggary’ – at a time when visitors were prepared to pay up to 640 Rixdollars per leaguer, knowing how sought after the wines were in Europe (it’s a fact that Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had more Vin du cap de Constance in their cellar at Versailles than Burgundy, the traditional wine of French kings).

In 1788, when the VOC offered to pay them 25% of future profits, Colijn broke down his costs (right down to the food and clothing required by his 52 slaves) to prove that this ‘douceur’ still wouldn’t allow him to balance loss and profit – and he warned that if he was forced to ‘desist from continuing the business […] all future profits would cease, which the Company has hitherto enjoyed’.

Cloete, meanwhile, argued that the transfer deeds for his farm had made no mention of any historic obligation to supply the VOC (‘or I would have carefully bewared of buying such a place’) – and in 1793, he eventually persuaded visiting VOC commissioners-general Nederburgh and Frykenius that the binding agreement of 1736 only applied to the Colijns of Klein/Hoop op Constantia. The result was a new agreement that Groot Constantia should supply the VOC annually with only 15 aums each of red and white wine (‘the best and highest flavoured’) for double the old price.

Colijn immediately demanded equal terms, claiming that his wines were often preferred by ‘knowledgeable foreigners’ and had recently achieved higher prices on auction in the Netherlands. He argued that a ‘prejudicial distinction’ in the price paid by the VOC would naturally discredit his wines and lead to his family’s demise. He therefore ‘humbly’ requested that a contract similar to Cloete’s be drawn up – and the same ‘rights and privileges’ were duly granted to him on 27 September 1793.

Needless to say, these new contracts again took no consideration of rising costs and inflation, and would be a source of rising resentment for the next generation of Constantia proprietors, Hendrik Cloete Junior and Lambertus Johannes Colijn, especially after the British took occupation of the Cape in 1795. In 1797 ‘the farms and vineyards of great & little Constantia’ were officially ordered to continue supplying their new government on the same terms agreed with the VOC four years previously. ‘I cannot discover the smallest ground which could justify one in waiving a right now possessed by His Majesty,’ proclaimed Cape Governor George Macartney,

British ‘rights’ notwithstanding, Constantia business boomed. In 1805, Lambertus Colyn (as the surname was now more commonly spelled) expanded Klein/Hoop by incorporating the neighbouring farm Nova Constantia (originally part of Bergvliet) – and it is Colyn we have to thank for a detailed description of how the famous wine was made, covering everything from soil preparation (‘one basket of manure is used for four vines’) and pest control (‘placing rolled-up vine leaves in the vines to catch weevils’) to barrel treatment (‘those with a musty smell must be kept full of clean water for eight days’) and fining (‘each cask with a basin of sheep- or goat’s blood’).

As far as visitor accounts go, when Russian vice-admiral VM Golovnin called at the Cape in 1808, he wrote: ‘The Constantia wine is made from grapes at only two places, the one next to the other… Some people say that in one of the Constantia brands, the white is superior and in the other the red, but the owners themselves deny this.’

In 1811, English explorer, naturalist, artist and author William Burchell visited Groot Constantia and noted that the proprietor’s affluence derived from wines which ‘[could] not be made on any other spot in the colony’. He hastened to add, however that this was ‘not literally a monopoly; for the adjoining vineyard, called Little Constantia, produces a wine scarcely inferior’.

In 1818, the French surgeon Joseph Paul Gaimard and two companions visited Constantia to see for themselves the place ‘so justly celebrated for the excellence of the wine it produced’. They stopped ‘briefly’ at Groot Constantia (‘the high trees that surround it give it a certain air of grandeur’) but spent several hours at ‘the farm of M. Colyn, known as Little Constantia or The Hope of Constantia’.

In his journal, Gaimard listed the wines produced by Colyn, namely Constantia (white and red), Pontac, Pierre (reportedly made from Ugni Blanc) and Frontignac, and noted that they all cost 250 Rixfollars per half-aum (equating to a staggering 2,000 Rixdollars per leaguer), except for the Frontignac, which cost 300 Rixdollars per half-aum. ‘For my part, of all the wines I like the Constantia best, and white or red equally,’ wrote Gaimard, who particularly enjoyed ‘an excellent pudding of strawberries in Constantia wine with biscuits’.

When the merchant and philanthropist William Wilberforce Bird visited both Constantia farms in 1822 to taste the wines ‘sent to England as presents to soften the temper of ministers, and to sweeten the lips of royalty itself’, he noted that ‘the Little Constantia, as it is termed, produces more wine than the Great Constantia’.

In 1829, British naval officer James Holman visited both ‘Great’ and ‘Little’ Constantia, concluding: ‘There is so little difference in the quality of the wines produced on the two estates that a person must be a very extraordinary judge who could discriminate the precise difference between them.’

In 1830, the American naval chaplain CS Stewart was received with ‘much politeness’ and served ‘an elegant collation’ by Jacob Cloete, after which he visited ‘Lower Constantia, the possession of a Mr Colyn’ where he was ‘received in the same hospitable and kind manner by this gentleman, and conducted over an establishment equally rich and beautiful’.

That same year, British major-general Godfrey Charles Mundy ‘passed the gate of Groot Constantia, the property of Mynheer Clooty’ and – after ‘descending a rustic lane, like those of Surrey, and diving under a dark and beautiful arcade of oaks’ – arrived at the ‘goodly mansion’ of Little Constantia, of which he wrote: ‘The fame of its wines and its vines, and the civility of its master, are sufficient inducements to visitors.’

Visitors may no longer be welcome at this ‘goodly mansion’, which is now a national monument used as a private residence on Groot Constantia (which absorbed Hoop op Constantia in the mid-1970s), but for the Colyns to continue being denied their rightful place in the history books, at least, seems unforgiveable to me.

Bibliography

Burman, Jose, Wine of Constantia (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1979)

Leibrandt, HCV: Précis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Vol 16: Requesten (Memorials) 1715-1806

Schutte, GJ (ed): Briefwisseling oor Kaapse Sake 1778-1792 (Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 1982)

Schutte, GJ (ed): Hendrik Cloete, Groot Constantia and the VOC, 1778-1799 (Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 2003)

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Wiktor | 28 January 2021

Joanne Gibson ,

I was contacted by Cathy Marston through Susan McNaughton for your articles. I am writing a book on South African winemaking and vineyards. However, I still don’t understand the story of Constantia, or actually only Groot and Klein Constantia. Is the present one only related to the one separated by the Cloete family from Groot Constantia in 1823, or to the original Klein Constantia formed after the death of van der Stel, together with Bergvliet and Klein Constantia, later called Hoop op Constantia? I think it concerns the spun off from Groot Constantia. On the internet and beyond, everyone skips things if they’re unfamiliar with them. Then there are gaps in history.

I think that for the readers from Cape it is all clear, but for the reader from Poland who knows little about South African winemaking, it may not be understandable. Of course, I could shorten the history of these vineyards to a few sentences, but they are historical vineyards that, although briefly, I would like to describe a bit more. The book will be a handbook. Would you be willing to give me this little information about Constantia? The ladies mentioned above write to me that you are a specialist in history, especially in Constantia vineyards. I will be sincerely grateful for the information.

Best wishes

Wiktor Zastrozny

wiktor@festus.pl

http://www.festus.pl

Joanne Gibson | 28 January 2021

Hi Wiktor,

The short answer is that the Klein Constantia we know today was part of Groot Constantia until 1823. The original Klein Constantia (later renamed Hoop op Constantia) was formed in 1716, following Simon van der Stel’s death in 1712.

What my reasearch has shown is that Klein/Hoop op Constantia was the more important producer during the first half of the 1700s, thanks to its proprietor Johannes Colijn resuming winegrowing and negotiating annual VOC shipments in the 1720s. Without Colijn there would have been no legendary Constantia! My theory is that he was completely written out of history during the Apartheid years because he was the son of a black woman… It really annoys me that only the Cloetes are ‘famous’ today, when the truth is that they only arrived in Constantia 60 years after the Colijns! And BOTH families made Constantia wine until the mid-1800s.

As you say, there are gaps in the history, and I am doing my best to fill them. Have a look at the history on the Klein Constantia website: https://www.kleinconstantia.com/about/our-history/

Best wishes,

Joanne (joanne@winewriter.co.za)

PS. Hoop was/is right next door to Groot Constantia (slightly down the hill). In the 1970s the property was acquired by Groot Constantia, and in fact the CEO of Groot Constantia now lives in the Hoop manor house. I wish Groot would start embracing the Colijn history, which I feel is so important post-Apartheid. It no longer needs to be hidden that the southern hemisphere’s most famous wine in history was put on the international map by the son of a black woman, born into slavery!