The eighth annual Cabernet Sauvignon Report sponsored by multinational financial services company Prescient is now out.

The eighth annual Cabernet Sauvignon Report sponsored by multinational financial services company Prescient is now out.

94 entries were received from 76 producers and these were tasted blind (labels out of sight) by the three-person panel, scoring done according to the 100-point quality scale.

The top 10 wines (with rating alongside) are as follows:

Blaauwklippen 2017 – 93

Croydon Vineyards Covenant 2017 – 95

Delaire Graff Reserve 2017 – 93

Fleur Du Cap Series Privée 2016 – 92

Kleine Zalze Vineyard Selection 2017 – 93

Le Riche 2016 – 93

Neil Ellis Stellenbosch 2017 – 92

Plaisir de Merle 2015 – 93

Rust en Vrede Estate Vineyards 2017 – 94

Strydom Rex 2016 – 93

To read the report in full, including key findings, tasting notes for the top 10 and scores on the 100-point quality scale for all wines entered, download the following: Prescient Cabernet Sauvignon Report 2019

To view a photo album from yesterday’s announcement function, CLICK HERE.

To find out more about Prescient, CLICK HERE.

Given that the Sauvignon Blanc-Semillon blend that is GVB White from Vergelegen in Somerset West is rightfully much celebrated, I was intrigued to revisit the two component parts as single-variety wines. Tasting notes and ratings for the current-release 2017s as follows:

Vergelegen Reserve Sauvignon Blanc 2017

Price: R260

Grapes from the famous Schaapenberg vineyard, 2.5ha in size and planted in 1988 – 60 rows of grapes destroyed by fire just before harvest but still considered one of the best vintages ever by winemaker André van Rensburg. Fermented and matured for eight months in a combination of 2 500-litre foudre and 363-litre stainless steel drums.

An exotic nose of lime, grapefruit, granadilla and blackcurrant with some fresh herbs in the background – recalls New Zealand more than the Loire. The palate is rich and full with coated acidity and a gently savoury finish. Seamlessly assembled, this makes for a wonderfully multi-dimensional drinking experience. Alcohol: 14.41%.

Editor’s rating: 92/100.

Vergelegen Reserve Semillon 2017

Price: R315

Fermented and matured in 224-litre French oak barrels, 25% new. A rather shy nose with subtle notes of hay, white peach, oak spice and white pepper. The palate is rich and broad with nicely integrated acidity and a savoury finish. Not quite as striking as the Sauvignon Blanc but quite clear to see why the two varieties as grown on this property marry so well.

Editor’s rating: 91/100.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

The wine trade is such an intricate, nuanced business that is so multifaceted and fractured with so many products created to appeal to one market segment or another. But segment the market you must, for without this approach, very little can be achieved in reality. With so many different grape varieties, a multitude of wine styles, from a plethora of wine producing nations, it can, even for professionals, just seem a little bit overwhelming sometimes. In short, we never stop learning. It was one such eye-opening moment of learning in 2001 that brings back interesting memories. Whilst visiting Helmut Donnhoff in Oberhauser in the Nahe, Germany, I will never forget how, one by one, he brought out wine after wine after wine… starting with basic Kabinett Rieslings, then moving on to Spatlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese and then Trockenbeerenauslese. But of course, it did not stop there. There were still the recently 100-point Parker rated Eisweins to taste! After all this bravado and excitement, tasting some of the most momentous, crystalline Rieslings in the world, I was needless to say, in a very happy place.

However, what caught my eye as we were about to leave the winery tasting room was not more stupendous sweet liquid gold Riesling, but in fact a few modest bottles of dry or trocken Riesling. I immediately enquired to Helmut if we could taste these wines. He look puzzled and replied… “Well, of course. But the English market only buys fruity style Riesling. These dry styles only sell in the local German market.” The rest, as they say, is history. My next shipment from the Nahe included 20 to 30 cases of very affordable trocken Riesling that became the first shipment of its kind from Donnhoff to hit the UK market. Almost 20 years later, the dry styles of Riesling from Germany are apparently outselling the sweeter styles across the broader UK market. What of course this product had working in its favour was the ability of producers to write the grape name boldly across the front label. In reality, the dry styles of Riesling were merely meeting a newly created demand that the Australian Clare Valley and Adelaide Hills dry Riesling producers had created in the UK in preceding years with their varietal labelled wines.

In many ways, South African Chenin Blanc was a little bit like Riesling – famous but never a popular or lauded grape in the European markets despite KWV Chenin Blanc being almost as popular and well received as the KWV Roodeberg red blends of the early 1980s and 90s. What South African Chenin Blancs could do, however, was boldly display their varietal name on the front label and register a certain amount of recognition, however benign, with the consumer. This simple and almost trivial factor has in many ways allowed the new generation of high quality South African Chenin Blancs to move past the point of being a regional oddity or enjoyable peculiarity to becoming one of the most desirable and championed white varieties produced from any New World grape growing nation. Of course the noise of this hype and excitement can almost simultaneously be matched by the tears and frustration of the great French Loire producers who have been producing iconic benchmark Chenin Blanc for centuries but without the ability to put the Chenin Blanc variety on the label of their Vouvrays, Saumurs and Savennieres.

The power of the varietal brand and more latterly, the power of the producer brand from the likes of Chris Alheit, Ken Forrester, Eben Sadie and Ian Naude has elevated Chenin Blanc from South Africa to a new level of adoration. For many consumers, it is South Africa who has claimed this variety as their own, as if the glory was somehow stolen from underneath the noses of the once great French estates of the Loire. The varietal brand ownership has been firmly claimed by South African producers and there seems little chance of France grappling this mantle back. As if having some of the greatest Chenin Blanc in the world was not enough, South Africa now has a nuanced offering of not only old vine Chenin Blanc from rock star producers, but it has the unique selling proposition of incredible Chenin Blanc based white blends that have moved the market in a way that no other wine producing nation globally can compete with. Unlike the quirkiness of Austria’s Gruner Veltliner and the spicy unloved loneliness of Australian Semillon, Chenin Blanc is becoming the new Chardonnay, the Chameleon grape that marries itself to unoaked and oaked styles as readily as it does to dry or sweet dessert styles.

This stylistic flexibility has now elevated Chenin Blanc at the premium level, to the status of the only grape variety on the market that has a realistic chance of rivalling the greatest white Burgundy Chardonnays produced. The consumer love affair now has the spice, energy and excitement of a 16 year old on his first date with his girlfriend. More importantly, the demand for South Africa’s best Chenin Blancs is now being driven primarily by on-premise restaurant buyers as well as off-trade connoisseurs and collectors, not by transient fair weather high street consumers. The demand is real, tangible and primed to be long lasting. With South African Chenin Blanc having already confirmed its age-ability credentials, the demand from fine wine merchants looks set to continue growing exponentially creating exciting opportunities for a new generation of young producers like Sakkie Mouton and his incredible maiden sell out 2018 Revenge of the Crayfish Chenin Blanc. So my advice is to buy now before the good stuff is all exported. The demand from fine wine lovers in the UK and beyond has only just begun.

Here are our five most highly rated current-release wines of last month:

Sons of Sugarland Syrah 2018 – 97/100 (read original review here)

Patatsfontein Chenin Blanc 2018 – 96/100 (read original review here)

Babylonstoren Wine Club Semillon 2017- 95/100 (read original review here)

Pieter Ferreira Extra Brut Blanc de Blancs Méthode Cap Classique 2012 – 94/100 (read original review here)

Raats Family Cabernet Franc 2016 – 94/100 (read original review here)

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

Does our new programme of Best Value Tastings (see here) aimed at identifying the best wines selling for between R60 and R100 a bottle reinforce expectations that South Africa is predominantly a source of cheap ‘n cheerful wine (or, even worse, cheap ‘n nasty wine)?

The industry has some major problems, most of which stem from history and official interference rather than terroir or fundamental growing conditions – the KWV for a long time didn’t exactly facilitate the most business-like mindset among growers and then the institutional vacuum brought about by its repurposing has created massive structural instability. As a result, far too much of production is focused on bulk.

Moreover, leaf-roll virus remains endemic and a major constraint on quality while producers are inclined to factor a weak rand into their pricing and returns – this keeps profits up in the short term but through currency devaluation not quality gains combined with the resultant shift in price that this would bring about.

Growers face a situation of more money going out than coming in and the mantra becomes that wine prices must rise. Blissfully wishing away the bottom end of the market is not realistic, however. Rational consumer behavior is to acquire the best quality for the least amount of expenditure and South African producers should embrace this.

For the South Africa wine industry to survive it must undertake a two-fold process: 1). reduce in volume the lower 60% of its business (this already underway given the decline in the national vineyard over the last decade) and 2). ameliorate what it does produce – presuming that markets are more or less efficient, the reason producers don’t get more money is because buyers don’t value it sufficiently. Producers need to move from bulk to large brands which sell initially in the affordable market segments and then as more margin is achieved, the necessary cash will become available to finance the establishment of new markets.

Next, I would contend that the vast majority of international consumers don’t view South African wine as cheap ‘n cheerful but rather have no conception of it all.

Some might argue that what therefore needs to be done is to this persuade sophisticated consumers that South Africa’s top wines are worth the kind of money many are willing to shell out for the best of France, Italy and Spain and that they way to do this is by raising the profile of site – Cabernet Sauvignon wedded not just to Stellenbosch, but to the Simonsberg, and not just to the Simonsberg but to Kanonkop, for instance, and of course this can do no harm – it will in a small and very gradual way will win over the elite.

In a similar vein, many will point to the stir that the New Wave headed up by Eben Sadie and co. has caused among international wine geeks and their achievements are not to be overlooked. However, relying a small band of independents to sway the opinion of the vast majority of international consumers is frankly ludicrous. These avant-garde producers, along with the better run estates and private cellars, are probably commercially secure, the issue of land tenure notwithstanding, but what we also desperately need is a strongly branded wine businesses operating at the entry level and middle tiers of the global market.

To the extent that the industry has succeeded in the modern era, this has been due to a combination of mid-sized brands and personality-driven initiatives (Bruce Jack of Flagstone and later Kumala as well as Charles Back of Fairview and Spice Route both come to mind) and these surely show the way. Brands bring margins and margins equate to marketing budgets and only then can the story of South Africa wine be properly told.

Many lay claim to the title of “influencer” but media personality Bonang Matheba is the real deal with 2.6 million followers on Instagram and 3.43 million on Twitter. Her latest foray into retail sees her launching two examples of Méthode Cap Classique under the House of BNG label, a Brut and a Brut Rosé, the wines made by Jeff Grier of Villiera and available from Woolworths for the not inconsiderable sum of R399.99 a bottle each. Tasting notes and ratings as follows:

House of BNG Brut Non-vintage

Straw yellow in colour. Apple, peach and some yeasty character on the nose. Rich, full and not unduly sweet on the palate. Tangy acidity plays off against a fine mousse. Perfectly respectable if not super-complex.

Editor’s rating: 87/100.

House of BNG Brut Rosé Non-vintage

Coppery pink in colour. The nose shows strawberry, Turkish Delight and some earthiness. The palate is rich and broad with a creamy mousse. Inoffensive but a bit flat and short.

Editor’s rating: 86/100.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

Urbanologi restaurant, at the 1 Fox Precinct in the Johannesburg CBD, is housed inside a recently renovated, late 19th century warehouse. So stylish is the building conversion that it won best hospitality venue in Africa and the Middle East at the 2017 International Restaurant and Bar Design Awards. Legend has it that the first telephone call on the Witwatersrand was made from within its hallowed halls. And now the space (which is shared with Mad Giant craft brewery) is hipster central with iPhone toting types at every table.

Executive chef Jack Coetzee has designed his menu in line with a food philosophy he calls Project 150 whereby he is attempting to source all ingredients within 150km of the restaurant. His aim is to “engage with conscious living and seasonal, sustainable practices around food.” Every menu item is listed with the name of the farm from whence the core ingredients came and the distances required to put them onto plates. Coetzee also has a zero-waste policy so, wherever possible, scraps and offcuts are transformed into other edible offerings.

In truth, not everything served fits the project 150 guidelines. The restaurant uses sugar, flour, spices, chocolate, tea, coffee, wines and spirits that are not produced locally but it seems mean-spirited to pick on the few things that aren’t hyper-local when almost all Urbanologi’s competitors are binging on imported and unseasonal stuff. This is a sincere, and mostly successful, attempt to reduce the menu’s carbon miles.

Portions are small but reasonably priced and the menu is designed with share-share, mix and match across the table type meals in mind. My friend and I enjoyed a delicate duck liver parfait (R45) made with the organs of birds who had previously resided in Delmas (62km from Urbanologi). The accompanying brioche bread was enriched with surplus duck fat (rather than the traditional butter) in line with the zero-waste approach. The beetroot-cured trout sashimi (R95) was from fish farmed in Midrand. At 82km and 92km respectively, the Clydesdale grilled asparagus with goats’ cheese (R105) and cumin-infused Bapsfontein lamb belly (R110) had travelled the furthest to feed us.

Pastry chef Mmathari Moagi’s guava mimosa with lemongrass sherbet (R60) had a remarkable, soothing clarity of flavour. Her poached fig and ricotta mélange (R60) was an exquisitely articulate elegy to the loveliness of late summer. The accompanying coffee-ground tuile biscuit gave textured crunch to the fabulous figs and a second life to what would otherwise have been discarded espresso bi-product.

Urbanologi is well worth a visit and the gripe that follows is a direct result of the team being good. There is a tendency to let mediocre chefs off the hook but faced with skilled, thoughtful and ambitious artists like Coetzee and Moagi, I want them to be better. Because I know they can.

Perhaps I also turn into a language pedant but as I understand it any ‘ology’ (even if spelt with an i) is the study of whatever precedes it. So, Urbanologi should be the study of the urban space in which the restaurant sits. And it is not. The generic industrial-chic interior ticks all the international hipster boxes of exposed pipes and faux graffiti murals but it also has floor to ceiling windows looking out onto Johannesburg Central Police Station and what remains of the city’s first Chinatown. The noodle bar at which George Bizos and Nelson Mandela ate as article clerks is literally a stone’s throw from Urbanologi’s parking lot. The window from whence Ahmed Timol was pushed is right there. There are plenty of Asian fusion elements on the menu but they are all the same Asian fusion frills that one would find on plates in Paris or New York. Johannesburg’s epic Afro-Asian Diaspora experience and flavour repertoire is entirely absent.

Cut to 2019 and there are Mozambican bajias (bean fritters) and Zimbabwean munyemba (cowpea leaves) for sale on every CBD street corner. Zulu ujeqe (steamed bread) vendors compete for customers with Ethiopian injera fermented flatbread makers. ‘Hardbody’ heritage chicken dominates the street food space. Almost all of the above is made from ingredients grown or reared in Gauteng. Much of it in the inner city. The hedges that surround many of the government buildings are grown out of indigenous amatungulu (Carissa macrocarpa) bushes full of foragable fruit. All of the above is invisible at Urbanologi.

The truly, madly, deeply, unique and potentially delicious wonder that is the Johannesburg city centre has been ignored. Urbanologi is a good restaurant. In order to be a great one, the chefs need to go outside and engage with where they actually are.

Urbanologi: 011 492 1399; 1 Fox St, Ferreiras Dorp, Johannesburg; urbanologi.co.za

In one of those nice coincidences, the evening before the winners of the Cabernet Franc Challenge were posted I had been drinking an older vintage of one of the least known of the gold-medal winners. Talking of which, there do seem to have been an awful lot of medals awarded. There were a “top six” wines as well as 19 golds for the monovarietal cab francs (see here). Unfortunately – and surely it’s a problem? – there’s no publicly available info that I can find about the ranking protocol, nor about how many entries there were; but putting 25 wines into your top category surely implies somewhat over-generous judging of a small category like cab franc. That impression of over-generosity is for me made more acute when I look at many of the winners, but still.

I say “top category”, but in fact, the gold medal winners are the only names I can find. The competition seems to be run/owned by a marketing person (Cobie van Oort) and it’s a clever move to only list high winners, if somewhat disingenuous: wineries don’t like seeing their wines listed as low-scorers, and judges are also frequently embarrassed when complete lists are published, allowing for people to make comparisons.

Oh, and there were also four triumphant wines in the vintage category: a winner and three golds. Of these four, one was reasonably enough from 2011, the other three from 2014 – which, as someone commented on this website, “Five years is not nearly enough time to test a wine’s proper longevity and ability to mature with benefit”.

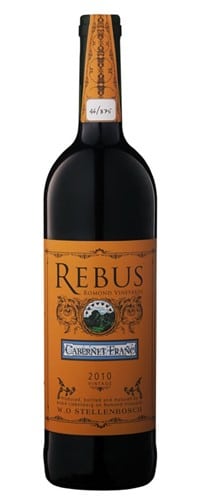

Anyway, in the usual run of events I doubt if I would have bothered to find this all out (or even read the report on this website), as this usually seems to me one of the more suspect of the rash of wine competitions – though it does attract a number of respectable cab franc producers. But, as I say, I’d been drinking a mature local cab franc, and been in two minds about it, so I looked to see if it featured. And there it was among the golds: Rebus Cabernet Franc 2015 from Romond Vineyards, a later edition of the 2010 I’d had the night before (and which should have done quite well in the Vintage class if it had been entered – I’ve no idea if it was). I rather think, in fact, that the 2015 was the first released since the 2010. The winery website offers 2010 as the current release, and it was the one I tasted for the Platter’s Guide prior to the 2015 I tasted last year – both of them rating 3.5 stars, incidentally.

Last year, winemaker-owner André Liebenberg also sent me a bottle of the 2010 to try again, but I confess that in the welter of Platter bottles it got put aside and I only recently rediscovered it. I was quite impressed by the wine and its development over nine years, and wondered if I had slightly underrated it previously. Not really the style of wine I most enjoy, being big, ripe and bold, with plenty of oaky power, and some alcoholic/oak sweetness and heat on the finish. But the years had harmonised all those components somehow. I also didn’t notice as much as I had previously done the strongly herbaceous element – something that had also disturbed me in the 2015, a wine of generally similar character.

Last year, winemaker-owner André Liebenberg also sent me a bottle of the 2010 to try again, but I confess that in the welter of Platter bottles it got put aside and I only recently rediscovered it. I was quite impressed by the wine and its development over nine years, and wondered if I had slightly underrated it previously. Not really the style of wine I most enjoy, being big, ripe and bold, with plenty of oaky power, and some alcoholic/oak sweetness and heat on the finish. But the years had harmonised all those components somehow. I also didn’t notice as much as I had previously done the strongly herbaceous element – something that had also disturbed me in the 2015, a wine of generally similar character.

Romond Vineyards is a small property, growing Bordeaux red varieties and pinotage on the lower slopes of the Helderberg in Stellenbosch – not far from where Chris Keet made some excellent cab franc-based wines for Cordoba (in a rather different style). So it’s not surprising that the fruit quality of the Rebus wines is impressive, as evidenced by the development of the 2010, which still has plenty of life in it. If you enjoy wines like this, you could do much worse – though the asking price of over R1100 is a trifle steep. The Fanfaronne blend with cab sauvignon and merlot seems to me the better wine and is a quarter of the price. It also won a gold medal on the Cab Franc Challenge, by the way. The label, as you can see is striking and attractive – though I suspect that if Veuve Cliquot noticed, they’d protest, as they tend to believe they own that colour.

This is categorically the best bottle-fermented sparkling wine I’ve ever drunk from South Africa and given who it’s made by, it comes as no surprise. Pieter Ferreira, after starting his career at Haute Cabrière and then becoming a long-serving key player at Graham Beck, now also has his own label.

Grapes from Darling and Robertson, lees contact lasted five years. Yellow-green in colour, the nose is captivating with green apple and lemon, some smoky reduction that totally suits the wine plus some brioche and ginger. The palate – pure fruit, fresh acidity, fine mousse and a very long finish. Intensely flavoured and properly complex. Dry but not excessively austere. So, so precise. Alcohol: 12.22% and RS 3.86 g/l. Approximate retail price: R430 a bottle.

Editor’s rating: 94/100.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

The TOPS at SPAR Wine Show – Durban takes place The Globe at Suncoast from 9 to 11 May. Taste, buy and attend wine theatres to learn more.

The TOPS at SPAR Wine Show – Durban takes place The Globe at Suncoast from 9 to 11 May. Taste, buy and attend wine theatres to learn more.

Some of the best work from this year’s Wine Label Design Awards convened by winemag.co.za and sponsored by Rotolabel will be on display and you can vote for your favourite.

You can also:

Win one of five sets of double tickets worth R385 each. To enter, all you have to do is 1) sign up for our free newsletter and 2) like our Facebook page.

To subscribe, click HERE.

To visit our Facebook page, click HERE.

Competition not open to those under 18 years of age and closes at 17h00 on Friday 3 May. The winner will be chosen by lucky draw and notified by email. Travel and accommodation not included. Existing subscribers are also eligible.

To buy tickets, click here.

There were nine sign-ups and The Wine Show was glad to provide all with tickets. These were: Trevor Allnutt, Suzanne Davis, Paul de Kock, Pam Govender, Rudi Hahn, Deshnee Naidoo, Bhavana Singh, Hamish Singh and Indrin Venketsamy.