Talking of Tim Atkin and his high scores (we were, weren’t we?) … I had the privilege of attending his tasting of 158 (of the 160) wines he scored at least 95 points for his 2018 Special Report. His preface to the tasting booklet described it as “the most amazing line up of South African wines ever assembled in one place”.

Talking of Tim Atkin and his high scores (we were, weren’t we?) … I had the privilege of attending his tasting of 158 (of the 160) wines he scored at least 95 points for his 2018 Special Report. His preface to the tasting booklet described it as “the most amazing line up of South African wines ever assembled in one place”.

I’m pretty sure he’s correct. There were, for example, twice as many wines (and I can’t think of any that weren’t good) as there were at the last Platter five-star tasting. And if a tiny asteroid had happened to pick on the Delaire Graff wine cellar – where the event was taking place – it would have disastrously wiped out the best of South Africa’s winemakers as they poured their wines (and participated in the gossip and chat that’s a vital part of the pleasure of occasions like this).

As I wandered around I was guilty of envy. Envy of Tim Atkin. And, though I risk the boringness of raising one of the recurrent, inevitable debates in modern wine commentary, I’ll tell you why. I’d just come through a lengthy process of tasting wines for the Platter guide, according to the curiously hybrid Platter methodology: first, all the wines tasted at home, at leisure and with access to all possible information about the wines; then the wines put forward by the team of tasters as five-star nominations (plus those scoring close to the magic 95-point mark) tasted blind by panels of three.

What I’ve envious of is Tim Atkin making his judgement entirely on a sighted basis, without the lottery element that is inevitably part of a biggish line-up of wines judged blind and quickly (though, as I’ve said before, the methodology for the Platter final tasting is about as good as it can be). I suppose another enviable part of Tim’s report is that it expresses the aesthetic and skill of a single taster, whereas as the Platter team inevitably have differences of preference and ability that get expressed in their judgements.

I’m not permitted to say anything about this year’s work for Platter until the Guide is published in November, but the basis for my envy of Tim’s sighted-tasting protocol is apparent in previous Platter results. It’s not so much the sins of commission that have worried me in Platter five-star listings, as mostly the awards go to sufficiently plausible wines. It’s the sins of omission. This problem is partly signalled by the comparatively small number of 95+ pointers in Platter, compared to the Atkin Report: my worry is the great wines that slip away through the blind panel tasting. I’ll cite just one example of many in the last three years of Platter scores: for the splendid range of Alheit white wines, in the 2016 Guide – no five stars; 2017 – two; 2018 – one.

It’s not unreasonable, in my opinion, to question the procedures of a guide with that sort of hole in it. But such errors – if you admit that’s what they are – are inevitable in biggish blind line-ups, I fear, however hard one tries to avoid the problem.

I thought it would be interesting, in this light, to compare the results in Tim’s Report with those in the 2018 International Wine Challenge, of which he is co-chairman – and which he claims to be “the world’s most rigorously judged blind tasting competition”. Despite vintage differences, I managed to find comparisons to justify my contention – and my envy of Tim for his “sighted tasting” protocol for his Report.

Certainly there are some positive correlations: the four South African IWC trophy winners did rate 94 or 95 in the Atkin Report (by Tim’s subsequent sighted judgement). But, as I say, it’s the holes that are the telling thing. And I noted a few KWV winners of mere bronze medals at the IWC scoring 95 in the Report: Perold Tributum 2014 and Mentors Petit Verdot 2016. There are quite a few with one medal-placing difference, up or down (entrants achieving less than “Commended” status are not named; and as no actual scores are given for the IWC one can’t see precisely how significant the differences were). Also obviously relevant, and drastically reducing the scope of comparison, the overwhelming majority of South Africa’s top producers don’t enter the IWC.

There might well be other problems in the way Tim judges wines for his Report – I suspect the wines are not all judged in the same way, for example, with some tasted at leisure with the producers, others rapidly in big line-ups – but it’s an impressive document with a thoughtful introduction, and for what it’s worth I agree with his judgements probably more often than not (when I have tasted the wine, or the same vintage, which is far from all the time). My envy remains, that he can take his sighted judgements all the way through. The report is available for GBP 20/ZAR 395 from Tim’s website.

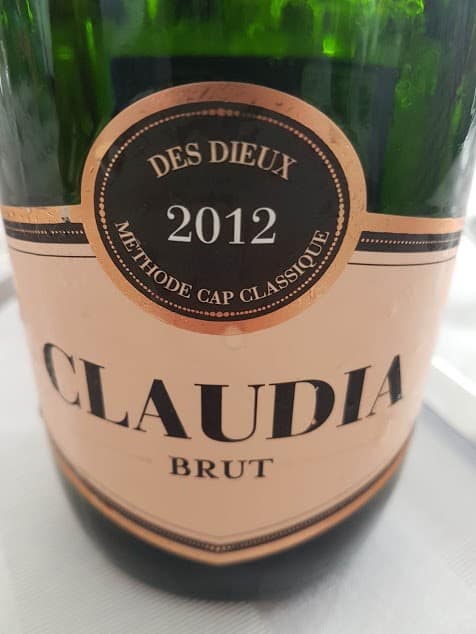

Domaine des Dieux Claudia Brut 2012

There were a total of 127 entries in this year’s annual Amorim Méthode Cap Classique Challenge, results as follows:

Best Brut, Overall Winner:

Domaine des Dieux Claudia Brut 2012

Best Blanc de Blanc:

Colmant Brut Chardonnay N/V

Rosé:

Simonsig Woolworths Pinot Noir Rosé No Sulphur Added 2016

Best Museum Class:

Pongrácz Desiderius 2009

Frans Malan Legacy Award:

Christine Rudman

Ian Naudé is another champion of old vines, his recently released Semillon 2016 made from vines between 35 and 55 years old, 60% from Durbanville and 40% from Stellenbosch. On the nose, some floral blossom, before blackcurrant and tangerine. The palate shows dense fruit, tangy acidity and some nice grippiness while the finish is long and salty. Alc: 12%. Price: R280 a bottle.

Editor’s rating: 93/100.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

Twenty wines have been shortlisted as finalists for 2018 FNB Sauvignon Blanc Top 10 honours. The contenders, in alphabetical order, are:

Twenty wines have been shortlisted as finalists for 2018 FNB Sauvignon Blanc Top 10 honours. The contenders, in alphabetical order, are:

Bellingham Homestead 2018

D’Aria The Songbird 2017

Darling Cellars Reserve Bush Vine 2018

De Grendel Koetshuis 2017 (wooded)

Delaire Graff Estate 2018

Diemersdal Winter Ferment 2018

Flagstone Free Run 2017

Fryer’s Cove Doringbay 2017

Hidden Valley 2017

Iona 2018

Kleine Zalze Vineyard Selection 2017

Kleine Zalze Zalze Vineyard Reserve 2017

Marianne 2017 (wooded)

Nitida Wild Child 2017 (wooded)

Nova Zonnestraal Constantia Royale 2018

Rietvallei 2018

Rustenberg 2018

Strandveld Vineyards Pofadderbos 2017

Tokara Reserve Collection Elgin 2018

Windmeul Kelder 2018

Results to be announced on 10 October.

“Are wine writers losing touch with the people that actually buy wine by spending too much time navel gazing?” was one suggestion put forward when I recently requested a topic for a column via Twitter. Well, it would be disingenuous to pretend that senior wine writers don’t have it good. Kanonkop Paul Sauer 2015, rated 100 points by Tim Atkin MW in his recent South Africa Special Report, has an approximate retail price of R600 a bottle. And the likes of Alheit Huilkrans Chenin Blanc 2017, Lismore Reserve Syrah 2017 and Vin de Constance 2014, all rated highly on this site, don’t come cheap and yet if you’re in with the in-crowd, these flow pretty freely. These might not be “cheap” in a global sense (we’ve heard the mantra that “SA fine wine is too cheap” quite a lot recently) but they’re expensive if you’re earning rand and stocking your own cellar.

Let’s say you’re a proper wine enthusiast who’s happy to open a bottle in the vicinity of R150 to share with your sweetheart on week nights (Flotsam & Jetsam Chenin Blanc, effectively Alheit’s second label, is around that price) and then two bottles of really special stuff at the weekend at R300 a bottle (Rocking Horse from Thorne & Daughters will set you back some R250 while Aristargos from David & Nadia more like R340). That equates to a weekly wine bill of R1 350 and a monthly wine bill of R5 400. Which means you have to be earning quite a lot of money before tax to afford such a habit.

But I think it’s not just that wine is an expensive pursuit but rather that it is a field of interest that doesn’t really encourage irreverence. When I started out in wine writing, I wanted to be the next Lester Bangs (the rock critic who was at the height of his powers in the 1970s) rather than the next Robert Parker or Janics Robinson. As with rock, the wine scene (or at least the part I was interested in) seemed to be populated by the anti-establishment, non-conformist, off-beat. The then very much outspoken André van Rensburg had just joined Vergelegen and the revolutionary Eben Sadie was about to leave Spice Route to start his own label…

What happens with wine, however, is a lot of one-upmanship and I think most critics are guilty of this. They are constantly trying to outdo their colleagues and almost inevitably end up outdoing their readers. Knowledge is important if you’re going to pass judgement but the ability to engage seems absent all too often.

Lester Bangs’s first piece was a negative review of the influential hard rock band MC5 that appeared in Rolling Stone magazine in 1969. “Musically the group is intentionally crude and aggressively raw. Which can make for powerful music except when it is used to conceal a paucity of ideas, as it is here,” he writes, which is just such a terrific put-down.

It made me think about always controversial “orange” or skin-fermented wine and I wondered who at work in the world of wine has anywhere near the same turn of phrase. Where you to write something similar of a clouding bottling under some local hipster label today, you would most likely be met by the reaction: “Ah, but you haven’t drunk enough from the Jura to comment”. Sure, Bangs had an encyclopedic knowledge of music but he didn’t let it get in the way of a visceral reaction.

Robertson property De Wetshof makes an array of high-quality examples of Chardonnay every year but the other Burgundian variety which is Pinot Noir proves a more difficult proposition, 2017 being the first vintage to see commercial release since 2013.

The nose is particularly engaging with notes of red cherry, rose water, musk and some pepper while the palate is marked by sweet fruit, vibrant acidity and fine tannins, the finish long and gently savoury. Generally speaking, a rather pretty take on the variety. Price: R315 a bottle.

Editor’s rating: 90/100.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

‘At the Rondebosje, the vineyard is flourishing lustily,’ wrote the fourth commander of the Cape, Jacob Borghorst, in a despatch to the Lords XVII on 14 June 1669.

It might seem unbelievable that Rondebosch, in the heart of Cape Town’s southern suburbs, was once the centre of winegrowing in South Africa, but it’s a fact.

Jan van Riebeeck first planted land near ‘het Ronde Doorn Boschje’ experimentally in May 1656, and he reserved it for a new Company’s Orchard in 1657, when plots were granted to the first vrijburghers along the Liesbeeck River. To the south was the Company’s large granary (Groote Schuur) and to the north was Hollandsche Tuin, a communal property where the Cape’s first ‘famous’ winemaker initially farmed alongside Steven Botma and two other men.

Today Rustenburg Girls’ Junior School and much of the University of Cape Town stand on what was once the Company’s Orchard – later known as Rustenburg. The land with its ‘excellent pleasure-house’ for hosting ranking officials was developed during the 1660s, and by 1673, the Cape’s sixth commander, Isbrand Goske was able to report that wine production at Rustenburg had increased to five leaguers (11,260 litres), excluding what was still on the lees.

By 1684, when tenth commander Simon van der Stel had chosen to live at Rustenburg (situated conveniently on the main road that led from the Castle to False Bay and Hout Bay), he estimated that 100 leaguers of wine could be expected in a good year from the 100,000 vines planted there.

Van der Stel, famously, knew a thing or two about winegrowing, having owned two vineyards at Muiderberg in the Netherlands where he had personally made wine and brandy. Finding a great deal of the vrijburghers’ wine to be ‘disgustingly harsh’, he soon imposed penalties for unripe grapes and dirty barrels. Above all, though, he set out to teach the vrijburghers by example…

As we all know, he managed to have an inordinately large piece of land granted to him on 13 July 1685. Named Constantia, this would eventually become his ‘model farm’. However, Van der Stel’s focus to a very great extent, right up until his retirement from official Company affairs in 1699, was Rustenburg.

It was here that he conducted a number of experiments, such as planting ‘Persian’ vines from raisin pips in 1687. It was here that he also reported on various viticultural problems, from ‘a large kind of locust, whose like has never been seen here before’ in 1696 to vine disease in 1697: ‘The bunches hung without berries on the stocks, and the grape was very black, spotted, and poor.’

1698 saw the start of a six-year drought, leaving many wine farmers ‘much injured’ – and here it’s important to note that Rustenburg wasn’t an anomaly as far as winegrowing along the Liesbeeck River was concerned. The December 1692 Opgaafrol or tax census showed that Cornelis Botma, farming next door to Rustenburg at Zorgvliet, had 16,000 wines planted, while Jan Pietersz Louw had 20,000 wines on his farm, Louwvliet (today incorporating the Newlands Rugby Stadium), as did Albert Gildenhausen slightly to the north, while Jan Dirksz de Beer to the south had 25,000 vines, and the new owner of Bosheuvel, Guillaume Heems, had 40,000.

In fact, there were 303,000 vines being grown by 34 wine farmers in the Cape District according to the 1692 Opgaafrol, which showed that Stellenbosch had 233,200 vines (divided among 48 wine farmers) while Drakenstein – stretching between Wellington and Franschhoek – had 197,000 vines (between 60 wine farmers, most of them French Huguenots who’d arrived from 1688 onwards).

By 1716, there were 1,271,000 vines planted in the Cape District compared to 1,105,000 in Drakenstein – and yet the Cape District produced only 610½ leaguers that year compared to Drakenstein’s 940 leaguers.

This may say something about growing conditions being tougher along the Liesbeeck River than the Berg River, or it may say something about quality versus quantity.

Certainly Liesbeeck winegrower Johan Daniel Wieser of Westerfoort had a lot to say about quality versus quantity decades later, in 1779, when a number of wine farmers petitioned against the tough conditions under which they then ‘groaned’ (lack of free trade, heavy taxation, the low prices paid for their wines by the Company cellarer…).

Westerfoort, later anglicised to Westerford, was a farm originally known as Wijn en Brood (‘on account of its fertility’) when Van der Stel’s friend and business partner Johannes Pfeiffer owned it in the early 1700s. It was here, not at Constantia, that Van der Stel died on 24 June 1712. Meanwhile, Wieser had grown up on the 1716 sub-division of Constantia known as Groot Constantia: his father Carl Georg Wieser had owned Groot Constantia from 1734 until his death in 1759, making the ‘delicious, scarce and expensive’ Constantia wine written about by German architect Johann Wolfgang Heydt in 1741. The illustrious property had then been transferred to Wieser Junior’s step-brother, Jacobus van der Spuy, and in 1779 it had come into the hands of Hendrik Cloete.

‘Our wine nearly equals that of Constantia,’ wrote Wieser in 1779. ‘Our vineyard has 100,000 vines, which gives us from 40 to 50 leaguers, while the Paarl-Franschhoek vineyards give 100 leaguers per 100,000 vines. They irrigate their vineyards, which give much must but bad wine. We mature our grapes till they are almost raisins and our wine is consequently of a good quality and not to be sold at the miserable price the cellarer offers.’

Of course some of the Franschhoek wines must have been ‘of a good quality’ too. The point is that, today, it’s not easy to imagine 100,000 vines growing on land that now includes Westerford High School and the South African College Schools (SACS), stretching up to the mountain and producing wine deemed not much inferior to the already world-famous Constantia.

And Westerford was just one of many large farms along the Liesbeeck – farms that, over the next two centuries, would give way to housing, churches, shops, offices, sports grounds, schools, a university, a railway line and an extensive road network: in short, the southern suburbs of Cape Town.

Bibliography

Leibbrandt, HCV: Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope (Letters despatched, 1696-1708), originally published by W.A. Richards & Sons, 1896-1905, digitised by University of California Libraries

Leipoldt, C Louis: 300 Years of Cape Wine, Tafelberg, 1974

Theal, George McCall (ed): Abstract of the Debates and Resolutions of the Council of Policy at the Cape from 1651—1687, Cape Town, 1881

Van Rensburg, J.I: Die Geskiedenis van die Wingerdkultuur in Suid-Afrika tuidens die Eerste Eeu, 1652-1752. MA Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, 1930

Spring’s arrival has seemed rather more convincing in the Western Cape the last few days, with sunny skies and warm sunshine. The vineyards have known change for a while now, the dead-looking vines thrusting out those tight handfuls of fresh green leaves that look somehow sticky. The drought seems to have been broken – though farmers whose vines suffered most are still unsure whether the vineyards will have recovered sufficiently (those that didn’t succumb entirely) to produce a decent crop in 2019.

But Stellenbosch didn’t suffer too much and everything was looking fresh, hopeful and eager for the future last Saturday morning when I visited Ginny Povall’s Devon Valley farm, Protea Heights. As we walked up between vineyards and protea plantations, the views were lovely enough to make obvious answer to a question why Ginny sunk her dollars into this farm back in 2008 (she was not long previously a serious player in New York corporate life). It was then producing only proteas for export, and that’s still a vital part of it, more lucrative than the wine; there’s also a guesthouse, but I think it could be said that Ginny’s heart is not really in that. It’s really in growing and making wine.

She’s best known for her Mary Delaney Collection (known as Botanica till that was challenged – she decided not to fight, and keeps Botanica as the overall name, and flowers as a general theme on the labels). Her fine Chenin Blanc from the Citrusdal Mountain area now loosely known as the Skurfberg is famous, in a quiet way. She was, incidentally, the first wine producer to have a contract with a farmer up there, beating Anthonij Rupert and Eben Sadie to it: her maiden vintage was 2009 (it got five stars in Platter), the same as OuWingerdreeks Skurfberg and Cape of Good Hope Van Lill & Visser Chenin Blanc.

The Mary Delaney Range has grown in scale and renown since then, though its presence in the local market is more muted than it should be – Ginny admits she has not been the greatest of marketers. There are now also a pair of Hemel-en-Aarde pinots, a semillon from Elgin, and the Fire Lily Straw Wine from Stellenbosch viognier. She makes them all in the Zorgvliet cellar, but hopes to soon move at least the red winemaking to the home farm.

The wines in Ginny’s Big Flower range are especially important to her, however. They come from her own five hectares of vines, which she started planting in 2009: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, cab franc and petit verdot. (“No malbec”, she said decisively, but I neglected to ask why.) Incidentally, I’ve never seen cab sauvignon planted in the way some of it is here, designed to cope with a fairly steep slope: fairly densely spaced, basically as goblet-shaped bush vines, but each with its own pole, to which the shoots are grouped and tied: echalas in French, stok-by-paaltjie in Afrikaans (and irritatingly wordy in English).

Ginny gave me three vintages of her Merlot to taste. The maiden 2014 I liked immensely. Not at all a light wine, but quite fresh and rather elegantly balanced, with a firm tannic structure. Serious, proper wine. The 2015 is bigger and riper and more voluptuous – partly vintage, I suppose, but also reflecting Ginny’s confessed “conflictedness” about style. Her American importer prefers wines like this, but she doesn’t and seems set to keep rather more restrained. Only old oak used, which helps keep the wine from blockbusterdom. But the 2015 is a good wine – it bears a “93 points” sticker from Tim Atkin, so he thinks so too. The 2016 (bottled but not to be released for a while) is delicious and spicy-savoury, in the more refined 2014 mode, I’m pleased to say. (The 2015 doesn’t seem widely available, but I see it for R170, and other Big Flower wines, on Port2Port.)

The Cab has been around since 2008, but the first from home grapes was 2014. The 2015 is a very good expression of the variety, also matured in older oak, with a very good tannic-acid structure but not quite up to the Merlot 2015 in balance, I think, and a little too obviously ripe and sweet for my taste. There’s also a Cab Franc, also in the riper, big style, but less successful than the other two varietal wines. The grapes all come together in the Aboretum blend, made up of selected barrels (some of them new oak). Unfortunately our bottle of 2014 was not at its best, but the 2015 (43% cab) showed well – more restrained than the other 2015s, with a drier finish; savoury, well structured and balanced.

So far it’s looking as though merlot is the star performer of the farm. But the vines are maturing and so is Ginny’s confidence and skill with vinifying the Bordeaux varieties – unsurprisingly, given her well established flair with white grapes and pinot. I think she’s hankering after lighter, fresh and elegant wines, and I much look forward to them.

Upper Bloem Restaurant is genuinely special. The food is elegant and delicious; the food story is intelligently told. This is a restaurant that enriches the diner’s experience of being in Cape Town – whether resident or tourist.

Upper Bloem Restaurant is genuinely special. The food is elegant and delicious; the food story is intelligently told. This is a restaurant that enriches the diner’s experience of being in Cape Town – whether resident or tourist.

Try this mouthful: pickled aubergine and caramelized onion served in a baby onion shell. The dish smokes at the table. It smells like the coals used for braaiing kebabs on the Bo-Kaap streets. The edges of the onion are charred. The spices are reminiscent of bobotie; the aubergine is velvety-smooth; the caramelized onion is chutney-sweet. A single pomegranate jewel pops on the tongue; a dab of goats’ milk yoghurt calms the whole.

Upper Bloem is inspired by head chef Andre Hill’s childhood in the Bo-Kaap; specifically Upper Bloem Street, where he lived. But Upper Bloem Restaurant goes beyond biryanis and bredies: Hill and chef patron Henry Vigar have developed a menu that embraces the British Sunday roast, Dutch street food and Persian feast dishes. The menu also links the Bo-Kaap to the coast, with seaweed butter and smoked snoek pâté. Eating at Upper Bloem takes you back a hundred years, to the formative years of Cape Town cuisine.

Chef patron Henry Vigar told me Upper Bloem wanted to do something different with the concept of terroir. “Wine farms can offer a terroir experience with ingredients grown right there on the farm,” he said. “We want to offer a terroir experience in an urban environment.”

Upper Bloem serves six sharing plates for lunch and nine for dinner. The dishes arrive in three “waves”. Wine pairing is optional, as are the bread board and desserts.

On the bread board, the garlic roti is buttery and flaky like the Cape Town flatbread you’d use for a salomie, not like a chewy Indian roti. The garlic is an evocative addition; it recreates the taste of garlic bread off the braai. The teriyaki glaze, piped around the exquisitely balanced snoek pâté, adds an Asian edge while referencing South Africa’s favourite sweet-and-sour peach chutney. The samoosa crisp is flour-dusted. The whole fennel seeds in the crisp bring to mind Indian after-dinner sweets.

The Boerenkaas croquettes are masterfully cooked. This is one of the dishes that gives the small plates menu here a global feel. The croquettes reference not only tapas, but also Dutch cheese and apples.

Upper Bloem Restaurant’s is seasonally inspired. One of the dishes in the second “wave” utterly transformed one of our humblest winter staples. The roasted butternut with coconut “soup” and roasted seeds tasted like beef fillet and gravy. This magic was likely achieved by very low, very slow roasting of the butternut. The crunchy, oily seeds worked like roasted meat fat and the coconut was seasoned so as to enhance the richness of the “soup” while pushing back the sweetness.

The beef carpaccio, served alongside the butternut, tasted like a cross between an Italian starter and a roast beef dinner. The pickled mushrooms lent a Mediterranean lemony-ness to the dish. They pickles also tricked me into tasting horseradish in the roasted beef mayonnaise.

Vigar is an extremely accomplished, British-born chef. He has been chef patron at La Mouette in Sea Point for eight years. He chuckled when I told him I could taste English roast dinners in the Upper Bloem menu.

Vigar is inspired by his collaboration with Hill, who joined him at La Mouette as a sous chef in 2013. Hill was “a young, exceptional Cape Town local”. Last year, Vigar invited Hill to co-create and co-own Upper Bloem.

On the Upper Bloem menu, Hill is quoted as saying that what he’s cooking now “feels like coming home”. He hopes that “what we’re doing will make other chefs from Cape Town proud of their food and their abilities”.

Hill and Vigar agree it’s their “vastly different backgrounds” that makes “their culinary co-creations so interesting”.

The lamb neck biryani is a masterclass in how to honour heritage. The Persian origin of the dish is evident in the jeweled appearance of the dish: the ruby pomegranate seeds; the emerald-hued curry leaves; the golden, deep-fried onion petals and soil of candied black rice. At first glance, this is a feasting dish; a dish fit for royalty. But hidden beneath the rice and spice mix is a surprise: lamb neck. This is a humble cut. The way the meat is cooked makes it tender, glossy and deep with flavour.

This is how Upper Bloem brings history and comfort together. Each of the sharing plates here is confident, intelligent and authentic. This establishment is bound to become a standard-setter for heritage food and regional cuisine.

For dessert, there’s a choice of frozen naartjie curd with curry leaves – a charming, looky-likey dish – “koe-sisters” with coffee cream and caramelia apple and nut clusters.

Hill and Vigar admit to evoking “nostalgia”, but there is nothing old-fashioned about Upper Bloem Restaurant.

The décor is modern and colourful: the chairs and benches are upholstered in shades of turmeric and nutmeg. The pastel blue in the colour scheme pops like Bo-Kaap house paint. The tiled walls resemble the patterned hallway floors of Victorian homes. The crockery is handmade – the jade glaze on brown clay makes the plates look like river stones.

The diners here were anything but fuddy-duddy. Our fellow patrons were food enthusiasts. They’d have to be. It was raining out, on a cold Wednesday at noon.

One woman strode in alone. “I’ve seen so much about this place on Instragram,” she gushed. “I had to try it.” Later, her eating companion entered in a pair of voluminous African print trousers and a bubblegum pink beanie.

Another pair consisted of a photo-taking lady with an “it” fringe and a man with a egg-beater tattooed on his forearm.

Two older ladies sat quietly in the strip of seating opposite the open-plan kitchen that reminded me of New York restaurants. They reminded me of New Yorkers too, in their woollen coats, with their good handbags.

The table alongside us were restaurant industry types. They gushed to chef Vigar about the triple-cooked potatoes served in curry sauce. This dish, served alongside the biryani, is another example of a successful culinary mash-up: this time, roast potatoes and homely potato curry are the inspiration. The curry is elevated by the addition of Muizenberg sour figs and burnt chard.

The service staff were warm and friendly: homely, in a word. The manager set the tone with her efficient, motherly air. The staff’s lack of pretension was refreshing. Everyone who served us was knowledgable but unobtrusive. It’s important, when there are six dishes, to let the food do the talking. No-one wants to be robbed of their dinner conversation time by an over-wordy waiter.

Having chef Henry Vigar visit the tables after lunch firmly established the homely atmosphere. All the patrons seemed to welcome the opportunity to chat. I can imagine that for tourists having their meal bookended by a welcome from the manager and a chat from the chef would remind them of the human stories behind their food.

Vegetarians are accommodated here. My companion’s snoek pâté was replaced by a pumpkin pâté that was flavoured like a samosa filling. Instead of the beef carpaccio, she had a pickled mushroom dish served on Asian crackers. Roasted cauliflower was substituted for lamb neck in her biryani.

The wine list is confidently short. The nine-plate dinner may be paired with a trio of wines and a dessert wine. Wine is sold by the glass. The portion is generous, served in a carafe. A request for a jug of tap water with lemon was not refused. Nonetheless, the wine-per-glass is relatively expensive at an average of R100. That’s not steep in fine dining terms, but it looks it when the winter lunch special offers five exceptional plates for R195.

Upper Bloem Restaurant: 65 Main Road, Green Point; (021) 433-1442; reservations@ubrestaurant.co.za: www.ubrestaurant.co.za

The Tesselaarsdal brand was founded in 2015 by long-standing Hamilton Russell Vineyards employee Berene Sauls, the wine made by colleague Emul Ross. The nose of the 2017 shows wild strawberry, red and black cherry plus beetroot while the palate displays plenty of juicy fruit, bright acidity and soft tannins, the finish gently savoury. Already remarkably accessible. Wine Cellar price: R500 a bottle.

Editor’s rating: 90/100.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.

Find our South African wine ratings database here.