Editorial: Beyond the allocation list – rethinking scarcity marketing

By Christian Eedes, 12 August 2025

20

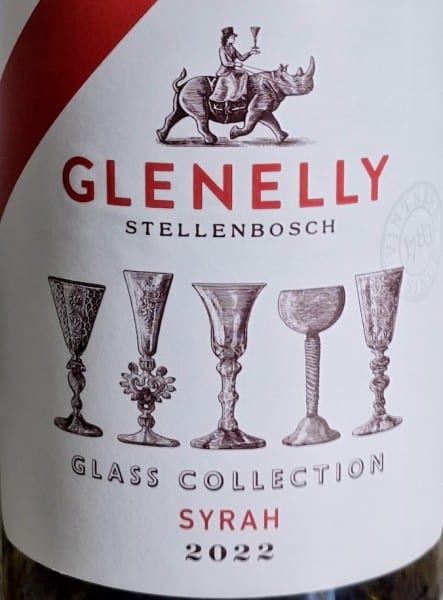

Lately, I’ve been taking great pleasure in the Glass Collection Syrah 2022 from Glenelly in Stellenbosch – Top 10 in this year’s Shiraz Report sponsored by Prescient with a rating of 94 points, selling for R175 a bottle, with a total production of 74 900 bottles. For all its inherent quality, however, its very ubiquity probably counts against it in terms of desirability.

Lately, I’ve been taking great pleasure in the Glass Collection Syrah 2022 from Glenelly in Stellenbosch – Top 10 in this year’s Shiraz Report sponsored by Prescient with a rating of 94 points, selling for R175 a bottle, with a total production of 74 900 bottles. For all its inherent quality, however, its very ubiquity probably counts against it in terms of desirability.

The thing is, scarcity sells. Or at least, that’s the assumption. From limited-edition sneakers to micro-batch whiskies, restricting supply has long been the marketer’s blunt instrument for creating demand. In wine, the allocation list is the purest expression of this tactic: a curated database of “those in the know” who are granted the privilege of buying. The implication is clear – you’re not just purchasing a bottle, you’re securing membership to a select club.

But as anyone who has tried to get onto a high-demand list knows, exclusivity can quickly sour into exclusion. The moment the allocation email lands in your inbox, you are already being reminded that you are lucky to be allowed to buy. And for many consumers – particularly younger ones, who bristle at overt gatekeeping – that’s a problem.

It’s worth noting that scarcity in wine can be entirely legitimate. The top vineyards in Burgundy really are small, and you can’t conjure extra Grand Cru fruit out of thin air. Likewise, a boutique South African producer farming two hectares of old vines simply cannot supply the world. When genuine supply constraints meet sustained demand, a form of rationing is inevitable. That’s fine. What’s less defensible is when scarcity is manufactured – when the vineyard capacity is there, but a deliberate decision is made to withhold, fragment, or throttle stock supply purely to maintain an aura of unattainability.

Artificial scarcity is seductive for producers because it allows them to do three things at once: maintain high prices, signal prestige, and reduce the pressure to actively market. After all, if people are scrambling to get on your list, why bother with trade tastings, media outreach, or building retail relationships?

Yet the hidden cost of this approach is trust. For established customers, the system works – until it doesn’t. Drop off the list through spending fatigue or some other quirk, and good luck getting back on. For new customers, the message is worse: You’re not welcome unless you play our game.

The irony is that scarcity marketing can be most alienating to the very audience the wine industry says it wants to court – Millennials and Gen Z. These are consumers for whom access and transparency are baseline expectations, not perks. They are used to finding information instantly, comparing prices globally, and engaging directly with brands on social media. Will they really wait five years to be deemed worthy of a mixed case? Or engage in an allocation process that feels more like an initiation rite than the beginning of a beautiful friendship?

More importantly, artificial scarcity risks turning wine into a performance of privilege rather than a shared cultural good. The great wines of the world may be rare, but they are not inherently exclusionary – the joy of opening a remarkable bottle should lie in the generosity of the act, not in the fact that you were able to procure it while others couldn’t. The habit of certain collectors going to great lengths to snap up extra stock through retail channels – beyond what the producer originally allocated – is particularly distasteful.

All that said, the onus is not only on producers to make the wine market as vibrant as possible. Enthusiasts, too, need to broaden their horizons. If we are forever fixated on the “rare” – chasing only the big names, the cult releases, the once-a-year allocations – we enable the very system we claim to dislike. There is a vast universe of wines that are beautifully made, fairly priced, and available without the ritualised begging. Drink more widely. Explore unfamiliar producers. Reward risk-taking. The healthiest wine culture is one where curiosity and generosity flow in both directions.

There will always be wines that are difficult to get. There will always be producers whose mailing lists are oversubscribed. The key is not to let the mechanics of scarcity define the identity of the brand. Because in the long run, the surest way to kill desire is to make it feel like a closed shop. And in a world where younger drinkers are already sceptical of the wine trade’s more antiquated rituals, we can ill afford to turn them away at the door.

Real prestige in wine should come from excellence in the glass, not from the artifice of absence – and from consumers who seek excellence wherever it may be found, not only where it is most elusive.

Kwispedoor | 12 August 2025

I’m so over the scramble for rare wines at high prices. Instead of begging for a few bottles or the pressure to buy or some other form of anxiety – all for, let’s say, a R700 bottle – I’ll rather just buy another three excellent bottles of wine without any drama. Ego and sheep-factor behaviour can rob you of a healthy perspective in the blink of an eye. Luckily, here in South Africa, you can drink exceedingly well at very reasonable prices if you taste around enough.

But just clarify this, please Christian: “The habit of certain collectors going to great lengths to snap up extra stock through retail channels – beyond what the producer originally allocated – is particularly distasteful.” Are you saying that, if Johnny loves Wine A and only gets two bottles of it on allocation, it’ll be in bad taste if he buys another few bottles (to drink) via a retailer?

Christian Eedes | 12 August 2025

Hi Kwispedoor, Thanks for your question. My comment was aimed at those who buy vastly beyond their allocation not to enjoy the wine, but to corner the market – either to resell at a profit or to claim bragging rights as to having the largest stash.

If Johnny genuinely loves Wine A and manages to find a few more bottles at retail to drink and share, that’s perfectly fine. The “distaste” is in treating wine as a trophy or a speculative asset, rather than something to open and enjoy.

Jos | 12 August 2025

Hi Christian, speaking of wines that often get treated as a trophy or a speculative asset, have you tasted the new Sadie wines for review?

Christian Eedes | 12 August 2025

Hi Jos, Unfortunately, the current releases from Sadie Family Wines have not been made available for review. Should that change, we would be pleased to taste them and share our notes and ratings.

Jos | 12 August 2025

Thanks for the info, has there been a shift in their policy towards reviewers? If my memory serves me, you usually have the review out at this point.

Christian Eedes | 13 August 2025

Correct — in past years our reviews would be out by now. This year the wines have been released and tasted elsewhere, but not made available to us. I’d prefer not to engage further on this.

Jos | 13 August 2025

Thanks, noted.

Gareth | 13 August 2025

The timing and content of this article (it seems fairly squarely aimed at Sadie et al), as well as your comments on the matter seem to indicate something amiss between SFW and Winemag – and that’s a real shame. Tim’s notes in combination with your scores are a yearly yardstick for those of us who buy these wines every year.

Dion Martin | 13 August 2025

Were you not invited to the trade tasting/open day? If so that is rather short sighted.

GillesP | 12 August 2025

Why should someone be ashamed of buying wines to both drinking it and possibly make returns on extra volume? Wine or rather fine wines is an investment asset too all over the world similar as an investment portfolio of shares or real estate. Think you need a wake up call here.

francois.vanzyl | 13 August 2025

I’m not convinced that South African wine can be considered an “investment asset”. We simply don’t have the volumes or active secondary market for someone to actually include wine as meaningful portion of their total investment portfolio.

I’ll give you an example: Wine Cellar promote their own “wine investment asset” called the PIP and it costs R100,000. They project attractive future returns based on prices achieved at Strauss auctions and via their own brokerage platform. So yes those prices can be achieved, but the volume of wines sold at those prices amount to a couple of cases at best. It is a small number of punters selling a handful of bottle making a few hundred rand per bottle – hardly an investment return.

The free storage period for the 2017 PIP has recently ended and now many of enthusiasts that purchased this “investment” are trying to sell their “assets”. Take a look on the Brokerage platform how many bottles of 2017 wine are available? Hundreds. It will take a long time to liquidate one entire portfolio, if ever. Plus Wine Cellar is taking a 15% commission for selling the wine further eroding the return on investment, if there is a return. Rather drink the wine than try to sell it.

All the empirical evidence I see is that in terms of South African fine wine there are a few enthusiastic hobbyists that occasionally sell some excess wine and make a few rands per bottle, but it is small change relative to their actual investments. They’re not selling wine to put food on the table.

So back to Christian’s statement about the distaste of chasing after limited wine for speculative reasons – I cannot see how someone doing it can actually be making money out of it, so they must be doing it for other reasons which is I would agree is unfortunate.

GillesP | 13 August 2025

Hello Francois. Please refer to the comment I posted on Tim James article on Strauss Wine Auctions Monday. I can assure you that some people can make some decent returns on Sadie wines if bought at allocation pricing and kept for at least 5 years. The same can be said for Porseleinberg, Kanonkop Paul Sauer and perhaps a few additions. I am not talking millions of rand here but if you have several cases of these wines being sold each year, it can be a nice enveloppe.

Jos | 13 August 2025

Sure they can, but you can only buy so many cases from Sadie. His point stands in that you cannot scale that to be an actual investment strategy. Your annual bounty from selling Sadie will be in the thousands, hardly retirement money.

The rest of the wines do not appreciate sufficiently to outperform the stock market on a consistent basis.

GillesP | 13 August 2025

Agreed on that , but back to my original point, wine can be % of an asset portfolio and (especially of you have access to top end Burgundy names and Bordeaux among others) and I surely read here and there that given market returns on Live X it’s not an underperformed asset on long term if with the right ones.

Wessel Strydom | 14 August 2025

Kwispedoor, your comment about Mullineux Kloofstreet is spot on and support the fact that there is many beautiful wines out there at reasonable prices. Could Winemag not perhaps create a platform where subscribers could mention wines that they thoroughly enjoy and punch way above their weight class in terms of quality versus price?

David | 12 August 2025

“Enthusiasts, too, need to broaden their horizons.”

As do critics x

Nicolas Bureau | 12 August 2025

Thank you, Christian, for your enthusiastic feedback on the Glass Collection Syrah 2022.

We firmly believe that delivering high-quality wines at accessible price points is essential in today’s challenging market conditions.

If we’re able to produce this quality at relatively higher volumes, all the better—though of course, 6,000 cases is still modest in the grand scheme of things.

I think we can all agree that making a few barrels of premium wine and selling them at a high price is relatively easy.

The real challenge lies in achieving quality at scale, but also to make it accessible price wise..

Donald Griffiths | 13 August 2025

Sadie Family wines are available on getwine.co.za. If that’s not an allocation myth buster I don’t know what is?

Timothy Conn | 13 August 2025

Thanks for the tip!

Wessel Strydom | 14 August 2025

Sold out at Getwine