Jamie Goode: Do we always want balanced wines?

By Jamie Goode, 2 May 2025

3

Balance is supposed to be one of the four key elements in assessing the quality of wine. The acronym BLIC is often cited as the way to assess a wine’s merit, standing for balance, length, intensity and complexity. This sounds fine, but in practice it’s quite ludicrous. Following this system, I’ve seen some people even go to the bizarre length of timing the length of a wine in seconds. This is wrong on so many levels, and, in truth, the reductionist BLIC concept will do very little to help you assess wines.

The reality is that wine quality is an emergent property of a wine, and can’t be defined or reached by breaking a wine into its component properties. After a couple of decades of tasting wine thoughtfully and at a high level, and having learned from many of the best, all I can tell you is that I know a great wine when I taste it, but it’s very hard for me to explain why. This principle doesn’t just apply to wine. Last night I experienced a thrilling sunset on a perfect evening as I was walking by the river in Greenwich, but I can’t really explain what was special about this one. And what makes a great painting special? Not so easy to define.

The concept of balance sounds really good. And, of course, we don’t want an unbalanced wine. But do we want all our wines to be perfectly balanced? A lot depends upon your definition of balance. Is balance the same as harmony? I like harmonious wines and a lot of the wines I prefer could be legitimately described as balanced, but I think there’s a place for wines that are unbalanced and I’d hate to see these looked down on when they are legitimate styles.

I’m not just thinking of extreme wines, but also wines that are very different in style to the norm. Think the palhete style of red wine. This is a Portuguese term for wines that are made by fermenting red and white grapes together. The result is a pale red wine – one that sometimes could be mistaken for a rosé. It’s an extreme style of red wine, but in the right context, and done well, it’s certainly a legitimate style and this sort of wine can be fine. But, you say, you can have balanced and unbalanced palhetes. I see this distinction, but I think for many, these wines would be dismissed because as red wines, they don’t have enough colour.

OK, sticking with Portugal, what about Vinhão? This is a grape variety, also known as Sousão, but in Vinho Verde it’s called Vinhão and these are inky dark young red wines with very high acidity and some greenness, and they don’t do malolactic fermentation, and they are lovely, especially served the traditional way out of white ceramic cups. These are certainly not balanced wines in any sense of the word, but they are fantastic when done well. As a co-chair at the International Wine Challenge I had a flight of these returned to me all rejected, because the panel (including some very well educated wine people) didn’t know what they were dealing with. Many went on to get strong medals.

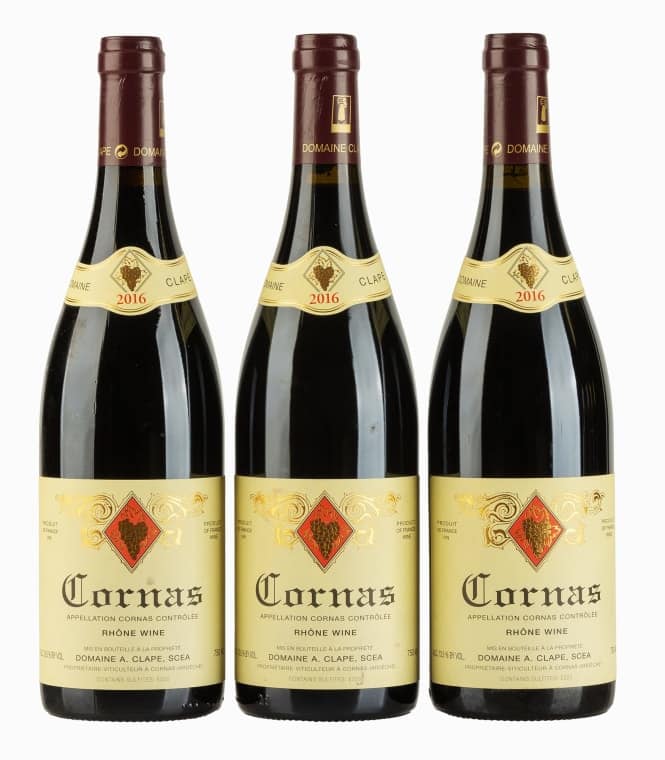

Then we have Riesling. I’ve had amazing dry Rieslings at pH 2.8 that are certainly not balanced, but which are lovely wines. I’ve enjoyed dense, tannic, bold reds from the southwest of France that would have lost their soul and character if they had been tamed. And think of the traditional Syrahs from the northern Rhône in all their pepper, cured meat and olive glory: get a Bordeaux winemaker in with some new oak and tame these, and suddenly while they are polished impressive wines, they have lost what made them truly interesting in the first place.

Think of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc. These grape varieties naturally have some green in their character. Many winemakers, scared of green, try to ripen this out, and in the process they often end up making wines with impressive ripe, dark fruit, but lacking in real personality or interest.

This is the problem with the concept of balance. It can lead to a certain stylistic homogeneity; to boring wines that tick all the boxes, but which fail to thrill. Alongside this concept of balance, we have the problematic notion that we always want to drink the same sort of wine. There are even people who peddle protocols for matching consumers with the right wine for them. The truth is that we want to drink different wines on different occasions. I have lots of wines at home, but it’s not easy finding the right wine for the right moment, even though I have only wines that I like to hand.

I think the concept of balance in wine is next to useless. It should be about whether or not a wine has personality, and whether or not that wine, with its personality, is the right wine for this particular drinking occasion. I want my wines to be interesting, I don’t want them to be perfect. I want them to be authentic. I want them to be true. I can’t stand ‘balanced’ techno wines, even if I can appreciate that there’s a place for them on the market.

- Jamie Goode is a London-based wine writer, lecturer, wine judge and book author. With a PhD in plant biology, he worked as a science editor, before starting wineanorak.com, one of the world’s most popular wine websites.

Alexey Pilin | 3 May 2025

Hello! I think the most important point here is the one in the beginning – it all depends on the definition of “balance”.

But apart from that, with all due respect, I don’t really follow the connection between the examples in the text and the balance in wines. Pale color is not part of balance (for me, and also, for example, for WSET, who also follow the BLIC structure). Peppery Syrahs – can be well bealanced, can be unbalanced. Balance has in my eyes nothing to do with flavors or aromas. Bold tannic reds can also be balanced (by approprtiate flavors concentration, for example and by appropriate acidity level…). And so on.

For me, two things are mixed together here – the concept of balance and the fact, that some wines are made in a style that is too polished, too much “everybody’s darling”, without a kick, without an edge. But for me these are two different things.

Cheers!

Paul Stead | 10 May 2025

I have said this before but I will say it again; put 6 people round a table and pour them a glass of wine from the same bottle.

Each and every one will be drinking a ‘different’ wine.

Why; different palate’s, likes and dislikes and concepts of what is a good wine. You can only give an all round opinion of what is a ‘good’ wine.

Cheers.

Geoff Weaver | 5 June 2025

For me the definition of a balanced wine is one in that nothing screams out to you as a singular character. It could be tannin, acid, sugar or alcohol.

Wines of character and distinctiveness ofter have high levels of say alcohol or acid but if the rest of the flavours are sufficient it will not come across as hot or excessively sharp. So much depends on the concentration of the flavour.

I think it is still an important concept and I am all for wines of real character and distinctiveness.