Jamie Goode: Wine frauds and counterfeits

By Jamie Goode, 8 November 2022

Honesty matters. As consumers, when we buy something, we want it to be genuine. It matters that what we have purchased is the real thing, and there’s trust involved in the act of buying. Especially with wine.

Because there are so many tens of thousands of wines on the market, and every year there’s a fresh vintage, even professionals are trying wines for the first time on many occasions. But as with any other consumer segment, sometimes there are dishonest operators.

There are two sides to counterfeit wine, and they occur at opposite ends of the market. First, fine wine. On the one hand, the perfect conditions for emergence of fake fancy wines have occurred over the last couple of decades. The value of the world’s most famous bottles has soared over my drinking career as they’ve become more sought after globally. Back in the day, a middle-class professional might consider buying the occasional case of classed growth claret, and even one of the first growths wouldn’t be out of reach on a special occasion. And even I remember buying a case of Jamet’s Côte Rotie 1999 en primeur. But now the top wines are insanely expensive. A case of Grand Cru red Burgundy from a top producer is now the price of a good second-hand car. The fact that fine wine now costs serious money has made fakery potentially lucrative. If you are buying anything with some bottle age, be very careful indeed.

Then we have fake commodity wine. There’s little money to be made faking modestly price wines, but when we get to the bottom of the market, there’s another sort of cheating that occurs. This is when bulk-shipped, bargain-priced wine is re-badged as something that the market is willing to pay a little more for. The French take this sort of fraud very seriously, and people go to prison if it is found out. In other countries, it seems to be investigated less vigorously. But there’s a clear incentive to cheat if customers might not spot the difference. Another form of cheating happens when a buyer tastes a sample, and then the producer sends another wine – in this case the bait and switch may not involve illegal labelling, but simply commercial dishonesty.

The first time the wine world really took note of fine wine fraud was when Hardy Rodenstock managed to procure the now infamous Jefferson wines. A music publisher with a knack for sourcing rares, Rodenstock discovered 18th-century bottles of Bordeaux in a walled-up Paris basement in 1985. The now-deceased Rodenstock managed to deceive quite a few notable wine folk with his fakes, and the story is told very well by Benjamin Wallace in his book The Billionaire’s Vinegar. Publication in the UK was later blocked when Wallace and his publisher were sued for libel by a well-known auctioneer who had sold the Jefferson bottles, but the book is still available internationally.

More recently, the spotlight has been shone very brightly on the issue of wine fraud by the publicity surrounding Rudi Kurniawan, who for a good while was right at the heart of the New York fine wine scene. Known on the internet bulletin boards as Dr Conti, he infiltrated the high-roller wine collector scene, and in turn deceived a lot of people with his fakes.

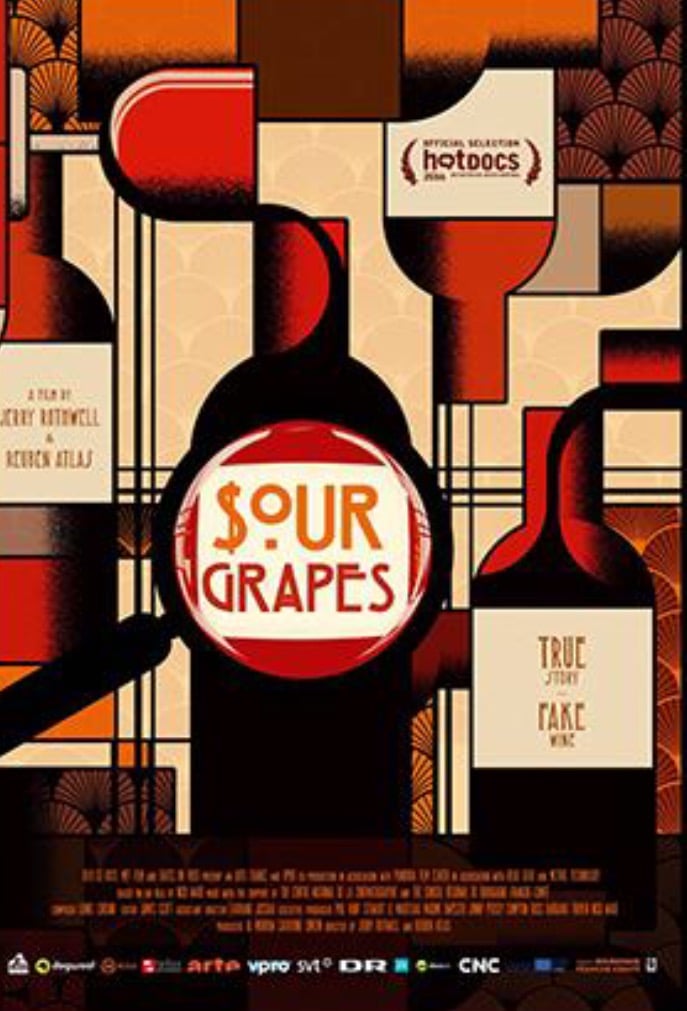

The 2016 film Sour Grapes has told this story well. Kurniawan seeded the market with genuine wines, built up credibility, and then started feeding his specially concocted fakes into the auction scene. Famously, Laurent Ponsot stopped an auction that included fake Ponsot wines. How did he know they were fakes? These wines had never been made by Ponsot! Kurniawan ended up going to prison after a trial in 2013, but has now been released and there are some reports that he’s planning to rejoin the wine industry in some capacity.

Why is fine wine fakery such an issue? There are several reasons. First of all, it’s potentially lucrative because these wines are worth so much. Secondly, who really knows what a lot of these wines taste like? Very few are drinking the old vintages regularly, and even if they are, there is so much variation because of cork performance over many decades, plus variation in storage conditions that the chances of a fake wine being spotted by drinkers is quite slim, if the fakery is done with some skill. And then auction houses have an incentive not to do too much due diligence on wines offered to them. Even if they are skilled, how can they be sure that a particular lot is counterfeit? Especially with older wines that have changed hands a few times, it’s such a difficult job. Some auction houses are better than others: a few recent sale catalogues have been pored over by experienced, knowledgeable collectors who have outed suspicious wines in the sale that the auction house either hadn’t picked up, or deliberately didn’t question too closely.

One practice that has opened up the door to fakers is that of re-corking. Corks don’t last for ever and some châteaux have, in the past, offered a re-corking service. With good record-keeping and good technical proficiency, this is a useful practice, especially because it ends up removing some out of condition wines from the market. Penfolds, for example, taste the wines they re-cork and if they aren’t up to scratch they just get a generic cork and no certificate, and are effectively worthless on the secondary market. But where recorking is done without record-keeping, it’s a green light for fakers who simply need an old bottle to refill and recork.

Maureen Downey is a leading expert on fine wine fraud, and her company Chai Consulting works with collectors to help verify bottles. She has a horse in the race, of course, but thinks that there is a lot of fraud going on at this end of the market, and has publicly outed people who she thinks are complicit in this activity, or who aren’t doing their job properly stopping these wines being traded.

Now, there is a concerted effort on the part of producers to counter the potential for fraud on current releases, but these steps can’t be retroactively applied.

What about at the bottom end of the market? It’s impossible to say how much of an issue fraud is here. It’s hidden. Occasionally it comes to light, but there’s no way of knowing how much illegal activity is taking place. There are lots of estimates cited, but these are just guesses, and whenever anyone tries to verify them by going back to the source studies, it turns out someone has made a guess and then repeated citation of this guess has somehow turned it into a data point. Clearly some commercial operators who are fighting fraud at the top end want everyone to be scared by the extent of fraud, even though there’s very little in common with what goes on at either end of the market.

Back to the theme of honesty. There are other ways that wine producers can be dishonest without being illegal. This could be competition special wines, or particular barrels for en primeur tastings that aren’t representative of what will be bottled, or even the Canadian situation where some of their famous producers perfectly legally produce international-Canadian blends (ICBs, or IDBs for international-domestic blends, also known previously as cellard-in-Canada wines) – here the issue is that these brands are closely associated with Canada, but have just a little Canadian wine in them, with the rest bulk wine from other countries. And in Champagne there’s the much discussed sur lattes auctions, where Champagne houses can buy Champagnes made by others still en tirage and then disgorge them and put their label on the bottle.

But the real challenge is the one facing fine wine, and in particular those who have the resources to buy very old, famous wines. Provenance isn’t always easy to prove, and when fake wines have been bought and kept in a collector’s cellar for a few years, they undergo a sort of santiization process where their partial provenance means that people trust them rather more than they should

- Jamie Goode is a London-based wine writer, lecturer, wine judge and book author. With a PhD in plant biology, he worked as a science editor, before starting wineanorak.com, one of the world’s most popular wine websites.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.