Michael Fridjhon: Swartland’s visionaries reunite to celebrate a movement that changed SA wine

By Michael Fridjhon, 15 April 2025

4

There’s no doubt that wine regions define their own personalities – driven by the landscape and the people who are attracted to making wine there. The Medoc was shaped by the aristocracy of Bordeaux who built their grand chateaux and planted vines as part of their self-defining vision. When it turned out that the wines were rather good (and appealed to the English market which could be serviced from the port of Bordeaux) the scene had already been set.

Burgundy, on the other hand, was shaped by the French Revolution and its aftermath: the expropriation of the church properties put the great domaines into private hands while the Napoleonic laws of inheritance compelled the new owners to divide the estates equally amongst all their heirs. Two hundred years after the fall of the ancien regime, the once-large properties have been fragmented into tiny parcels owned by the many descendants of many generations.

The wines of Bordeaux express the great estates which dot its landscape. The wines of Burgundy trade in tiny volumes, their message the significance of fractional sites and the nuances of terroir.

In South Africa it’s not difficult to see Stellenbosch as our version of the Medoc. The properties are generally quite big because they weren’t divided up. The younger sons established their own farms after moving off the land when the oldest son inherited. The proprietors who remained lived their lives as the citizens of a settled community within easy distance of the capital and the harbour through which much of their agricultural production left the colony.

The democratic transition of 1994 created a unique opportunity for adventurous young winemakers supercharged with enthusiasm and impecunious enough to have very little to lose. Their new frontier was less about an undiscovered land and more about a mindset, a different and less derivative way of doing things. They saw themselves as pioneers because they were imbued with a pioneering spirit. This was an identity which coincided with the age – South Africa was setting out on a largely uncharted course.

They chose the Swartland and its hard, dry, unforgiving landscape in part because it expressed this vision, in part because it was just distant enough from the mainstream to escape the gravitational field of the old Cape wine industry. Most important however was the collection of old vineyards planted to unfashionable varieties. The farmers who owned them had been selling their grapes to cooperative cellars for whatever they were paid (generally not enough to cover the farming costs). The new arrivals had a better sense of the value of the fruit, and were ready to invest accordingly.

A quarter of a century later it seems as if it their conception of the Swartland had always been there. Despite the fact that several of the key protagonists are little more than fifty years old, the wines have been vinous benchmarks for at least two generations of consumers.

A key component of what created this aura around the place and the people whose wines are identified with it was an event launched in 2010 as The Swartland Revolution – a brand charged from the outset with connotations of resistance to the vinous establishment. It was a party for another era, a weekend where the formal tastings sometimes seemed a little like essential window dressing to justify the inevitable night of music and carousing. It ran its natural course, and by 2015 the Revolutionaries decided to call it a day.

But nostalgia is a strange thing: it makes men with fully developed frontal cortexes believe that they can fly from rooftops. So ten years after the last ever Swartland Revolution disturbed the peace and calm of Riebeek-Kasteel, they were all back, ready for one more blow-out.

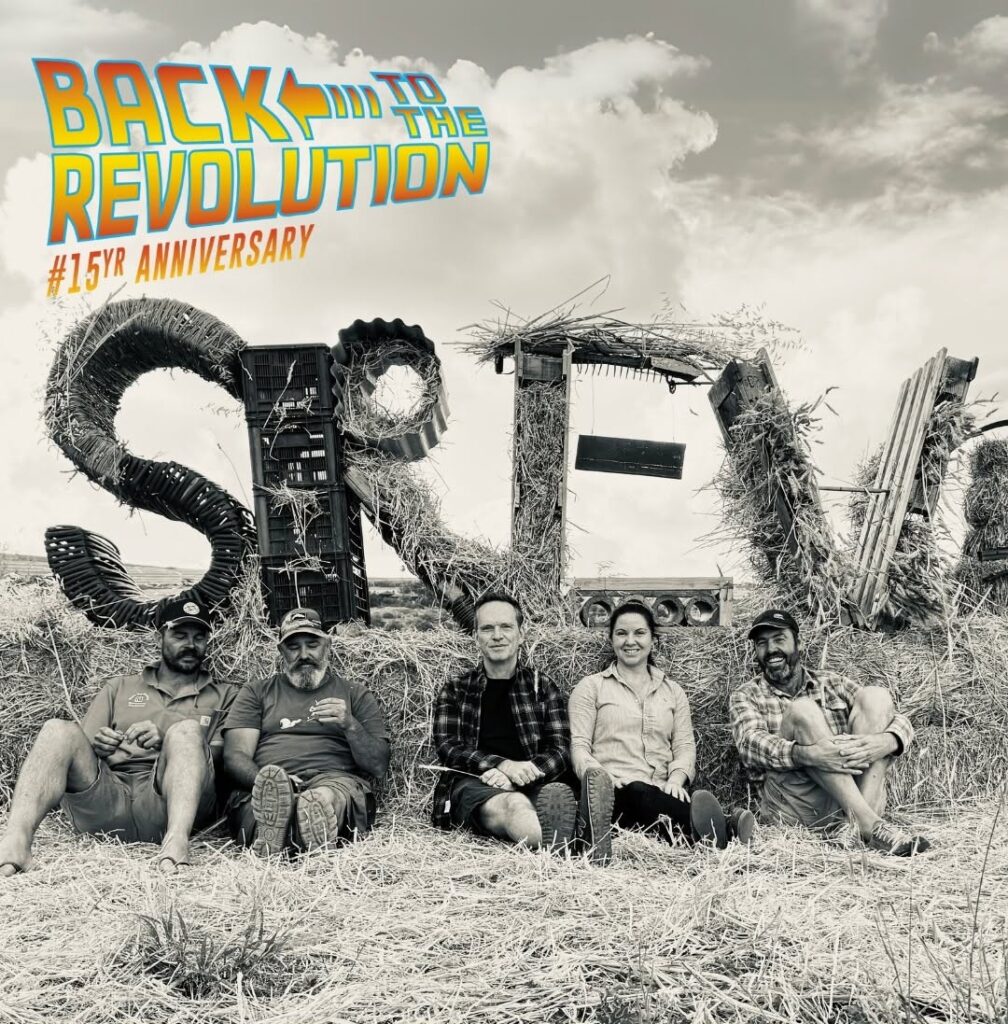

The Swartland Revolution of 2025 turned out to be bigger and better than any I attended in the days when the unrealities of the founders’ achievements infused the events with the craziness that only survivors of a plane crash can begin to understand. This was partly a function of the venue. Unlike the previous iterations which depended on urban facilities, this was set on open land in the shadow of the Paardeberg. Everything was brought to the site and contained within walls of hay bales. It was as if everyone – from the Revolutionaries themselves to their guests who had come from almost every continent – discovered as they entered the Stonehenge of hay that they had been disconnected from reality.

But there is very little that is crazy about Eben Sadie, Adi Badenhorst, the Mullineuxs and Marc Kent. The Swartland – what it is and what it means for the Cape wine industry – is their conception and their creation. They aren’t likely to jeopardise it for one last party under a starry sky. There was a real reason to host this (perhaps final) bash. From 2010 to 2015 the Revolution was an act of bravado, an affirmation that their quest for a new vinous Golconda was very much alive – even if its sustainability seemed questionable. This is no longer the case: they have passed through the fire and it has burnished them with the armour of certainty.

They know why and how they are different from the rest of the industry. Stellenbosch makes so many different (and generally quite classical) wines so well that it is constantly comparing itself to Bordeaux (cabernet and red and white blends) and Burgundy (chardonnay). Elgin and Hemel-en-Aarde battle it out over their cool climate assertions with the shadow of the Côte d’Or looming over them. Constantia’s sauvignon blanc claims wrestle with the noise of the Loire and New Zealand’s South Island.

The Swartland is about itself. Its founding protagonists knew what they wanted it to be before they had the words to express it or the means to achieve it. This year, at the Revolution, it was there for everyone to see. For all the noise and music, and the apparent madness of the moment, it wasn’t chaos. Like the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics, it wasn’t like anything which had come before. Just as no other city and no other nation could have pulled off that occasion – rain and all – only the Swartland could host this Revolution.

- Michael Fridjhon has over thirty-five years’ experience in the liquor industry. He is the founder of Winewizard.co.za and holds various positions including Visiting Professor of Wine Business at the University of Cape Town; founder and director of WineX – the largest consumer wine show in the Southern Hemisphere and chairman of The Trophy Wine Show.

Howard Kelly | 16 April 2025

Fantastic article Michael – you’ve hit the nail on the head!!! It was a wonderful event and did justice to the exceptional wines and exceptional people who make them. Thank you to the Mullineuxs. Kallie Louw, Adi Bardenhorst and Eben Sadie for putting on an incredible event – no reason not to be looking forward to Swartland Revolution 2026!!!!

Greg de Bruyn | 18 April 2025

Yes, but you’ve said nothing about the event. What about the revelations of the Uco Valley with their lodestar Zuccardi, the intensely entertaining play of the core members, the embarrassing roasting of poor Peter Fraser? I get the impression you wrote this before you went.

Michael Fridjhon | 22 April 2025

Hi Greg

I don’t think WineMag’s editor would object to your writing the article you would have preferred to read – so why don’t you submit your own take on this year’s event, replete with whatever impressions you feel like conjuring up?

YEGAS Naidoo | 24 April 2025

Greg de Bruyn somehow I do not think the original décor aesthetics would have been shared with MF beforehand. The ” Stonehenge of hay bales ” emerged from the rocky terrain with as much surprise as the borewors chandeliers and curtains of potatoes that featured as part of the festival feed for the 300+ guests. Certainly sights to behold for the uninitiated.