On old wine

By Christian Eedes, 31 March 2022

6

The last time I tasted Chateau Libertas 1940 was on the occasion of the brand’s 80th anniversary in 2012 when the information to hand suggested that its constituent parts were “predominantly Cabernet Sauvignon but including Cinsault and some of the Port varieties” while the alcohol was given as 14.93%. My tasting note at the time was as follows: “Decaying forest floor, orange rind and caramel on the nose. Rich, thick textured and mellow on the palate. Not unlike Tawny Port.”

Earlier this week, I got to revisit the wine as part of a recorking process in the lead-up to the “Distell Tabernacle Heritage Sale” (working title) to be held later in the year. The Tabernacle is producer-wholesaler Distell’s famed 12 000-bottle wine library dating back to 1979, and custodian Michael van Deventer has selected some 35 different items for auction by Strauss & Co. All those put forward were inspected for soundness, after which they were fitted with new corks, and I got to taste through the line-up, tasked as I was with writing notes for the catalogue.

The 1940 vintage of Chateau Lib is something you can’t help but treat with veneration, but it doesn’t necessarily give you goosebumps or send shivers down your spine. The remarkable thing about it, however, is that it seems to have arrived at a point in its development where it seems just about impervious to the passage of time – my experience of it now seemed remarkably like how it presented 10 years ago, my updated tasting note as follows: “Caramel, some nuttiness, meat stock and the last vestiges of red berries on the nose. A hearty wine, still showing surprisingly good volume and freshness on the palate although the tannins have long since mellowed. Holding very well and fascinating to drink”. Rating: 92/100.

The line-up containing everything from relatively humble Stellenbosch Famers’ Winery Cinsaut 1974 to the revered GS Cabernet 1968 showed remarkably well with very few outright duds although a few caveats must be added. As mentioned, every bottle in each individual parcel of wine was checked for freedom from fault (a minute sample taken via pipette and later topped) and by my estimation, the rejection rate was around 5%. Bottle variation is a huge factor on wines of significant age, but this is something that most wine lovers are at least resigned to.

Secondly, knowing in advance that you are tasting wines carrying meaningful time in bottle, you inevitably adjust your expectations, becoming more tolerant of mature characteristics. Tasting a wine 10 years from vintage, the issue is often about whether a wine is looking prematurely developed whereas tasting a wine after 40, 50 or 60 years, development is a given and what’s at stake is more about how pleasing that development has been.

This brings me to another, perhaps more philosophical, insight. Drinking an aged wine is essentially about investigating to what extent whatever’s in your glass is managing to avoid decrepitude and, ultimately, death. Presuming some sort of pedigree, a wine is going to survive for a certain amount of time, but the great wines are those that don’t just survive but become more pleasurable and more interesting to drink. Or, if you will, great wines are those that don’t just live a long life but do so with panache.

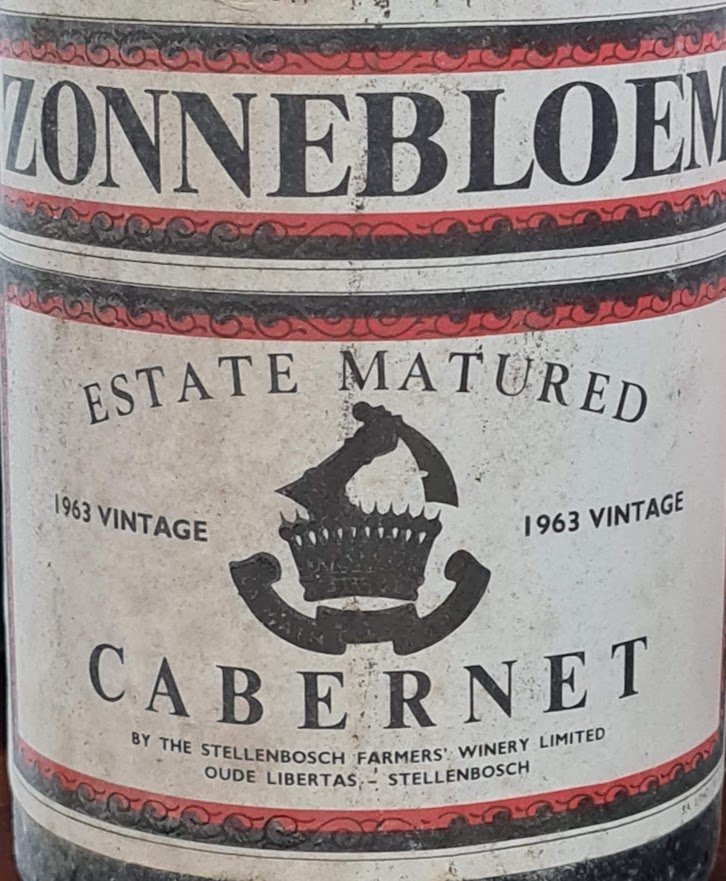

Apply this criterion, then, the top wine of the “Heritage Sale” tasting was the Zonnebloem Cabernet 1963. My note as follows: “Enticing and complex aromatics of red and black berries, flowers, dried herbs, earth and spice. The palate has a wonderful sinuous quality to it, which is to say it possesses both weight and poise – dense fruit, bright acidity and tannins that still lend shape. Very much still intact”. Rating: 97/100.

Comments

6 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.

Erwin+Lingenfelder | 31 March 2022

Were there any 1957s?

Christian Eedes | 31 March 2022

Hi Erwin, Indeed there was – the Lanzerac Cabernet 1957. Thought to actually consist of Cab, Shiraz, Hermitage (Cinsault) and Pinotage!

Erwin+Lingenfelder | 31 March 2022

Thanks Christian, I will look out for it!

Higgo Jacobs | 31 March 2022

The 1957 Lanzerac Cabernet is in drinkable condition Erwin, but certainly not one of the standout wines. The wine you want to look out for from the 1957 vintage is the Chateau Libertas ’57. Wasn’t part of this tasting / re-corking though.

James | 31 March 2022

I have a fair few bottles of 70s, 80s nederburgs and a few zonnebloem’s, although i cannot speak of their full provenance. Mainly from various nederburg auctions.

I am afraid they are past their sell by

Pat Naidoo | 4 April 2022

I have Monis Stamp Collectors 1948 Port.

Unfortunately the labels got lost probly thru moving houses. Appreciate any help Christian.