Tim James: Saliva and wine

By Tim James, 19 July 2021

2

If you’re sensible as well as squeamish, you will not have peered too closely into a winetaster’s spittoon. But if you have (huh, Kwispedoor?), you should have realised, from all those unattractive, mucusy strings, that saliva has played a role in what’s going on in there. And, indeed, winelovers should recognise the role that saliva plays in drinking (and eating, of course). Including its significance, as a dwindling product of a taster’s mouth, in wine competitions: overworking saliva with too much tasting and spitting leads to build-up of acid and, especially, tannin in the mouth, fundamentally altering balance and even flavour and thus helping to account for some of the odder results in scoring big line-ups.

Tasters’ saliva flows are all individual too, like many of their flavour threshholds (look at the comparative lists of mentioned aromas and flavours in different tasters’ notes and you can often wonder if they were assessing the same wine – but that’s another story). Apparently, a person secretes from half a litre to three times that – daily.

I’ve been recently reminded about the soldierly but unsung efforts of saliva in promoting oral satisfaction because I’ve been suffering for a few weeks from a (fairly) dry mouth. Something is inhibiting my saliva flow. Perhaps I’m more vulnerable to this than many as I did have one of my salivary glands (we have three major and hundreds of minor ones) surgically removed a few decades back, after repeated blockages. I’m now wondering if a moderately reduced saliva flow has accounted over the years for what seems like an idiosyncratic extra sensitivity to bitterness – I’ve been aware of the sensitivity, so I never publicly describe a wine as bitter without first checking with other tasters. Interestingly, the flow or its effect seems inconstant, so a wine might taste bitter to me one day but less so the next – probably others will have noticed the pattern, which is yet another reason not to bet too much on a single blind tasting.

Anyway, now my saliva flow is definitely reduced and I’m hoping that my newly dry mouth – not an uncommon condition, I believe – will prove to be a temporary condition. It prompted me to do some research, and I’ve been surprised to find out just how much study there has been of saliva and the way it mediates how we experience wine.

According to one article on the World of Fine Wine website, the winelover’s real interest in saliva is that it contains certain proteins that bind with tannins. Mucins in saliva lubricate and protect the surface of the mouth. “Tannins remove this lubrication, causing a sense of dryness, puckering, and loss of lubrication in the mouth. This is what we describe as ‘astringent.’” The problem for tasters faced with a long line-up of wines to be tasted quickly is that this astringency builds up, as saliva can’t keep up the pace with replenishing the lubricating layer. The tannin content of white wine is obviously less than for red, but the acidity is usually higher, and “frequent exposure to a high acid stimulus is likely to overwhelm the buffering and dilution capacity of the saliva. This can leave the mouth feeling sensitive to subsequent samples and might lead to acidity being misjudged”.

The anonymous author of this article says that all this should not lead professional wine-tasters to despair (little chance of that, I would suggest!), although palate fatigue is “near fatal” for assessing elegance and harmony, which “depend in large part on mouthfeel”. But, the author adds, “it is an observation that should encourage us to approach tasting with a degree of humility” (um, perhaps a slighter great chance of that, now and then).

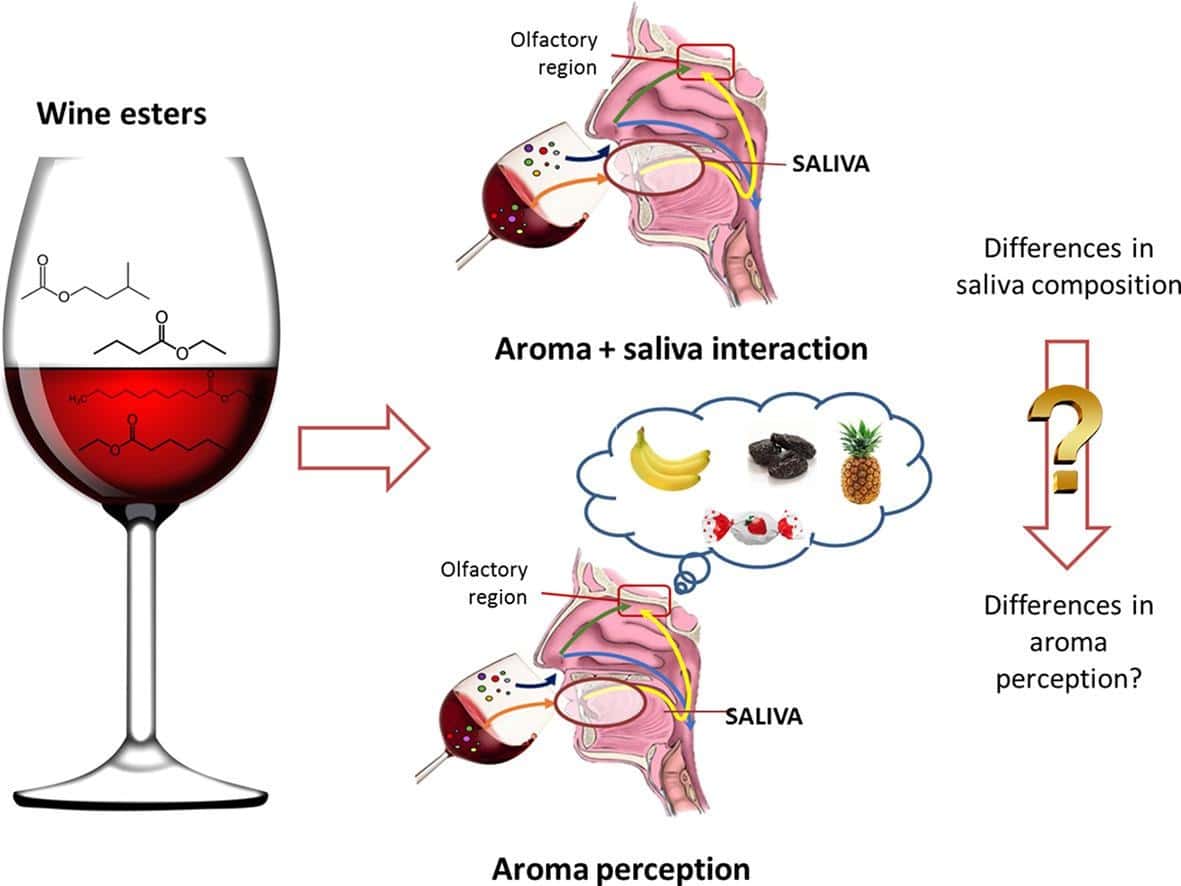

There’s more to the role of saliva than all that, apparently. I did notice, for example, but confess I didn’t approach too closely, a scientific paper in Food Research International entitled: “Effect of saliva composition and flow on inter-individual differences in the temporal perception of retronasal aroma during wine tasting”. And how about, in Food Chemistry: “Simulation of retronasal aroma of white and red wine in a model mouth system. Investigating the influence of saliva on volatile compound concentrations.”

A rather less formidable-looking discussion of the importance of saliva in wine-tasting starts off by pointing out that “We are, in fact, working with personalized sets of molecules from the moment wine hits mouth … there are things going on in your mouth that change the way your wine tastes, and they’re not the same for everyone.” There are enzymes as well as proteins involved, it seems (and saliva can thus even affect aroma). Some of them are devoted to breaking bonds with sugar molecules. The author points out that “if you chew a bite of bread or potato long enough, it will begin to taste sweet as your saliva breaks the starch down into simple sugars”. And further: “On contact, your saliva begins liberating wine aromas into the air inside your mouth and the back of your throat (the pharynx) where they can travel up to your nose (the ‘retropharyngeal’ path) and be smelled.”

Other enzymes and proteins are active, and I found this paragraph interesting: “The quick shift from wine’s strongly acidic pH – usually pH 3-4, somewhere between cola and orange juice – to your saliva’s fairly neutral one also changes the chemical form of some molecules, sometimes changing them from aromatic to un-aromatic versions or vice-versa. All of this explains why a wine’s flavor seems different in the afterglow of swallowing compared with when you take that initial exploratory sniff. It isn’t just the addition of the basic information your tongue can contribute about sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. You’re actually creating new aromas as you sip, swish, and swallow.”

One conclusion is clear about all this: saliva helps explain, as this author says, “why humans are so inconsistent about describing what they put into their mouths”.

As for my personal plight, I’m also suspecting that my current inhibited saliva flow can lead to some intensification of certain flavours as well as textures, especially if I am tasting repeatedly. Which I should be at this time of year, as the next edition of Platter gets assembled. However, unfortunately, the Platter process has been badly affected by the prohibition on moving wine. I must just hope that by the time the flow of Platter samples resumes, the flow of my saliva will also be back to normal.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. He is a taster (and associate editor) for Platter’s. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013

Help us out. If you’d like to show a little love for independent media, we’d greatly appreciate it. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

Comments

2 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.

Stewart Prentice | 20 July 2021

Fascinating article Tim. Is one logical conclusion to have 1 or 2 glasses of your best bottle first and then downgrade appropriately?

As an aside, Sideways may have ruined Merlot’s reputation for a generation of the influenced (are these the people who follow influencers I wonder?), but the spittoon scene is still very funny.

https://youtu.be/PPKdHP8zWuo

Kwispedoor | 19 July 2021

Thanks for a very interesting article, Tim.

I have indeed peered closely into a spittoon or two. But, fair warning: if you gaze long enough into a spittoon, the spittoon will gaze back into you. And if you spit while gazing, the spittoon might even spit back at you!