Tim James: The Swartland Revolution – 15 years of great change

By Tim James, 5 May 2025

1

With the publicity about the latest and almost certainly the very last Swartland Revolution, I was pushed back in my mind to the first, in 2010, and the differences between then and now – apart from the fact that I was there at the first (and all the others till this year). Least importantly, perhaps, but Christian Eedes would be interested to know that attending the inaugural event cost the punters (just 150 of them) R1750, a very sizeable sum (read his thoughts on this year’s event here). Also that journalists were much more sought after by the Revolutionaries back then: Michael Fridjhon was invited (though he wasn’t, I’d say, a True Believer in those days) to open the event and launch the Swartland Independent Producers; I (a devoted Believer) moderated the seminar and tasting given by the hosts; and one Neil Pendock (who knows?) tried in vain to emcee with a magaphone the boisterous post-Revolution “Real Men Ferment Wild” tasting of the wines of 22 Swartland Independent Producers on the Riebeek-Kasteel street. This year, the only journalist with an official function was an important foreign one – Tim Atkin; a shift which in itself doubtless signals quite a few changes of orientation, priorities and ambitions.

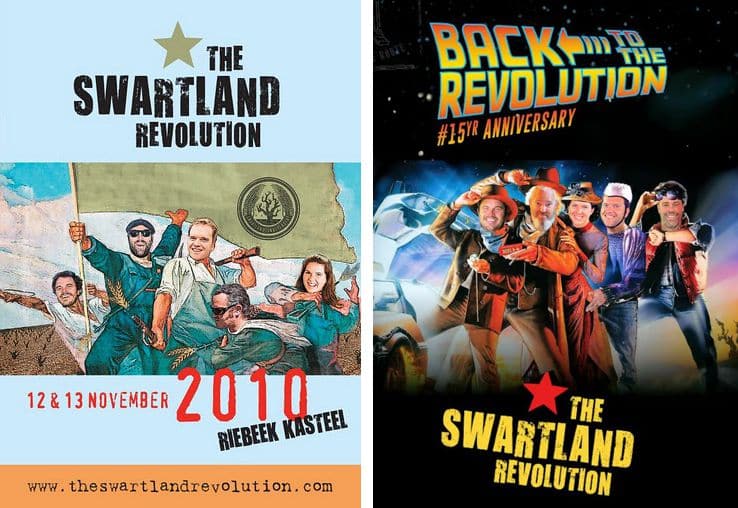

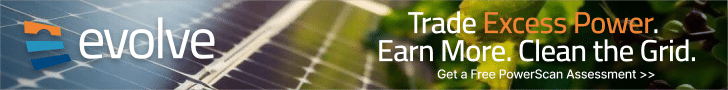

More significantly, not only were the Revolutionaries fifteen years younger back then, but so were their wineries. Just look at the youthful energy depicted on the poster! (Do you know that the ears of wheat hippyishly poking out of the rifles were a late addition following objections to the implied violence of the guns? Personally, I dourly felt even then that invoking the imagery at all was a culpable trivialisation of serious matters.)

Just think of the remarkable advances they’ve made, and how prosperous they’ve become! It’s interesting that the success has followed very different basic patterns of business development for the four producers.

In 2010, Adi Badenhorst was still struggling to rejuvenate the vineyards and the cellar (and homestead) on the Kalmoesfontein farm acquired two years earlier in partnership with his cousin Hein. Basically, he was making a Red and a White, that’s all. Now, at least partly thanks to huge and clever efforts and the great success of the Badenhorst second label, Secateurs, as well as the more prestigious success of the main range, the Badenhorst holdings have organically spread widely across the Paardeberg, with yet other vineyards leased. Adi is quite a big landowner.

Sadie Family Wines has also become a significant landowner on the Paardeberg, though on a lesser scale than Badenhorst. In 2010 Eben and his family were still living in very modest rented accommodation and there were no vineyards or modern winery on the small home farm. But this was the year he did his final harvest in Spain and could further concentrate on Sadie wines – bringing out the maiden vintage of the Ouwingerdreeks (recently renamed Distrikreeks) to complement his two signature wines. Sequillo was another venture, but it wasn’t to survive his business plans. Fifteen years of fast-growing international fame later, the home vineyards (largely experimental) are thriving, and adjacent land and vineyards have been bought. There’s a rather splendid collection of winery buildings as well as a family home. If the Badenhorst achievement involved a partnership to bring in capital, the Sadie growth has been entirely independent (with some no doubt willing help from a bank for the recent building programme).

A third model of growth was followed by Andrea and Chris Mullineux. In 2010, they were simply Mullineux Family Wines, with minimal outside investment. That year, two years after the maden vintage, they’d taken a lease on a small building in Riebeek-Kasteel to establish their own winery, although initially only for maturation (their first vintages of Swartland wine had been vinified in Stellenbosch and then, closer to home, at Meerhof). But 2010 was also the year that mega-rich Analjit Singh visited South Africa for the first time (bringing his son to the soccer World Cup); some years later he formed a major partnership with the Mullineux. Purchase of the Roundstone farm on the Kasteelberg and building a substantial winery there was the next step in their major expansion as Mullineux & Leeu Family Wines (including Leeu Passant in Franschhoek).

Callie Louw of Porseleinberg was the fifth figure on the 2010 Swartland Revolution poster, but his maiden vintage of that year (made in the simplest of cellars, from fire-damaged vineyards) was not poured at the event – I couldn’t remember this, but he confirms it. Callie was the only one of the Revolutionaries not to at least substantially own their own brand, and that remained the case in 2025, though he’s greatly built the reputation of the single Porseleinberg wine, and overseen the major expansion of Porseleinberg as a grape producer for the home cellar of owner Boekenhoutskloof too, as well as of other, newly acquired and developed Swartland vineyards. We can but hope that Callie, too, has become much richer over the years. It’s worth pointing out that Marc Kent, visionary leader of Boekenhoutskloof, was, along with Eben Sadie, perhaps the most ardent Swartland visionary, and a major inspiration behind the Swartland Revolution both in 2010 and its revival in 2025. He’s lurking, modestly invisible, in the posters.

Big changes, then, in 15 years for these four producers, especially for the family-owned ones, from what now seem to have been the comparatively tentative early days of 2010 and the inaugural Revolution. The unifying factor behind the success is undoubtedly the extremely hard work that has gone into it.

To finish on a less positive note. The one truly disappointing change since the 2010 event, which proudly featured the logo of the Swartland Independent Producers on the poster’s flag, and on the programme for the Saturday afternoon, is the effective demise of that splendidly ambitious initiative. For those who’ve forgotten, it was born of a noble aim to emulate the best elements of European appellation rigour: members voluntarily using rules and recommendations to stress the claims of terroir, and improve wine quality and the reputation of the Swartland as a whole.

It’s not the place to analyse the reasons for the collapse of this ambition and of the SIP, largely in favour of individual ambitions and a more lowest-common denominator approach to rather join with the Swartland Wine and Olive Route and its basically marketing role. I’m sure there were pressing pragmatic reasons. Time and place, though, to note, some regret. Is the revolution dead, despite a more-or-less successful final Revolution event? Romantically yes, I’d say; realistically no, far from it. The Revolutionaries are all markedly richer, the fancy foreign journalists are hooked as they actually weren’t back in 2010, and the Swartland produces greater wines than ever, and more at that level, with many other fine producers alongside. Just a few sentimentalists, looking back at the more heroic and visionary days, have some regrets intermingled.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Michael Fridjhon | 7 May 2025

This is a wonderful and thought-provoking review of the Swartland Revolution, from its earliest incarnation to the great re-run/re-make of this year. As always Tim writes with a profound sense of the past while avoiding the puffery of the present.

I see very little to regret about how things have evolved. The guardrails of the now defunct Swartland Independent Producers’ manifesto may have ben dropped but this leaves choice in the hands of consumers, which is where it should reside.

As a matter of record, Tim, you’re right that I wasn’t a true believer in 2010. Nor am I now – it’s wine after all, not religion, and everything about it should be interrogated all the time, with nothing taken on faith.