Tim James: Welgemeend – rise and decline of a fine wine producer

By Tim James, 28 April 2025

10

Sometimes, reflecting comfortably enough that the past is a foreign country, it’s a jolt to realise how damn foreign it was. Do South Africans maybe forget that too easily? Which doesn’t help us to have any true understanding of where we are now. Even leaving aside the larger, important issues, consider our own dear wine industry and the stranglehold that the KWV, with its quasi-statal powers under the apartheid regime, had over it until the 1990s. Consider the quota system it controlled, whereby a wine producer, or would-be producer was allowed to make and sell wine only if there was a quota for the farm producing the grapes. And it seems that if you wanted to make serious wines in, say, the Hemel-en-Aarde, like Tim Hamilton-Russell, it was much more difficult than getting the go-ahead for yet more plonk in the hot and irrigated areas near the big new dams on the Breede, Olifants and Orange.

The quota system was abandoned in the mid 1990s along with most of the other KWV controls (but its largely useful certification practices remained). I wonder how often it occurs to the younger generations that if the overturn of practices like quotas and minimum pricing hadn’t happened, and especially with the consequences for the co-ops of KWV controls and support disappearing, perhaps nor would much of the excitement of 21st-century Cape wine have happened. There’d have been that much less of finding great old vineyards that used to feed the co-ops, buying the grapes and making the wines that now give so much pleasure around the world.

I was thinking of good old, bad old days because the eminent viticulturist Etienne Terblanche asked me about the early days of Welgemeend Estate in Paarl and of Billy Hofmeyr’s vineyard practices. He’s long been interested in the estate, but is now particularly so because of the terroir which, he says, “seems very similar to Vilafonté and Bacco – both of which are challenging but produce quality wines”, as did Welgemeend. Things are very different at Welgemeend since it was sold in 2007; I don’t think any estate wines are made there now; I suspect that few readers of this website under the age of 50 will have even heard of it, let alone realise its significance in modern Cape winemaking (see here for a somewhat sentimental notation from the editor).

Etienne wanted a level of information about Welgemeend’s early years that I didn’t have, as my friendship with the Hofmeyrs dated back only to the early 1990s. By then, Billy, only in his early 60s, was already suffering from Alzheimer’s. His wife Ursula was in charge of the vineyards, and his daughter Louise had largely taken over making the wine – she’d needed to rescue the 1990 vintage from the consequences of Billy’s deteriorating attention. So I turned to Louise, now living in Paarl (Ursula died some years back), and set her on a little trip into that foreign country.

Billy was a great lover of wine, especially Bordeaux, and a fine taster – including on a competitive level. While he continued to work as a land-surveyor for some years, he and Ursula bought the small farm near Klapmuts in 1974 to begin a fuller life in wine. Says Louise: “He had looked aound extensively and worked on a small budget because he didn’t want to be spending too much on a mortgage. Let’s just say that Welgemeend (Montevideo as the farm was then called) suited my father’s needs and they loved the view.”

It was a totally different experience from that of the new wave of winemakers this century. The winemaking context in the Cape was one of estates, merchants and co-operatives. It was still a decade before Neil Ellis became the first local to establish a negociant business, buying in grapes from around the Cape to make serious wines from under his own label.

As Louise says, the new approach “particularly makes sense now because of the time and cost of owning a vineyard and winery. My father did it in record time but it was still five years and a very small young crop.” There were grapes on the farm at the time of purchase (less than five hectares of chenin, hanepoort and cinsaut – all to be replaced soon), so it had the vital quota. Louise has the original bank deposit slip showing the co-op’s 1974 payment of R438.96, with a note from Billy stating (in both English and Afrikaans) that “this deposit slip reflects the total vineyard income for our 1st year on Welgemeend”.

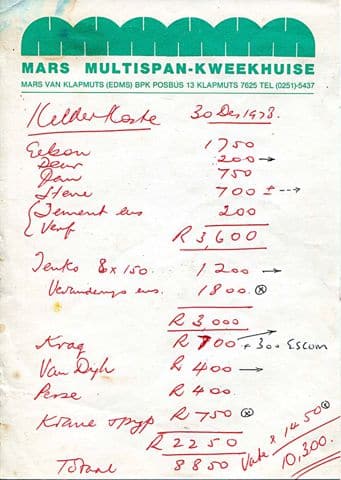

There is also a page from a notepad,dated 30 December 1978 (in Afrikaans only this time; see the photo above), on which Billy had carefully noted the costs involved in building, from scratch and with a good deal of ingenuity and financial carefulness, a small winemaking cellar. All is there, from cement and paint at R200, to taps and pipes at R750, labour, and and tanks (second-hand and of various types) and their conversion at R3000. The total: R10 300; doubly underlined.

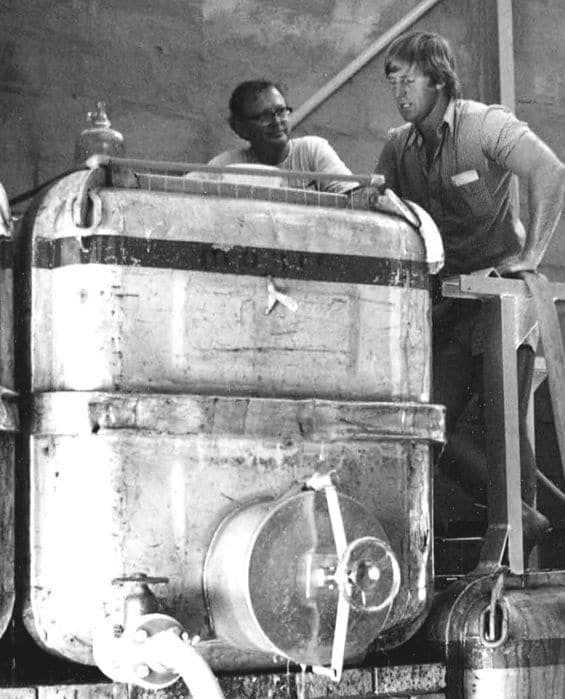

It was in those tanks that Billy, assisted by his friend Jan Boland Coetzee on harvest day as the photograph shows, made his first wines, from youthful vines – the farm now planted to an array of black grapes. The 1979 Welgemeed Estate Wine, the Cape’s first commercially released Bordeaux-style blend, was from cabernets sauvignon and franc, merlot, petit verdot (as they mistakenly thought), and malbec. It had 11.2% alcohol, though the 1980 jumped to a whopping 12.5%, these pretty much in line with the Bordeaux of the time.

The same vintage, 1979, saw another pioneering wine for South Africa – a more original and visionary one – with Amadé. This blended pinotage with shiraz and grenache, as a local take on a typical southern Rhône blend and the first time pinotage had been announced as a carefully and deliberately used component in a serious blend.

That maiden 1979 Estate Wine rated five stars in the equally infant John Platter’s Book of South African Wines. But Welgemeend, as a small and unshowy producer of moderstly oaked, understated, elegant wines, probably never received the widespread recognition that it deserved, especially for this one (later called Estate Reserve), though it was highly valued by many with palates attuned to a European aesthetic.

Billy’s untimely illness, setting in just a decade after his making those first wines, was inevitably a major blow to the Welgemeend project, though Louise (with a fine arts training) proved equal to maintaining his stylistic and quality standards. By the turn of the century, as Ursula got older and became ill, things proved more difficult to maintain; the vineyards were badly virused and infant red vines were hard to obtain; and the tragic accidental death of a worker in the cellar badly knocked Louise and robbed her of much of the pleasure of making wine. It was time to quit.

EtienneTerblanche’s comment on what he learnt about Welgemeend provides a good overview of the estate’s trajectory: “Amazing how a prominent pioneering producer has come and gone in such a short time. Also that many elements need to combine and be maintained to make it work!”

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Kwispedoor | 28 April 2025

I just loved the Welgemeend wines – from the late eighties and early nineties, especially. Their Soopjeshoogte was definitely one of the very best value wines around. I’ve long since drank them all, but recently managed to get a bottle of the 1987 Estate from Wine Cellar. I’m really hoping there’s a bit of magic left in that bottle.

Tim James | 29 April 2025

1987 was generally a light year but I remember the Estate wine lasting well and being particularly elegant. I can’t imagine it now, however. Hope it’s been very well stored. Would love a report.

Angela Lloyd | 1 May 2025

I, with some friends, had a bottle just over 4 years ago. It outshone the Kanonkop Paul Sauer ‘95 & Cab ‘01 & a rare Chateau Libertas 1968! I’ve still got a few bottles of Welgemeend, one a 198? (The label scuffed on the vital last digit!)

Barry Lambson | 29 April 2025

They were elegant and reserved wines and the Hofmeyr’s were very welcoming and humble people. The first estate I ordered wine from!

Eliria and John Haigh | 29 April 2025

John and Lil Haigh drank the 79 Welgemeend in Grahamstown courtesy of Curly Reed and were instantly enslaved. We ordered a yearly delivery from then onward. John presented a vertical tasting of 20 vintages of the Estate wine to the members of the Western Province Chapter of the Grahamstown wine Tasting Circle in the Durbanville home of Dr Andre Marais and his ceramacist sculptor wife Ann to great acclaim. Meryl and Alex Weaver and Dr. Nigel McNaught ex Stoneybrook were appreciative tasters. We may have 3or 4 bottles left in our small collection which will be shared with the Marais and our son Gregory who grew up knowing fine wine.

Irina von Holdt | 30 April 2025

I remember Billie well, hugely admired as a thoughtful and talented taster and of course, wine maker. I interviewed him in his cellar and was amazed at his collection of bottles he had made up using the formulae of various Bordeaux chateaux. They were all stored upright as he said it was quite unnecessary to lay them flat, a policy I followed after his example. I remember, too, his reply when I asked about how he had acquired petit verdot, a first in SA and a completely unknown variety. “There were just two bundles, that is 24 stokkies, on sale at the KWV and I bought them. No one else knew what they were,” he chuckled. Lovely man.

Paul Edey | 3 May 2025

This article brought back such happy memories of the Hofmeyr’s delicious, elegant wines. Am I correct in saying that some were sold on the CIWG?

Philip | 4 May 2025

Iconic and under recognised, we hosted the new owner at the Kyalami Wine Society about 10 years ago but could see that the Hofmeyer magic was no more. We loved their wines and still feel that the Cape winelands are the poorer for its passing!

paul sheppard | 17 May 2025

I had the pleasure of opening a bottle of ’86 welgemeend this last weekend – with friends from the Swartland who make wine. The wine besides being in tact and eventually quite delicious – was a catalyst to some beautiful memories and good stories of Billy and the homestead.

Francois | 23 September 2025

Thank you for the lovely article Tim. We purchased Welgemeend about a decade ago, sadly nothing could be done for the vineyards. I knew of some of the history but this piece made me realize just how special the place is. Who knows what the future may hold for Welgemeend, or Soopjeshoogte as it was first named.