There are no climate change deniers in the wine industry. When your livelihood hinges on the vagaries of temperature and availability of water, there is no doubt to how the mercury is climbing. Climate change isn’t some spectre of doom in the future, it is very much here. Just ask the producers in Champagne and their lowering acids, or over in Sancerre, where the typically light-bodied wines are getting riper every vintage.

It’s said that with global warming of 2°C approximately half of the world’s wine-growing regions could be lost, and at 4°C, around 85% will wither. To add insult, many of the surviving vineyards will also likely produce poor quality wine.

According to the recent Sixth Assessment Report from IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the temperature rising to anything above 1.5°C already spells disaster, and we could hit that by as soon as 2030. That’s right, in just 8 years. Isn’t that sobering?

So what are we doing locally if we don’t want to imbibe on the juice of burnt grapes? Long have we banged the drum of planting the right varieties in the right sites, as the vineyard is invariably more stable enjoying a longevity its poorly planted contemporaries don’t. The resulting wines from site-specific blocks are generally more delicious too, and certainly more emotive to drink. So it stands to reason instilling a culture of precision viticulture is one way to future-proof your vineyard against climatic dooms.

Enter the Gen-Z Vineyard Project, an initiative that was launched by industry body Vinpro in 2017 styled as a ‘technology transfer project’. Run by viticulturists Francois Viljoen and Emma Carkeek they oversee around 50 of what they call ‘demos’ in different regions across the Cape whereby a variety of new cultivars, clones, rootstocks, trellis systems, pruning systems, cover crops et al are all put into existing commercial blocks. The aim is to provide growers with ‘locally relevant information’ to help them make decisions. The core themes are adaptability to changing climatic conditions, cultivar suitability, efficient water use and soil health.

Emma Carkeek of Gen-Z Vineyard Project at Vinpro.

I met with Carkeek at the Welgevallen Training and Research Vineyards at Stellenbosch University, which the Gen Z team project manage. It’s an up-is-down kind of place where the laws of viticulture are treated in new and completely different ways.

There’s one block of chenin blanc with 19 different trellising systems as well as bushvines, an important grape that has already proved over hundreds of years it can weather dramatic shifts in climate. It has also shown it can retain acidity in fairly warm conditions. There’s another block with the purpose of studying pruning systems as well as the hugely important ‘fit for purpose irrigation’ block, which is looking at different irrigation strategies. “We’re trying to adapt to water scarcity,” explained Carkeek.

Higher up on the slopes is a collection of 12 different cabernet sauvignon clones planted on one rootstock. There is plenty of research going into how to preserve the variety for the future, as it is so vital to Stellenbosch’s reputation.

But the most mind-bending vineyard is the ‘Wawiel’ (wagon wheel), splayed out like its namesake with the purpose of capturing data for different row directions.

Headed by Generation Z, microcosms of all these experiments are taking place in small pockets across the Cape.

“We’re not doing scientific experiments,” said Carkeek. “You need huge capacity for them and they’re expensive. The demos are different in that they are small scale in blocks that are already commercial. They are relevant to farmers in each region.

“Findings on yield is critical, growers aren’t going to plant things that crop in small volumes. It’s completely unviable. We look at yield, we look at the growth, and we look at the juice analysis, and from certain demos, we make wine.”

Even the minutiae of vineyard poles are considered: different materials of steel, fiberglass, and cement are variously displayed.

“Steel is good as it uses less water to treat, plus the added benefit of being flame retardant – with climate change we’re certainly going to see more fires.”

Carkeek had just spent the morning at an ocean-side demo in Darling of sauvignon blanc planted on around 10 different rootstocks. The aim is to test what kinds of rootstocks do best on the dryland as well as on the poor, sandy soils. “So hopefully in a few years time we’ll have enough data to be able to identify the best performing rootstock in these kind of conditions, information that then would have more widespread use as other sites dry out.”

The West Coast is a big focus for the project, with many experimental cultivars being trialed there. In fact, Sakkie Mouton’s 2021 Sand Erf Vermentino was made from a demo block. “We want our producers to experiment with the blocks, to get involved,” says Carkeek.

“If we think about the longevity of a vineyard, you want it to last for 30 years – in that time span maybe we’ll have less rain in certain areas, more rain in others. We may be warmer in the interior, but we may not necessarily be warmer on the coast. Who knows? The most important thing is to understand your soil, the kind of climate you have and how best to manage that and to use as little water as possible. So that when the time comes when you really don’t have water, you’re already adapted to it.”

I left Carkeek in that strange, experimental vineyard with the realisation that you need to plant like climate change is already here. Use water like is already here. And in 30 years, perhaps your vineyard will survive.

One of our expectations as wine lovers is that if we spend over a certain amount on a bottle of wine, we shouldn’t have to drink it straight away. Part of the culture of fine wine is that it can improve over time, and this belief seems to run deep in the wine world.

But wine has changed, and as they say in the financial service industry when selling investment products, past performance is no guarantee of future performance. As wines generally have been made to taste better young, we really need to question the notion of drinking windows. And there are several questions that need answering, addressed in turn to each segment of the wine market.

The first is this. Does a wine built for ageing have to compromise drinkability? Second, what is it that makes a wine ageable? Third, are some people sitting too long on wines that should have been drunk some time ago? And fourth, do we need to reconsider the idea that fine wines need to be ageable?

So let’s get stuck in. First, for making an ageable wine, I think there is a need to compromise early drinkability. Some of the great old South African wines I’ve enjoyed from the 1960s and 1970s, drunk over recent years, would have been quite challenging in their youth. Picked quite early (the modest alcohol levels attest to that), they would have been taut and tannic young. But they were built to survive many decades in the bottle. I’ve had far fewer good experiences with some of the South African reds from the late 1990s and early noughties, which were much riper and approachable on release. Picking later seems to compromise ageworthiness. Most of these wines had survived 10-15 years’ cellaring, but hadn’t improved, and were a bit mushy with age. Bordeaux, the world’s most famous fine wine region, has been on a similar journey with ripeness. Everyone assumes top Bordeaux reds are candidates for 50 years in the cellar. But look at the 2009s, for example: tasty on release, but I’d watch their evolution carefully if I was using them as an investment vehicle. And I was at a Ceretto (Barolo) vertical last week where Federico Ceretto said that climate change had changed Barolo, and these weren’t 40-year wines any more but 20-year wines, and they tasted much better on release.

This leads us on to the question about what makes a wine ageable. Wine chemistry lags behind peoples’ experiences here: you can’t really analyse a wine and then read out a drinking window. In general, though, tannins and other polyphenolic compounds help a red wine age longer. Lower pH also helps reds and whites age (which means that high acidity correlates with ageworthiness. But this could be correlation, not causation, at least in part: if you pick earlier your wine will have more acid, and picking earlier also correlates with ageworthiness in whites and reds. Lower pH also helps SO2 work more effectively, and SO2 also helps a wine age. A long élevage also helps make a wine age better: more time in barrel or foudre before bottling seems to make whites and reds better able to survive in bottle. With whites, oxidative juice handling that allows the phenolics to fall out seems to set the wine up best for longer ageing. And cellaring at cool temperatures also helps wine age gracefully.

This raises the question of whether we really need to have wines that are capable of long ageing these days, when so few have proper cellars? The answer to that question is answered when you taste a well-cellared great old bottle – yes, we do want wines that can age. It’s part of the joy of wine. But maybe we need to rethink the way we approach fine wine. Rather than assume that all fine wines can age, we need to think that those that have the potential for long ageing are the exceptions, not the norm. While most of our drinking will be of bottles with short-ish windows, there are going to be a certain number of classically structured fine wines that we need to cellar, and which have the potential for long ageing – the potential not merely to survive, but to develop positively in the cellar. There’s no doubt that now many very good wines are being kept beyond their peak drinking window, and I think this is a shame. People buy wine that’s reasonably expensive, and stash it away, and don’t get round to drinking it when they should.

I think that there is this unwritten contract that when you buy a wine over a certain price, it’s good for – say five years? – cellaring at least. Maybe we should re-think this? One of the joys for me as a wine drinker has been the emergence of the natural wine movement. Here, I suddenly got to drink ethereal, complex, aromatic red wines with many of the characteristics of well-cellared old wines but on release. These are not wines I’d have any inclination to cellar (although I realise here that there is a vast diversity of natural wines, and I’m making a generalization, and even some no-added-sulfite wines do have the capacity to age) but rather pop them straight away when I’ve bought them and really enjoy their complexity and elegance. This has changed the restaurant experience for me. It’s not just the natural wines, either: there’s now a host of beautifully fragrant, elegant, lighter-coloured infusion reds on the market that taste beautiful young. No longer do we have to open sturdy, built-for-ageing reds too young in their life when we dine out. We can drink young fine wines at their peak. This works for everyone: a lot of young winegrowers are making wine, releasing it in two tranches the year after it is made, getting cashflow, and customers are buying them, drinking them, and then coming back for more.

So I’d say drinking windows are getting shorter at one end of the market, and at the other, with a move back from picking later, they are getting longer. And we are moving to a more functioning system of fine wine.

96/100.

Here are our five most highly rated wines of last month:

Boekenhoutskloof Stellenbosch Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 – 96/100 (read original review here)

Kleine Zalze Project Z Chenin Blanc 2019 – 95/100 (read original review here)

Pieter Ferreira Blanc de Blancs Cap Classique 2015 – 95/100 (read original review here)

Boekenhoutskloof Franschhoek Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 – 94/100 (read original review here)

Kleine Zalze Project Z Sauvignon Blanc 2020 – 94/100 (read original review here)

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

Looking recently for something to drink in the semi-chaos of a wine fridge (I seem incapabable of updating records, and this cooler needs a thorough sorting and listing as soon as the weather allows having the door open long enough) I noticed a Leeuwenkuil Heritage Syrah 2013. Not likely to be near its peak but should be both lovely and interesting, I thought.

It was the second vintage of this wine off a hitherto rather neglected Kasteelberg (Swartland) vineyard, made in the early years by Rudiger Gretschel at Reyneke. The maiden 2012 had been rather overbright and stalky, but the 2013 had had more fruit depth, though it too was redolent of dry stones. It still did last week and in fact was more interesting than lovely on the first night, but improved and rounded itself out nicely for the second.

The experience made me think that it might be good to try a few more of the new wave of Swartland syrahs that were emerging around this time with notably lower alcohols (12–13%) than we’d found previously in the likes of Sadie and Mullineux. Also, and thus, a pronounced freshness, often with at least some wholebunch pressing. Much credit for this development in the Swartland must go to Craig Hawkins then making wine at Lammershoek – where, whatever the problems (and there were some) he definitively established that earlier picking was a more plausible and potentially rewarding strategy than had been deemed likely.

So I rummaged around and settled on four light and bright Swartland syrahs – two from the famous 2015 vintage, two from the early drought year 2016. Old enough to make it interesting to see how this style of syrah was developing as it started to approach maturity. There has been some wondering about whether the lighter style would age well. So far, at six and seven years age, things are looking good. All four of these would benefit from further cellaring I’d say – especially judging by how much they gained from substantial aeration, even a day or two in open bottles.

Readiest to drink is the Blackwater Cultellus Syrah 2016 (MMXVI as the label has it). But I suspect that might always have been the case, for this is the lightest of the four tasted last week, the only one indicating just 12% alcohol. It was was first made in 2011 by Francois Haasbroek while he still had his day job at Waterford. There’s charm and character and freshness and, tellingly, it was the first bottle to be emptied in the hot days of last week. But the undoubted loveliness of flavour did have a touch of dilution and lack of complexity, I thought. A touch more grape ripeness would have improved things.

The other 2016 was the Swerwer Shiraz, the first solo appearance of the grape from JC Wickens. Swartland-typical dryland bushvines, minimalistically made (like all these), made partially with whole-bunch fruit – which comes through clearly on the bright, red fruit perfume and flavour. There’s still some primary fruit there, and this is a most lovely wine. It’s velvet-textured, with the firmest tannins of this quartet – but these typically Swartland in their meltingness – and fresh and pleasingly un-heavy at an indicated 13% alcohol. I don’t actually want to say “light”, because it’s only that in relation to heavier, more extracted and riper wines. Elegant will do fine to indicate the balance.

The two wines from the famously easy 2015 vintage had perhaps more intensity. Leeuwenkuil Heritage Syrah was definitely better than the 2013 I’d tried – no doubt showing the benefit not only of the vintage but the vineyard having been well looked after for a few years. Perfumed, with some darkness of fruit added to the bright red, and a silky richness; with an exciting note of dried herb-fynbos savoury austerity. Softly firm tannins, but I felt the wine to be particularly youthful still and deserving more years to bring it into greater harmony. Excellent stuff, but I certainly will hold my other few bottles for five years at least.

Terracura Syrah 2015 (the maiden vintage) was assembled by winemaker Ryan Mostert from half a dozen vineyards, vinified in typical hands-off fashion; with, obviously, like the other wines here, only older oak elevage. Readier to drink than the Leeuwenkuil but just as fine, I reckon. Floral, spicy and succulent, the fresh acidity and informing but unassertive tannin structure beautifully balanced and already seamless. Gorgeous wine and would probably get my vote as the winner of this quartet on the day. Try it now if you have a few bottles, but I think it too will benefit from further ageing.

So much for a handful of new wave Swartlanders in their early adulthood. They were made at the time when a new fresh, unwoody style of Stellenbosch syrah was on the horizon. Reyneke (under the guidance of Rudiger Gretschel) was already doing exciting stuff along these lines and I’d thought of including the great 2015 Red Reserve (pure syrah) and the Biodynamic Syrah in my little lineup. But these can wait for a few other Stellenboschers, like Reenen Borman (Boschkloof and especially Sons of Sugarland) and Lukas van Loggerenberg, to join them as another demonstration of just how splendid new-style Cape syrah can be, and how it promises to develop well with some maturity.

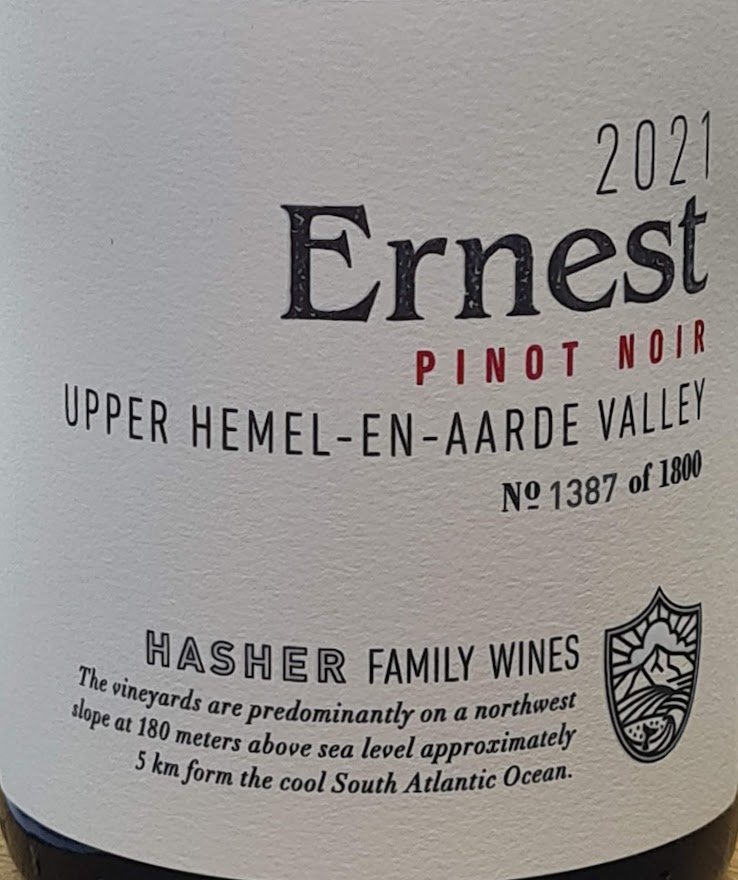

Céline Haspeslagh and Frederik Herten of Belgium acquired Upper Hemel-en-Aarde Valley property Sumaridge last year and have renamed it Hasher Family Estate (Haspeslagh comes from a family with significant interests in the agricultural sector and her uncle Xavier is a co-investor).

Plantings of vineyard have been reduced from 35ha to 19ha and the focus will be predominantly on Chardonnay and Pinot Noir going forwards – viticulturist Dean Leppan has come across from near-by Newton Johnson Vineyards and Walter Pretorius stays on as winemaker.

Tasting notes and ratings for the maiden releases as follows:

Fat Lady Sauvignon Blanc 2021

Price: R145

30% barrel fermented and matured for six months in older oak. Citrus and a hint of blackcurrant on the nose while the palate is rich and round with well-integrated acidity – not nearly as obtrusive as some of examples of this variety can be.

CE’s rating: 90/100.

Marimist Chardonnay 2020

Price: R380

85% fermented and matured for nine months in 228-litre barrels, 20% new. Citrus and yellow peach plus overt oak and spice on the nose. Surprisingly full given an alcohol of just 12.5% – plenty of flavour but somewhat unknit now.

CE’s rating: 91/100.

Ernest Pinot Noir 2021

Ernest Pinot Noir 2021

Price: R450

35% underwent spontaneous fermentation. Matured for 11 months in 228-litre barrels, a third new. Appealing aromatics of red currant, cherry, musk, tea leaf and white pepper. The palate is medium bodied with pure fruit, fresh acidity and fine tannins. Good detail, the finish possessing a pleasant salty quality.

CE’s rating: 93/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

It doesn’t get more typical of Stellenbosch than the Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 from Delheim. Matured for 14 months in 300-litre barrels of which 45% were new, the nose shows cassis, some leafiness, turned earth, vanilla and spice while the palate is full-bodied with dense fruit, fresh acidity and pleasantly firm tannins, the finish long and savoury. Price: R220 a bottle.

It doesn’t get more typical of Stellenbosch than the Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 from Delheim. Matured for 14 months in 300-litre barrels of which 45% were new, the nose shows cassis, some leafiness, turned earth, vanilla and spice while the palate is full-bodied with dense fruit, fresh acidity and pleasantly firm tannins, the finish long and savoury. Price: R220 a bottle.

CE’s rating: 91/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

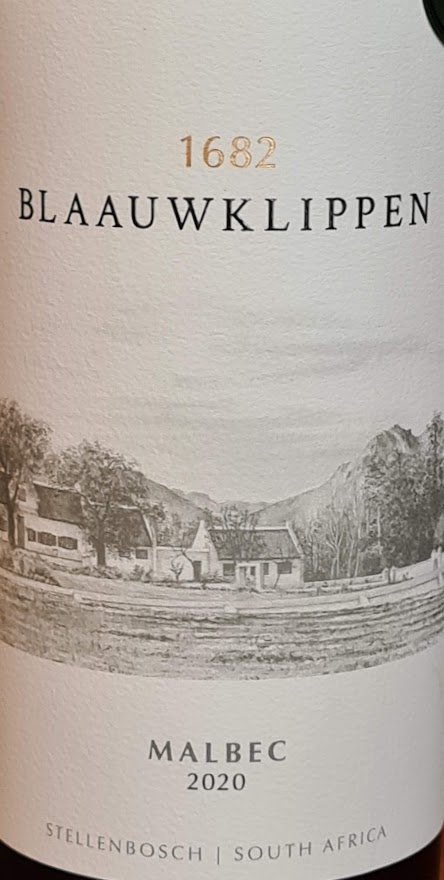

“Is SA Malbec on the rise?” asked columnist Greg Sherwood MW recently and the 2020 vintage from Stellenbosch property Blaauwklippen suggests that he’s not wrong to draw attention to the variety.

“Is SA Malbec on the rise?” asked columnist Greg Sherwood MW recently and the 2020 vintage from Stellenbosch property Blaauwklippen suggests that he’s not wrong to draw attention to the variety.

Attractive aromatics of red and black berries, floral fragrance, fresh herbs, pencil shavings and oak spice precede a palate that has great fruit definition, bright acidity and fine tannins, the finish nicely dry. Not insubstantial at 14.73% alcohol but wonderfully clean-cut and well-weighted (maturation lasted 12 months in 300-litre French oak barrels, of which 23% were new). Price: R145 a bottle.

CE’s rating: 93/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

It’s almost as if all that was required was one flick of the magic anti-pandemic wand and all would be back to normal again. Well, that is certainly how the past few weeks in the London wine trade have felt where tastings with producers and importers have seemingly returned to almost pre-pandemic normality. Thankfully, South African producers have also slowly been filtering back into London after a nearly two year travel hiatus for most. For those that have already managed to venture back to the UK, they will almost certainly have been met by an endless procession of positively jubilant wine merchants, many of whom will have enjoyed one of their most successful years on record for the 2021 business year.

Certainly not without its challenges, especially when it came to importing wines into the UK from almost anywhere in the world, especially from the EU, the year did somehow progress positively and consumer demand for fine wine has seemingly never appeared stronger or more buoyant. Indeed, earlier this week, I had a wonderful opportunity to catch up with Andrew Gunn, owner of the well know Elgin winery Iona, to taste a line-up of his new releases over lunch and generally chew the fat, discussing the ups and downs of both the UK and South African wine industries over the past two years.

Quite interestingly, one of my very last producer tastings with a winemaker / wine owner back in early March 2020, just before national covid lockdowns were instituted and international air travel suspended, was with Rosie Gunn, Andrew’s wife. It’s quite fair to assume that the more introverted Rosie would more than happily have stayed back at home on the farm in Elgin, however just before he was due to travel to Europe, Andrew had fallen off a ladder on the farm and broken several bones, rendering his ‘travel credentials’ temporarily out of order and thus thrusting Rosie into emergency backup marketing duties.

Andrew is of course not a foreigner to Europe and indeed Piedmont in Northern Italy, where he and Rosie own a small property together. And if there ever was a very fragmented, subdivided, complex network of villages and appellations within a region, Piedmont is the perfect example making even the intricacies of the North to South Burgundian appellations of the Côtes de Nuits and the Côtes de Beaune seem almost elementary in comparison. Piedmont is a complex moonscape of villages, hill tops and valleys that make up some of the most wonderfully famous regions like Barolo and Barbaresco. Complexity is certainly one of the regions calling cards and is not easily understood or interpreted within the context of wine styles and wine quality without one actually visiting and spending a certain amount of time in the region driving around and walking through the famous vineyard sites.

But is all this complexity absolutely necessary? Is it required to engage with the consumer on a more intricate level? Chatting with Andrew, it became clear that as an engineer, he is big fan of intricacy and when it came to his own home region of Elgin in the Cape, he was very keen to subdivide the region further into additional wards such as the Elgin Valley and the Elgin Highlands, where the Iona wine farm is located. In many ways, creating these layers of intricacy and complexity within an appellation or region is one of the best ways to facilitate greater engagement with consumers, particularly the more involved fine wine collectors, buyers and lest we forget, drinkers.

But it nevertheless remains one of the great conundrums of the wine world. How much complexity is required to engender a deeper, more beneficial level of engagement with consumers? This was of course a debate that raged for years amongst the producers of the greater Hemel-en-Aarde Valley in Walker Bay before they decided to subdivide the region into the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley, the Upper Hemel-en-Aarde Valley and the Hemel-en-Aarde Ridge. It has been several years now since these changes were put in place, but I think whoever was the driving force behind the original idea can feel fully vindicated as more and more producers within each of the three differentiated wards produce increasingly more individual and different expression of primarily Chardonnay and Pinot Noir.

While many of the wine regions of Europe may have been delineated decades, if not hundreds, of years ago, a similar debate about creating more intricacy and differentiation still surfaces in many of the continent’s most famous wine growing areas. The most current debate that is still raging must surely be in Brunello di Montalcino in Tuscany, where certain enthusiast seem adamant that the small square that is the Brunello DOCG appellation, should be divided into four sub-zones in the north, east, south and west, to further help differentiate the styles of Rosso and Brunello di Montalcino coming out of wineries in these diverse and disparate areas. As an avid Brunello wine lover, a wine scholar and a highly engaged wine consumer, I think it’s a fantastic idea.

These debates seem destined to rage on all around the world including increasingly in the Western Cape winelands, with proponents and opponents arguing the merits of more complexity versus more simplicity. But ultimately, all that one needs to understand is that layered and scaled levels of intricacy and complexity in the wine landscape merely need to be made available to consumers on an opt-in and opt-out basis and then they will decide how far and how deep they want to immerse themselves into any given wine journey. Why deny those keen to engage on a higher level… so long as no one forces others content to merely drink the stuff in order to register their full enjoyment on their own simple pleasure scale?

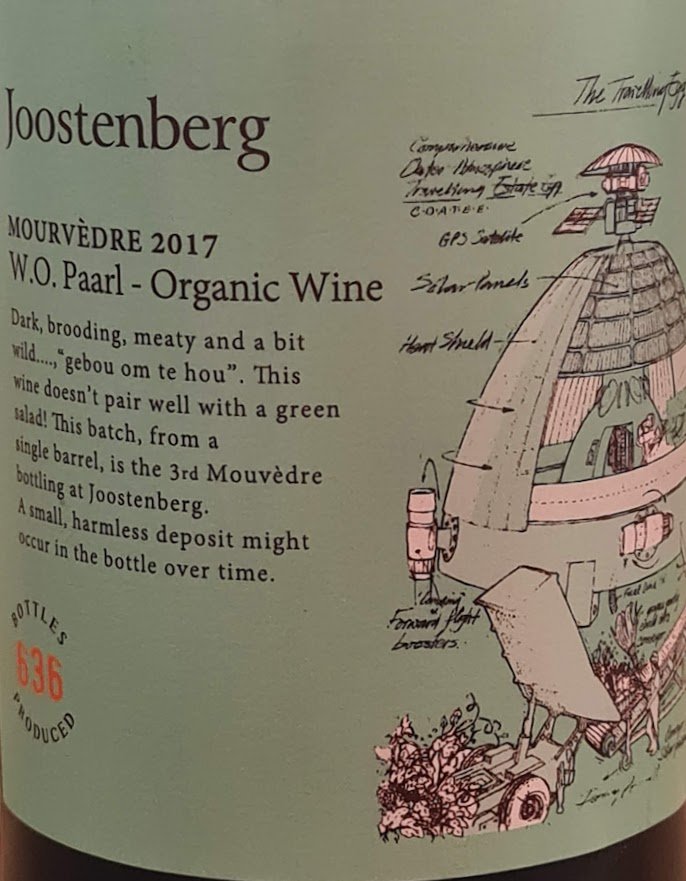

Grenache gets all the airtime but at the end of 2020, there was slightly more Mourvèdre planted locally – 495ha compared to 477ha at the end of 2020, making them 19th and 20th most widely planted varities in the country respectively.

Mourvèdre is probably never going to be a huge commercial success as it can often have a gamey, almost animal scent but my sense is that it tends to fare well under local growing conditions producing wines of good fruit intensity and structure.

The most recent single-variety example I’ve come across is the Small Batch Collection No. 21 Mourvèdre 2017 from Joostenberg in Paarl and again it’s smart. From a 17-year-old vineyard farmed organically, winemaking involved 30% whole-bunch fermentation before maturation lasting 10 months in a single, previously used 500-litre barrel.

The most recent single-variety example I’ve come across is the Small Batch Collection No. 21 Mourvèdre 2017 from Joostenberg in Paarl and again it’s smart. From a 17-year-old vineyard farmed organically, winemaking involved 30% whole-bunch fermentation before maturation lasting 10 months in a single, previously used 500-litre barrel.

The nose initially shows dark berries, a slight meatiness, earth and spice but notes of red berries and dried herbs emerge with time in the glass. The palate, meanwhile, has good depth of fruit before a finish that’s long and dry. It’s a wine that’s not slight but equally does not come across as sweet or hot – it carries its 14.5% alcohol well. It’s also no longer totally primary but should drink well for a few more years even so.

CE’s rating: 92/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

Tasting the Kleine Zalze Project Z Chenin Blanc 2019 next to its Skin Contact counterpart recently raised all sorts of questions about what is fundamentally at stake when it comes to wine assessment and appreciation.

The two wines come from the same old Firgrove vineyards, grapes picked at the same time, and both were fermented in amphorae, with the only difference between them being that the former received 12 hours of pre-fermentation skin contact while in the case of the latter, fermentation included a seven-day period on the skins.

My initial impression was that for all the Skin Contact’s flavour and texture, technique was obscuring variety and site. The more conventional bottling had greater purity of fruit and overall harmony and therefore seemed the “better” wine.

My initial impression was that for all the Skin Contact’s flavour and texture, technique was obscuring variety and site. The more conventional bottling had greater purity of fruit and overall harmony and therefore seemed the “better” wine.

The stark juxtaposition of the two wines was leading me into some problematic binary thinking, however. Traditionally, we regard wine assessment as an analytical and quasi-scientific activity where any one sample is looked at in terms of correctness in the sense of freedom from flaw or fault. This is premised on the notion that with sufficient training, a taster can at the very least discern the winemaker’s intention (the winemaker’s purpose in creating the wine) or at most the impact of terroir (the notion that wines taste of “somewhereness” and that some sites generate more profound drinking experiences than others).

If you think about it, wine appreciation is riddled with binary opposites. There are some that are technical such as dry/sweet and reductive/oxidative but then there are those that are more allegorical such as elegance/power or lean/plush and then those that are outright political such as Old World/New World or masculine/feminine.

These binary opposites, and the stability of meaning that they supposedly facilitate, help to maintain the grand narrative of the established wine trade. Old World is better than New World; structured wines are masculine rather than feminine and therefore more age-worthy and investable and so on…

In particular, developed country gatekeepers insist a deep knowledge of first-growth Bordeaux and grand cru Burgundy and the like is essential in order to partake in the dialogue concerning fine wine precisely at a time when prices for these wines put them well beyond reach for most of us in so-called emerging markets.

The good news is that there aren’t any certainties and meaning is inherently unstable, whether it be wine or anything else in life. It’s perfectly possible, for instance, to have a wine showing both volatile sulfur compounds (reduction) and oxidation and equally for one person to like such a wine and another not to. Arriving at the definitive valuation of wine is nonsense given that stemware, serving temperature, ambient light, background noise and so on can all affect one’s judgement. Enjoyment, in turn, can be influenced by the assembled company and the food pairing.

What of the way forward? Being able to describe the sensory qualities of wine – visual appearance, aroma and tactile presence in the mouth – will always be important lest we descend into utter relativism. However, how the wine makes you feel is also vital in the same way that listening to your favourite composer is emotionally moving in a way that entirely transcends being able to read music.

As for who gets to participate, not having access to the most expensive wines in the world does not automatically nullify anybody’s ability to pass comment – the world of wine is vast and there is plenty of room for everyone.

Also important in extending the wine community is to focus on how the wine came into being – the people and the process that produces the wine. This comes down to storytelling and an effort to connect consumer with creator towards a shared human bond (a massive amount of the appeal of the Project Z from Kleine Zalze is that a big winery is prepared to undertake experimental winemaking and do so successfully).

Lastly, there are some binary opposites that really are unhelpful and need to be dismantled. If you still think “masculine” and “feminine” are useful as wine descriptors, then you’re out of touch.