When will Oldenburg, situated in the prime Banghoek area of Stellenbosch, deliver on its true potential? The current releases of its top-end wines are pleasing enough but could do with more character and individuality. The accomplished Nic van Aarde, previously of Warwick, started there in late 2018 and it will be interesting to see what he can achieve. Tasting notes and ratings for the Rondekop range of wines as follows:

Oldenburg Rondekop Stone Axe Syrah 2017

Price: R390

Matured for 20 months in French oak, 50% new. Red and black fruit plus vanilla with a little floral perfume in the background. Dense, sweet and smooth textured on the palate. Splendidly decadent or overdone and tiring to drink? You decide…

CE’s rating: 89/100.

Oldenburg Rondekop Rhodium 2016

Price: R390

60% Merlot, 20% Cabernet Franc, 10% Malbec, 10% Petit Verdot. Matured for 18 months in French oak, 100% new. Red and black fruit, a herbal note and toasty oak. Medium bodied with fresh acidity and fine tannins. A solid rather than inspired rendition of a Cape Bordeaux red blend.

CE’s rating: 90/100.

In and of itself.

Oldenburg Rondekop Per Se Cabernet Sauvignon 2016

Price: R450

Matured for 18 months in French oak, 100% new. Cassis, some leafiness and attractive oak-derived notes. Rich and full but nicely balanced. Smooth textured in the best sense, the finish long and dry. Proof once again that Banghoek is Cab country.

CE’s rating: 91/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

Attention: Reviews like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

It’s almost with guilt that I’ve been enjoying the gorgeous weather here in the Western Cape – the sunshine has made suburban lockdown so much pleasanter than it would have been with drear dullness, cold and wet out there. A little decent rain a few weeks back, and the merest trickle since then, amidst an unseasonably long run of warm and bright days in April and early May. What’s to complain about in a golden time like this – more late summer than the autumn that should have arrived?

Guilt? Well, at the least some nervous apprehension in sympathy for winegrowers seems appropriate, given my now notional involvement with the industry that’s still happening out there in the real world. The drought that afflicted us for three years was partly broken last year, but certainly not definitively so, and signs of winter rains arriving would be paradoxically cheering. Winter cold too, to urge the vines into their dreamless, restorative sleep. And then a few days back I received some pictures from Eben Sadie, showing compost being broadcast over the vineyards on his Paardeberg farm. I was startled to see how green the vines still were under those blue skies – unsurprisingly so, I then realised, given the reluctance of autumnal conditions to arrive. Of course, I haven’t set eyes on a real live vineyard for at least six weeks.

The crucial task for most grape farmers at this time of year is (in addition to enriching the soil if necessary, as on Sadie’s Slangdraai vineyard) sowing the winter cover-crop. Ideally, that needs rain to encourage germination. Is the lovely weather proving a worry to winegrowers, in addition to all the pandemic-imposed problems of April? A phonecall revealed that it was not, in fact, a problem to Carl van der Merwe of DeMorgenzon in Stellenbosch. Carl’s cover crops had actually gone in before the rain, so all was well in that respect. He confirmed that “leaf fall has been very much delayed” by the warmth, but even here he could look on the positive side, thinking of all the photosynthesising still going on, building up the vines’ reserves. (Other news is forthcoming regarding Carl and DeMorgenzon, but that too is shut down for now…).

Incidentally, Carl also sketched me a picture of the busy farm and winery under Covid19-imposed conditions, with the team in masks, after their temperatures were taken on arrival at work to ensure that no-one was feverish. Let’s hope everyone out there in the Cape Winelands is being equally careful, and wish them well as they work.

If DeMorgenzon is fine, viticulturist Rosa Kruger confirmed for me that for the very many farmers who hadn’t done an early cover-crop sowing the too-clement weather is indeed proving a problem. There seem to be, what’s more, at least another few weeks of sunny warmth to come, and for a while, it’s getting even hotter. Most farmers will wait another week or so for their cover crops but, Rosa says would be very reluctant to plant after the third week of May.

Uncertainty about labour availability under different government lockdown regimes is making many farmers nervous, Rosa says, and pushing them to get things done. The first pruning might be pushed forward as a result, she says, even before proper dormancy has set is, because of a fear that there might be a lack of pruners if tighter regulations are returned to.

Rosa is also clearly depressed and worried about the effects in the Winelands of lockdown and restrictions on the wine business. VinPro (admittedly seldom keen to present a rosy view of farmers’ prospects) is apparently forecasting widespread financial failure amongst farmers by the end of the year. Undoubtedly farmworkers are already suffering. Wages are being cut, Rosa says, and there are retrenchments. Contract workers are particularly feeling the tightening; Rosa knows of just one contract viticultural team at work, of the more than half-dozen that should normally be active at this time.

Another beautiful day was dawning in Cape Town as I took my dogs for a walk around the suburban streets today. And dawning too across the beautiful Winelands. If only I could plausibly wish myself the sunshine and, for the vines, plunging temperatures and dark rolling clouds bringing rain.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

The current conversation around Coronavirus and its effect on the South African wine industry is perhaps inevitably very emotionally charged.

We put the same set of questions to a variety of industry stakeholders with a view to obtaining a better understanding of what’s happening on the ground and also plotting a way forward.

Chris Alheit of Alheit Vineyards.

First to respond was Chris Alheit of Alheit Vineyards. He added the following proviso: “I’ll answer what I can, but obviously I’m just a winemaker, not an economist or an actuary. Plus I truly respect our president, but find the current decision making impossible to reconcile with logic.”

How badly has the Coronavirus crisis impacted your business?

The magnitude of the impact is yet to be seen. We are largely an export business, and the European/American/Asian restaurant scene that our wines feed into has been hugely affected. The entire ecosystem both locally and abroad that our wines feed into has been damaged. Most of our importers are very strong, but even so, we’ll have to see what kind of allocations they commit to in light of the new restaurant landscape. I do however remain very positive due to one fact: people want to drink nice wine, and top-end SA wine provides brilliant value in comparison to many other countries’ top-end offerings. Let’s hope I’m right. The other side of that coin is that if people have limited funds they will spend their money on the classic regions that they know instead of branching out into SA wine. Aside from that, we have experienced significant delays in receiving packaging material. This will further delay our income stream.

How many wineries do you foresee closing as a result of the pandemic?

I have no idea, but it will not be a handful.

What plans do you have in place to get going again once restrictions are eased? How will doing business be different?

I think we need to brace for impact, be careful with our money, and keep on finding ways to improve our direct sales. We have a solid mailing list, and we plan to make being on our mailing list really worthwhile by offering once-off wines, and best possible prices on our main wines. I think the silver lining here is for us to find better balance by being a bit less dependent on the wine trade, and a bit more involved in direct sales. Obviously we have great friends in the trade that have supported us from the outset, and I think the trade will bounce back, but having a stronger direct sales leaning makes a small business like ours less vulnerable in times like this.

What will the South African wine landscape look like after the pandemic? Will the industry recover quickly or will it be changed forever?

Again, I have no idea. I do think that this time will leave its mark for a while to come, but I’m not qualified to quantify the length of breadth of the disruption.

David Clarke of the agency Ex Animo Wine Co. provides a podcast consisting of a series of interviews with industry figures, a recent subject being Eben Sadie of Sadie Family Wine. Listen to it here.

David Clarke of the agency Ex Animo Wine Co. provides a podcast consisting of a series of interviews with industry figures, a recent subject being Eben Sadie of Sadie Family Wine. Listen to it here.

“There was no hope that a government, so strongly influenced by the prohibitionist faction, would ever consider the grant of special bounties to the winegrowers.”

“There was no hope that a government, so strongly influenced by the prohibitionist faction, would ever consider the grant of special bounties to the winegrowers.”

Words not written during South Africa’s coronavirus lockdown, among the strictest in the world with its ban on domestic alcohol sales, but by physician, poet and playwright C Louis Leipoldt in his 300 Years of Cape Wine, first published in 1952.

He was describing the ‘period of great hardship and much distress’ for winegrowers that followed the Anglo-Boer War and led to the formation of South Africa’s first co-operative cellars from 1906 onwards, a result of wine farmers showing ‘praiseworthy self-reliance’ rather than asking for government bailouts – perhaps a story for next time.

Needless to say, the ‘prohibitionist faction’ bit struck a chord in light of our police minister (among others) reportedly expressing the wish that the booze ban could be extended beyond lockdown. And then I saw that Leipoldt had written an entire chapter entitled “Restrictions and Prohibitions”…

For the first 250 years or so of Cape wine, noted Leipoldt, ‘there was no vestige of any desire to inflict unnecessary restrictions… The Cape was a wine-producing country, the oldest in the empire, and its community had from the days of Van Riebeeck learned that wine was of food value and that light wine, while it gladdened the heart of men, was never a communal danger.’

There was ample evidence to support this statement, insisted Leipoldt: ‘Wine was drunk in every family; it was given to the coloured servants as a matter of course; to children at school and to children at home; as a ration to the soldiers, and even to sick convicts. It was extensively used in the home; all the old Cape cooks thought it indispensable for the making of their dishes.’

As I discovered in my last column, brandy was given to slave children who attended school in the 1650s; now Leipoldt revealed that Bishops boys had always received a glass of wine with their midday meal: ‘Old pupils of the Diocesan College state that this custom prevailed in that institution, and that no parent ever objected to the custom. In every middle-class family, in town as well as on the farms, wine appeared regularly on the table at the midday meal, and all children belonging to such families learnt to drink wine.’

Leipoldt was, therefore, scathing of increasingly restrictive legislation that, by the 1950s, had resulted in ‘compulsory prohibition for practically three-fourths of the population of the country’ (i.e. only ‘Europeans’ or white people were now permitted to purchase and consume wine). He said that the prohibitionists’ propaganda was ‘masking its innate illiberalism and intolerance under the guise of charitable concern for the interests of the non-European’ and that to claim that wine was ‘not only a luxury but a deadly and insidious poison that it is the duty of the state to suppress’ (i.e. among black people) was ‘blatant hypocrisy’.

‘The present unfortunate situation is an absurdity from whatever point it is looked at,’ concluded Leipoldt in the final chapter of his book, entitled The Future. ‘The wine farmer is, by implication, stigmatized as the maker of a food product that three-quarters of the population is debarred from using; for a native to use that product is a crime; for a white man to supply him with that product, even in his own home, is equally a crime. The logical conclusion is that if that product is so frightfully poisonous to everyone who is not fortunate to be in possession of old red sandstone hue, its makers should be prevented from making it at all. That is a conclusion and an implication which the winegrower and the merchant should not submit to, and it is wholly in their interests to expose the fallacy that underlies both…

‘We have little reason to be proud of some of the laws that have been placed on our statute book since Union,’ he went on, ‘but there is none so laughably illogical, so flagrantly undemocratic, so ferociously racial and, let it be added, so egregiously inept as that which regulates the sale and purchase of wine. […] One may point out that every attempt at prohibition in South Africa, which has now been tried since 1851, has been a miserable failure; every year the number of convictions for illicit liquor selling increases, the illicit trade prospers…’

I wouldn’t say that Leipoldt was entirely above reproach. For example, so convinced was he that ‘natural wine is a food, a valuable dietetic adjunct’ that he argued against abolishing the dop or tot system on Cape wine farms (a ban duly imposed in 1960 but only enforced in the 1990s). ‘The wine ration given to French and Spanish soldiers in Africa was found to be of great dietetic value, and the reasoned report of the committee of French experts who studied the matter has, so far as I am aware, not been invalidated by subsequent investigations,’ he wrote.

Nonetheless, this is what he concluded about prohibition: ‘In every wine-producing country every citizen, irrespective of age, class, sex, colour of skin, occupation or standing, is allowed to purchase and drink pure natural wine, and in no wine-producing country except South Africa, where such free purchase and consumption is illegal for ninety per cent of the citizens, is drunkenness and the crimes that drunkenness engenders, alarming or excessive.’

Are South Africa’s crime levels down because of the lockdown? Undisputedly. Are they down because of the alcohol ban? History suggests otherwise.

Either way, Leipoldt concluded: ‘If the present absurd legislation remains on the statute book, the production of natural light wines will hardly develop sufficiently… No one who loves South African wine and who has at heart the interests of the industry would like to see that happen in a country whose natural wines should be regarded as a national asset and a communal boon.’

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Leipoldt, C Louis: 300 Years of Cape Wine, Tafelberg, 1974

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

Francois and Lida Smit, who own Leipzig, situated in the Nuy Valley outside Worcester, decided to start making wine under their own label again in 2013, ending decades as a grape supplier to Nuy Winery.

Of the Cape.

White Leipzig originally featured in the 1940s and was even served to the British Royal Family on their 1947 visit to South Africa. Now that the cellar is again producing, a white blend was an obvious inclusion in the portfolio.

From Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc and Viognier and matured for nine months in old oak, the nose shows honeysuckle, citrus, peach, vanilla and spice plus some leesy complexity while the palate is rich, full and flavourful. Price: R144 a bottle.

CE’s rating: 89/100.

Check out our South African wine ratings database.

Attention: Reviews like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

Unlike the rest of the world, South Africa’s lockdown closed wineshop doors to admirers of the vinous arts. Like most of the cultural world, our art museums and galleries too turned patrons away. The result, to hold up a viral cliché, is #thingswillneverbethesame.

Most of the art world has taken the switch to digital just a little quicker than the inevitable: making collections and exhibitions virtual – 3D-streaming, video ‘tours’ and on-line lectures and demonstrations. It’s not new, just implemented a tad sooner and more circumspect since there was no more income to be taken at the door. (This is another conundrum of support and sustainability that the great cultural institutions face: check out the Baxter Theatre’s predicament and that of the Cape Town Philarmonic Orchestra.)

But this artificial reality of art (a lovely, philosophical multi-paradox, if you wish!) – this second-hand experience of painting, sculpture, print, photograph, performance in real time, in the real spaces of great, old museums and beautiful contemporary architectural dream buildings – started the minute those purveyors of the revolutionary mobile phone had the bright idea of adding a camera to gizmo.

It took over the tourist art museums when another bright spark, tapping the basics of human nous, created (if that is the right word) the ‘selfie’. Oh, to be seen with Picasso. Or Monet. Or Tretchikoff. (A pilgrimage to a famous masterpiece in a great museum will, these days, often mean engaging with hordes looking at that artwork through the telephone screen, foregrounded by whoever is clicking.)

So are art lovers missing their art during the lock-down? Are wine lovers missing a trip to their favourite wine store, cellar tasting room?

In an #artwillneverbethesame piece last month, The Washington Post’s distinguished art critic, Philip Kennicott, contemplates how long it will take before we once again enjoy art “as a form of social bonding”. He argues strongly that, with museums shut, we should revisit the singular experience of an artwork.

“Throughout the history of the arts … there has been a recurring belief that the best art, the truest and meaningful, is made apart from the world. Artists need distance to create. They need independence and isolation to free themselves from the conceits of fashion and the desire to please.”

Substitute ‘art’ with ‘wine’ and consider our current experience of the joys of wine.

Like an art critic, Winemag’s editor Christian Eedes, in his professional status as locked-down judge, probably gives full weight to the silence and space for making an evaluation. Tim James to likes drinking alone.

Kennicott defines it as “the power of private contemplation and solitary engagement. The silence in the room … the presence of your undivided attention”. (He was, one would imagine, reflecting on physically real work and not its on-line ghost.)

But, as I’m sure Christian will be first to agree, the real pleasure of what’s inside that 750ml bottle of wine is to share it, and “to say to others, ‘Here, look at this’”. Otherwise, what’s the point of being a judge anyway.

If ‘Here, taste it…’ is a futile gesture in the tyranny of isolation, consider the conundrum art and artists faces.

In an entertaining article also considering #artwillneverbethesame The New Yorker’s colourful art critic Peter Schjeldahl recently gave these virtual art shows short shift: “Online ‘virtual tours’ add insult to injury, in my view, as strictly spectacular, amorphous disembodiments of aesthetic experience.”

Perhaps, unlike some opinions expressed on Winemag recently, it is better to hold onto those special bottles when there is more than one glass to pour into. Let’s share and drink ‘embodied’.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

Foliage in Franschhoek is one of South Africa’s top fine dining restaurants. But today the floor at Foliage is cleared of seats. In their place are crates of raw food and sacks of vegetables. Behind the pass, the restaurant’s award-winning chef-proprietor Chris Erasmus is not tweezing microherbs onto a plate or polishing the rim of a dessert plate. Instead, Erasmus and his team are wearing masks, chopping vegetables.

Down the road in Franschhoek, restaurant industry giant Liam Tomlin is doing the same, working out of his fine dining restaurant, Chefs Warehouse at Maison. Fellow legend Margot Janse, former chef at Le Quartier Francais, is masked up and working too.

For a month, Erasmus, Tomlin, Janse and their teams have been providing soup, stews and porridge – along with dry packs of food – for hundreds of people in Franschhoek. These new “community kitchens” are on track to produce 2 000 meals a day.

In Franschhoek and elsewhere in the country the hard work of feeding the elderly, the jobless, hungry children and the homeless was started without expectation of support. Fine dining chef Bertus Basson has been running a community kitchen from one of his restaurants, Eike, in Stellenbosch. Chef Pete Goffe-Wood has been pitching in to help Wynand du Plessis, owner of catering company Extreme Kwizeen, which has been turning about 1000kg of raw vegetables into soup every week since lockdown started.

Now, thanks to Eat Out’s Restaurant Relief Fund, hundreds more chefs and cooks across the country will be able to follow suit, keeping their restaurants open and their staff employed, while feeding thousands of people left hungry because of Covid-19.

Since the launch of the fund ten days ago, repurposed restaurants that applied for help have received a total of R770 000 in support. This money goes towards petrol, cooking gas, rent and staff salaries.

Aileen Lamb is the Managing Director of New Media, the company that owns Eat Out. She says the purpose of the fund is to mobilize the industry. Since the start of lockdown, several restaurants have announced permanent closures, and all of SA’s 7000-plus restaurants are under threat. Restaurants operate on very slim margins.

Speaking to SABC last week she said: “We have very skilled cooks and chefs … and empty restaurants. We said, there’s a solution here.”

The fund’s top priority is to mobilize the industry; to “get the restaurants up and running again”.

Janse, it would seem, is central to the solution. She and Erasmus started cooking for the local community just days after lockdown was declared. They set an example, Janse is also head of the judging panel for Eat Out’s annual restaurant awards.

Recently, Janse said that the thought of having no food, no money and no prospects for earning got her up in the morning. It also kept her awake at night.

“Margot was a large part of our inspiration to do this,” Lamb said.

The fund’s first big donations were R500 000 from New Media, R100 000 from Retail Capital and R100 000 from Steenberg Vineyards and Graham Beck. Each “community kitchen” that qualifies for support receives between R20 000 and R50 000.

The Restaurant Relief Fund has partnered with Community Chest, Western Cape, and is using its distribution networks to reach those in need. Community Chest is also assisting restaurants to get the necessary permits.

In a short video by Eat Out, many of SA’s top chefs commit to helping the fund. Industry leaders like James Gaag, Luke Dale-Roberts, Chantel Dartnall, Peter Templehoff, Jan Hendrik van der Westhuizen, Vusi Ndlovu and Ivor Jones repeat the words: “I can help”.

Some fine-dining chefs have been working outside their restaurant kitchens. Liesl Odendaal and Arno Janse van Rensburg of Janse & Co have been running the soup kitchen at Ladles of Love. The kitchen makes 2000 meals a day. Kobus van der Merwe of Wolfgat joined a food drive for the needy in Paternoster a month ago.

In another video posted on the Eat Out website, David Schneider of Chefs Warehouse at Maison says: “In a time where it feels like all change is bad … some change is extraordinary and in the darkest of times can cause growth and new opportunities.”

To donate to The Restaurant Relief Fund, click here.

For more on projects related to providing food security during the Coronavirus crisis, click here.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

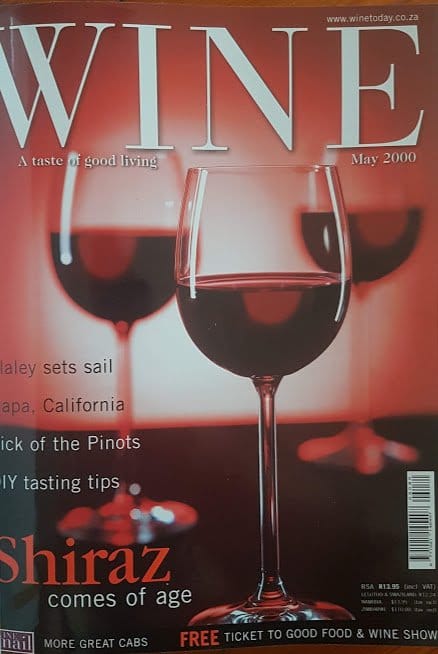

Some insight into SA wine’s recent history – this from the May 2000 issue of Wine Magazine:

Some insight into SA wine’s recent history – this from the May 2000 issue of Wine Magazine:

An update referred to concerns on the part of then Rustenberg winemaker Adi Badenhorst about smoke taint in the wines of the 2000 vintage after a fire had ravaged Simonsberg-Stellenbosch vineyards in January. Other winemakers were apparently sceptical but Badenhorst referenced the occurrence of wines with a smoky character following fires in Hunter Valley, Australia a few years earlier.

The late Tony Mossop released his second vintage of Axe Hill Cape Vintage Port from his farm on the outskirts of Calitzdorp, this being the 1998 selling for around R60 a bottle.

Bruwer Raats, who had joined Stellenbosch property Delaire in time for the 1997 harvest, released a flagship Merlot from that year selling for R105 a bottle, then considered to particularly pricey!

In a report entitled “Cape Shiraz comes of age”, panel member Michael Fridjhon wrote, “Clearly most of the top wines come from a new generation of winemakers, people whose grasp of the varietal is as recent as the new-clone plantings”.

Four and a Half Stars

Slaley 1998 – price: R45

Graham Beck The Ridge 1998 – price: R51

Boschendal 1997 – price: R53,69

De Trafford 1998 – price: R85

Four Stars

Vergenoegd 1997 – price: R36.50

Kanu Limited Release 1998 – price: R40

Lievland 1998 – price: R60

Gilga 1998: R70

Boekenhoutskloof Syrah 1997 – price: R75

Spice Route Flagship Syrah 1998 – price: R75

Simonsig Merindol Syrah 1997 – price: R109

Panel: Tony Mossop (chair), Michael Fridjhon, Allan Mullins, Clive Torr and Colin Frith

Commenting on a tasting that saw no wines breach the 4 Star threshold, Dave Johnson, panel member and founder of Newton Johnson Vineyards four years earlier, commented “The newer clones, replacing the BK5 stalwart, have made for better ripening, better colour and more complex flavours. The reasons why there is not an even more noticeable quality leap are all the usual ones – incorrect sites, wrong choice of oake, yields too high…”

Best wine overall out of 24 tasted was Whalehaven 1998 with a rating of Three and a Half Stars (price: R58 a bottle).

Panel: Tony Mossop (chair), Dave Johnson, Allan Mullins, Clive Torr, Irina von Holdt

David Clarke of the agency Ex Animo Wine Co. provides a podcast consisting of a series of interviews with industry figures, a recent subject being Richard Kelley MW of UK wine importers Dreyfus Ashby. Listen to it here.

David Clarke of the agency Ex Animo Wine Co. provides a podcast consisting of a series of interviews with industry figures, a recent subject being Richard Kelley MW of UK wine importers Dreyfus Ashby. Listen to it here.