Michael Fridjhon: Import prospects

By Michael Fridjhon, 28 October 2015

The recent precipitate plummet of the Rand is arguably just another steeper-than-usual plunge in a trajectory which began in the early 1980s, and gained real momentum after the “Rubicon” speech in June 1985. Those who still have price-tagged bottles of imported wines dating from before this era of currency instability enjoy an excursion into unreality every time they look at what these collectibles used to cost: Romanee-Conti was less than R20 per bottle, Lafite about R15 and Chateau d’Yquem R12. While the hard currency prices of trophy wines have also increased dramatically, the compound effect of a currency which has gone from $1.40 to the Rand to R14 to the Dollar in 35 years has turned the purchase of international icons into a game for the mega-rich.

The recent precipitate plummet of the Rand is arguably just another steeper-than-usual plunge in a trajectory which began in the early 1980s, and gained real momentum after the “Rubicon” speech in June 1985. Those who still have price-tagged bottles of imported wines dating from before this era of currency instability enjoy an excursion into unreality every time they look at what these collectibles used to cost: Romanee-Conti was less than R20 per bottle, Lafite about R15 and Chateau d’Yquem R12. While the hard currency prices of trophy wines have also increased dramatically, the compound effect of a currency which has gone from $1.40 to the Rand to R14 to the Dollar in 35 years has turned the purchase of international icons into a game for the mega-rich.

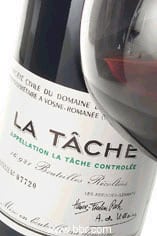

In the same period of time, Cape wine has changed. Once the occasional indulgence of the parochial and the patriot, it is now firmly fixed on the international pantheon: sommeliers in London, Paris, New York and Hong Kong follow the releases of the country’s new wave producers with the kind of interest which, a decade ago, would have been reserved for Antinori’s Super-Tuscans and Alvaro Palacios’s Priorats. We’re not yet up there with Lafleur and La Tache, but we’ve moved a meaningful distance up the vinous food chain. Inevitably – as the Rand plumbs new depths and our best wines scale new heights – the question is asked: is there still a place for imported wines in our domestic market? It’s not an unrealistic consideration – notwithstanding the congestion of Sandton’s roads with Aston Martins and Porsche Cayennes and the recent opening of shopping precincts like the city’s Diamond Walk with its temples of Prada and Armani. At exactly what point do the punters turn around and say “this simply doesn’t make sense.”

Given my lifelong interest in the imported wine scene, I’m not the most impartial voice when it comes to this debate. I’ve lived through the full spectrum of this transformation, having started my wine buying career when South Africa was the world’s most important destination for Bouchard’s Montrachet. When I was a university student in the 1970s, I had a part-time job as the imported wine buyer for South Africa’s largest luxury wine outlet. By about the time I turned 21 I had brought the first stocks of Chateau Petrus into South Africa and within a few years of that I was trading pallet-loads of Chambertin and Corton Charlemagne.

So do I think that imported wines are dead in the water – either because the Rand has put paid to their prospects, or because the Cape wine scene can meet all the needs of the nation’s fine wine drinkers? The short answer is “no.” I don’t see volumes declining significantly, not as long as the Rand doesn’t slip by more than 15% per year. In the past ten years – during which time our currency has halved in value against the dollar – the imported wine market has grown dramatically. The choice of fine Burgundies (indisputably the most expensive segment of the trade) has increased significantly over the period. You can buy literally hundreds more arcane collectibles now than you could at the turn of the century. High-priced cuvées from Piedmont, Northern Rhone trophy wines, prestige labels from Champagne – the super-wealthy have more to select from today than the clients for whom I was shopping in the mid-1970s.

There are also thousands of cases of inexpensive imports entering the local market. Some – like Checkers’ Wines of the World selection – serve to broaden taste expectations (and therefore the consumer base) for everyone. There’s more chance that a R100 bottle of Argentinian Malbec or Romanian Pinot Noir will create a class of adventurous wine buyers than this trade will undermine the local industry. The 10% or so that these wines will increase in price annually as the Rand continues to fall won’t suddenly make them unaffordable. And the 30% or more that top end imports might rise in price (if the Chinese or Russian oligarchs come back into this market) won’t bother those who have a Lamborghini or two in the garage of their homes in Camps Bay.

So what about our new rock star winemakers – won’t they profit at all from their own success and the decline of the Rand? The answer, of course, is “yes.” They already sell every bottle they produce, much of it locally, but increasingly also abroad. They will price their products upwards as the tolerance for excess increases and the desire of well-heeled consumers for the unobtainable enhances their brand stature.

I can’t see any of this being bad – except perhaps in the puritanical sense of the word. If we want the top end of industry to grow, we need to cultivate the cult wine segment, we need to reward craft and we need to raise the price ceiling with demand-driven strategies, rather than with marketing thumbsuck. In this the imported wine market and the falling Rand are passive allies: just by being there, they change the game.

- Michael Fridjhon has over thirty-five years’ experience in the liquor industry. He is founder of Winewizard.co.za and holds various positions including: Visiting Professor of Wine Business at the University of Cape Town; founder and director of WineX – the largest consumer wine show in the Southern Hemisphere and chairman of The Old Mutual Trophy Wine Show.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.