SA Wine History: Fighting for Vergelegen, then and now

By Joanne Gibson, 9 April 2019

As the editor wrote last week, Vergelegen seems set for great things again, now that virus-free vines are reaching full maturity following an extensive replanting programme implemented in the early 2000s.

‘I basically put my winemaking life on hold for 10 to 15 years because I could not work with anything except young vines,’ says André van Rensburg, winemaker at the magnificent 3,000-hectare Helderberg property since 1997. Adamant that at least 10 of the best vintages of his career still lie ahead of him, his biggest worry is that Anglo American, which owns Vergelegen, might insist that he take mandatory retirement at 60 – in a mere three years’ time.

Joking about reincarnation, if that’s what it takes to see his beloved Vergelegen realise its full potential, Van Rensburg makes it clear that he won’t be put out to pasture without a fight – and it won’t be the first time that someone has fought to tend the vines a little longer at Vergelegen.

In 1706, a group of vrijburghers led by Adam Tas and Henning Huysing drew up a petition accusing the Dutch East India Company’s governor at the Cape, Willem Adriaan van der Stel, of corruption, nepotism and generally being a ‘very impious, tyrannical, and rapacious leader’. In particular, he was accused of using Company resources to develop his private country estate.

This was Vergelegen, which had been granted to him by Commissioner Wouter Valckenier in 1700, and which the petitioners now alleged was ‘large beyond measure, and of such broad dimensions as if it were a whole town’.

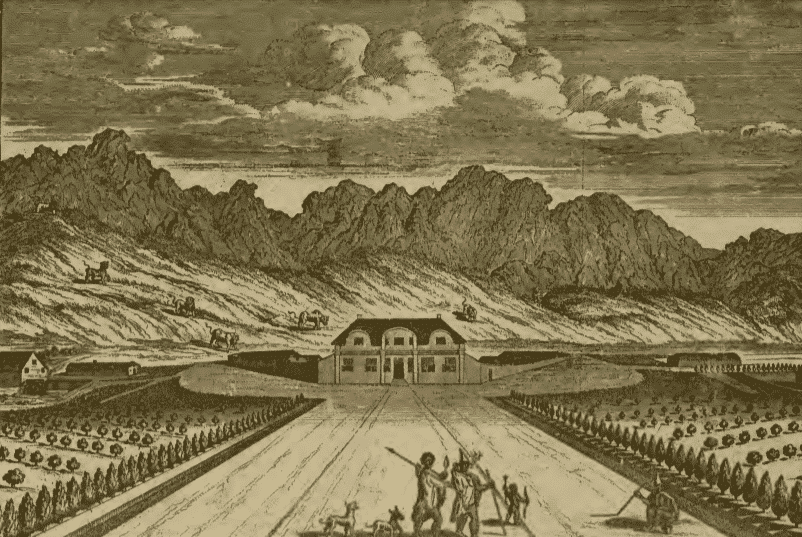

In his Defence, Willem Adriaan van der Stel provided this ‘true drawing’ of Vergelegen to show that his homestead was ‘merely a house with one storey’ that could surely ‘not be considered too large for harbouring his large family’. He insisted that the only other structures on the farm were a labourer’s cottage, a stable, a wine press and slave quarters, ‘the rest consisting of cornlands, vines, plantations, and wilderness’ (note the wild animals and tribesmen, ready to attack).

Van der Stel’s response was a ‘short’ 1,098-point Deductie (Defence), which refuted all of the claims made against him (complete with sworn declarations in which many of the petitioners retracted their accusations, admittedly after being ‘judicially interrogated’). And it included the following references to winegrowing:

‘Regarding the vines, [Van der Stel] is bound to say truthfully and regretfully that with great expense and trouble he imported all kinds of vine stocks into the Cape; that he planted about 200,000 of the same, two-thirds of which grew; that he had good reasons to hope to enjoy some fruit of the same in course of time – an impossibility during the first years; [and] that to his great loss, and without his fault, he has now been so pitifully deprived of the same.’

Perhaps André van Rensburg can use the bit about being ‘pitifully deprived’ when he argues to stay on, albeit as winemaker and Anglo employee rather than owner and Company official…

And let’s hope he has more success than Van der Stel who on 17 April 1707 received news that the Company’s directors, the Lords XVII, had officially dismissed him as Cape governor, ordering him to hand over Vergelegen and return to the Netherlands.

Needless to say, Van der Stel refused to leave Vergelegen quietly, requesting a delay until a reply to his Defence had been received. In June the Cape’s Council of Policy agreed that the sale of Vergelegen should be postponed until the arrival of his replacement as governor, Louis van Assenburg, especially as it was the beginning of the rainy season. However, Van der Stel was reminded that he should be ‘pleased to submit to the orders of the Directors, who had disapproved of the grant of the piece of land, and wished that it should be restored to the Company with the whole plantation on it, and that he should accordingly take care to leave everything in the state in which it is at present’.

The matter dragged on until December, with Van der Stel complaining about the harsh proceedings against him, and protesting that he could not simply ‘leave’ things given that the lands had been ploughed and sown with grain before he had known of his dismissal, and the harvest was now at hand. He added that he was drawing no pay or rations from the Company, yet still had to maintain a large number of slaves and servants, and therefore ‘thought it but fair to sow some corn for them’. Not allowing him to gather the harvest freely ‘would be like taking the bread out of his mouth’.

On Christmas Eve 1707, the Council decided to notify to Van der Stel ‘in proper and civil terms…to evacuate the homestead and lands for the Company before the end of January’. He again asserted his right to the crops currently being harvested, and ‘with deep respect’ requested that his removal from Vergelegen be delayed until the end of February 1708, in the hope that a favourable response to his request for mitigation might still arrive from the Lords XVII.

By 17 February 1708, when Van der Stel was once again ‘civilly’ reminded to vacate Vergelegen, Louis van Assenburg had finally arrived to take the reins as governor. But it was now almost time for the grape harvest, so to spare the Company the ‘great trouble and inconvenience’ of pressing grapes at a farm located so far away, Van Assenburg proposed that Van der Stel be asked to have the grapes pressed by his own men, using his own materials and his own casks, with two of the Council’s deputies present. If mitigation did not arrive, either his wines would become the property of the Company, and he would be paid for his trouble and expenses, or he would ‘surrender’ to the Company some of his wine ‘at a price agreed upon’.

Needless to say, Van der Stel agreed to the second option, negotiating to sell half (rather than two-thirds or three-fifths) of his production to the Company, and promising to carefully note down both the quantities and sorts of wines, e.g. white muscatel, red muscatel, ‘steen’ and ‘groen’ grape.

This might seem a surprisingly generous deal for the disgraced former governor, but the Council recorded: ‘His wines were of a particularly good sort and flavour, and would not be unwelcome to the Company, as they could be sent to Batavia and Ceylon, where they would undoubtedly find a good market.’

So there we have it: the first record of Vergelegen’s wines – albeit from very young vines – being ‘particularly good’.

Once he’d met his final obligations, Van der Stel departed from the Cape on 23 April 1708. What he left behind at Vergelegen was not an estate the size of a whole town (in fact the original grant was for 400 morgen, less than half the size of his father’s farm, Constantia) or even a particularly ostentatious homestead (‘the house of Henning Huysing, the chief mover among the subscribers, was in all respects much larger, higher and grander,’ wrote Van der Stel, referring to Meerlust).

But he started something remarkable at Vergelegen with its homestead, tannery, workshop and wine press; its grain fields, stores and water mill; its vineyards, orchards and orange groves; and its now ancient camphor and oak trees (including one believed to be South Africa’s oldest living oak).

What happened to Vergelegen in the years after his departure is also interesting – but that’s a story for another time.

Bibliography

Leibbrandt, HCV: Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope (Journal, 1699-1732; Letters despatched, 1696-1708; The Defence of Willem Adriaan van der Stel); originally published by W.A. Richards & Sons, 1896-1905, digitised by University of California Libraries (https://archive.org)

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.