SA wine history: The freed slaves who owned land in Stellenbosch’s Jonkershoek Valley

By Joanne Gibson, 8 October 2019

6

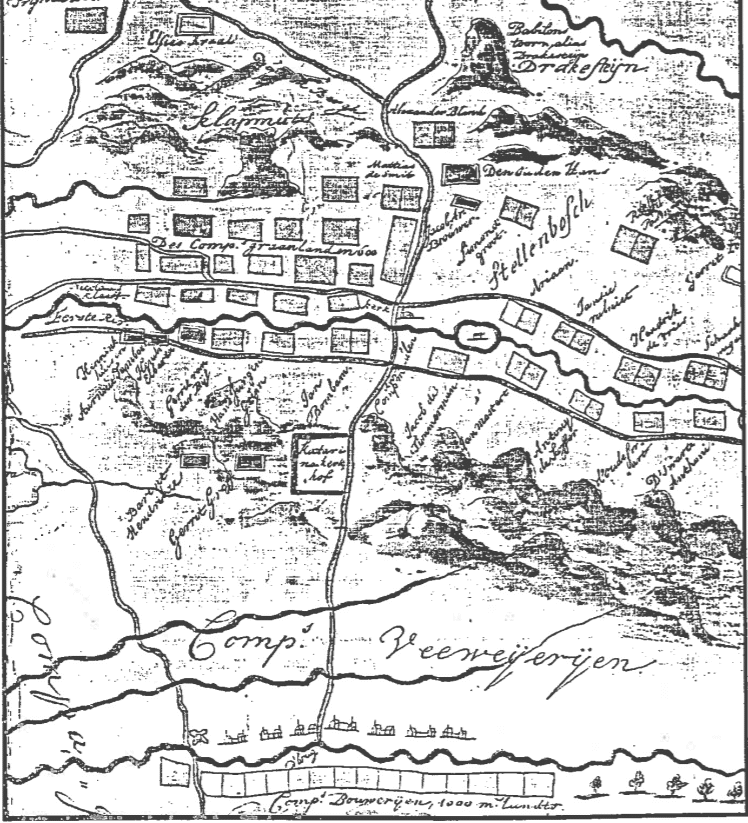

On a circa 1688-1690 map that shows the oldest Stellenbosch farms in the names of their first owners, including Roelof Pasman of Rustenberg and Gerrit ‘Grof’ Visser of Blaauwklippen, it’s hard to miss two tracts of land clearly marked as belonging to ‘Antony de Kaffer’ and ‘d’Swarte Anthonie’.

from the Cape Town Archives Repository, Ref: M1/273

In fact Anthony van Angola was one of five so-called Free Blacks (manumitted slaves) who were given land in the Jonkershoek Valley in the early 1680s, with formal grants following in 1692. He and a fellow countryman, Manuel, were given ‘sekere stukken lands’ amounting to almost 58 morgen and collectively known as Angola. A little further east along the Eerste River, Louis van Bengalen was given 29 morgen of land, known in due course as Leef-op-Hoop, while Marquart and Jan ‘Luij’ van Ceylon were granted 25 morgen further upstream, later known as Oude Nektar.

The most remote farm in the valley belonged to Jan Andriessen, originally from Konigsberg in Prussia, whose nickname was Jan de Jonker (hence the name of his farm and, in due course, the entire valley). His wife, Lijsbeth Jansz, had also been born into slavery at the Cape. The farm at the entrance to the valley belonged to Isaaq Schrijver, a Dutch East India Company official who named it Schoongezicht and soon enlarged it through the acquisition of Jan Mostert’s farm, Mostertsdrift.

Regarding the Free Blacks, Manuel van Angola disappeared from the records quite quickly, as did Marquart van Ceylon who on 13 September 1690 stated that due to his advanced age and inability to cultivate his property properly, he was handing it over to Jan de Jonker in exchange for which he would receive food and shelter for the rest of his life. Louis van Bengal, too, abandoned his Jonkershoek farm in 1690 to return to Table Valley where he had owned two erven since the 1670s (one situated where Gardens Shopping Centre is today, the other in Hout Street). This followed a scandal involving his ‘wife’, Lysbeth Sanders…

In short, Lysbeth was a Cape-born slave who in 1678 had broken into Louis’s home and stolen a gold ring and two silver buttons, in compensation for which she was ceded to him. He freed her on 27 July 1683 – the date of their second daughter’s baptism – but in 1688 he sued her for being ‘absent’, whereupon she told the court that she had not fulfilled her pledge to marry him as the condition had been that he should desist from abusing her ‘met smijten, slaan en dreijgementen van dooden’ (by throwing things at her, hitting her and threatening her with death). A few months later, Louis accused Lysbeth of having an affair with his knecht (farm overseer), a 56-year-old Englishman named William Teerling, and on 6 April 1689 she confessed to being pregnant with Teerling’s child.

Teerling was fired and Louis then asked the court not only to release him from his promise to marry Lysbeth but also to reinstate her as a slave (something he would continue to press for – vengefully but unsuccessfully – until his death in 1716). Despite all the acrimony, he seems to have been respected in the community as a confirmed member of the Dutch Reformed Church, and his three daughters with Lysbeth were absorbed into ‘respectable’ society, becoming the ancestors of Afrikaner families including Coetzee, Du Plessis, Myburgh, Pretorius, etc.

The two most successful Jonkershoek pioneers were Anthony van Angola and Jan van Ceylon. By 1688, Anthony owned two slaves, two horses, 18 cattle and 196 sheep, and he had planted fields of corn and rye as well as 600 vines – a number that had increased to 4,000 vines by 1692. It seems that he employed William Teerling after his dismissal by Louis van Bengal, with two other white men also said to have worked for him (Hans Jes from Sleewijck and Christian Marenz from Hamburg). Unfortunately he died in 1696, probably only in his mid-40s, and one can’t help wondering what he might have achieved had he lived longer.

As for Jan van Ceylon, we’ve met him before: it was his children who rescued Abraham Bastiaansz Pijl (first owner of Alto) from drowning in the Eerste River in 1703, and his house in which Pijl eventually succeeded in committing suicide by slitting his own throat. Following Jan de Jonker’s death in 1698, Jan van Ceylon had purchased Jonkershoek for f400, selling it for f800 in 1701 (minus three morgen that he kept for himself).

I suppose the period of Free Black land ownership in the Jonkershoek Valley was relatively short-lived, but the fact that it happened at all is significant, with a number of historians concluding in recent years that racial patterns of land ownership and settlement were more fluid during the late 1600s than previously recognised. ‘The extent to which free-blacks were accepted into social and economic life during the first decades at the Cape is surprising,’ wrote Hans Heese, agreeing with Anna Böeseken’s earlier conclusion that freed slaves at the Cape were not treated as a separate group from the free burghers.

Only in the 1707 petition signed by Adam Tas and 14 others against governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel – owner of Vergelegen and himself the great-grandson of a ‘black’ woman – was racism first (overtly) expressed regarding ‘the Caffers, mulattos, mestizos, castizos and all that black brood living amongst us, and related to European and African Christians by marriages and other connections, who have to our utter amazement increased in property, number and pride…’

Nonetheless, even if all (free/Christian) men were equal in the late 1600s, some were still more equal than others. Slowly but surely, Isaaq Schrijver (and later his widow, Anna Hoecks) bought up virtually the entire Jonkershoek Valley – Anthony van Angola and Louis van Bengal’s farms in 1696, Jan van Ceylon’s Oude Nektar in 1712, and Jonkershoek in 1714.

If Schrijver had 4,000 vines planted in 1700, his widow had increased plantings to 10,000 vines by 1709, and to 15,000 vines by 1712.

So far I haven’t been able to establish when or under what circumstances Anna Hoecks arrived at the Cape, but she had two sons from a previous marriage, namely Jacobus and Gaspar Hasselaar. She and Jacobus Hasselaar died sometime before 12 August 1723, which is when her daughter-in-law, Maria Elizabeth van Coningshoven, took the inventory of their combined estates – and acquired the much-enlarged Schoongezicht with its 150 cattle, 400 sheep and 20,000 vines.

And who was Maria Elizabeth van Coningshoven? Rather satisfyingly, she too was the daughter of a woman born in bondage, namely Jannetje Bort van de Caep, who was manumitted on 8 May 1686 and married Dirk van Coningshoven on 22 December 1686.

Maria Elizabeth never remarried, and when she died in 1755, Schoongezicht became the property of her daughter, Anna Hasselaar, whose husband Christoffel Groenewald had died in 1748. Anna also didn’t remarry, and Schoongezicht would remain (albeit once again sub-divided) in the hands of her sons, Christoffel and Johannes Casparus Groenewald, and grandson, Coenraad Johannes Albertyn, well into the 19th century.

Today, of course, we know Schoongezicht as Lanzerac, and Oude Nektar as the home of Stark-Condé Wines, with Rudera Wines in between, and with Neil Ellis and Etienne le Riche having also helped put the Jonkershoek Valley on the quality map in recent decades. Not to mention the Klein Gustrouw wines that were, for a few years, produced by PSG founder Jannie Mouton and Steinhoff CEO Markus Jooste on their neighbouring farms, which once belonged to Anthony van Angola and Louis van Bengal…

How will the next chapter unfold, I wonder?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Böeseken, Anna: Slaves and Free Blacks at the Cape, 1658–1700, Tafelberg, Cape Town, 1977

Heese, Hans: Groep Sonder Grense, Die Role en Status van die Gemengde Bevolking aan die Kaap, 1652-1795 (2nd edition, Protea, Cape Town, 2005), translated by Robertson, Delia for the First Fifty Years Project, 2015

Pistorius, Penny & Harris, Stewart: Heritage Survey: Stellenbosch Rural Areas: Jonkershoek

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Stellenbosch Heritage Foundation | 15 July 2020

Dear Joanne

Thank you for an insightful article. We would like to publish this article on our website http://www.stellenboschheritage.co.za

Please let me know if you have any objections against it? We will credit both you and WineMag.

Regards

Stellenbosch Heritage Foundation

Christian Eedes | 15 July 2020

Hi Stellenbosch Heritage Foundation, Speaking on behalf of Joanne, you are most welcome to re-publish the article.

ELVIRA VAN OUDTSHOORN | 15 October 2019

Great stuff, Joanne. There can never be enough research done and published around our earliest histories. All the best

Charles W | 15 October 2019

Another very good read on the more recent history of Stellenbosch is by Herman Giliomee – “Always been here” – The story of a Stellenbosch Community. This relates as to what a significant impact the “coloured community”had on Stellenbosch and the effect of the forced removals program of the 60s. A very moving story and without this the integrity of this resilient community Stellenbosch would be half the place it is today.

Russell | 10 October 2019

Very informative and thought provoking.

Guy | 9 October 2019

An interesting read. Thanks.