Tim James: Establishing a firmly terroir-based ward system in South Africa

By Tim James, 21 August 2023

3

I’ve been having further thoughts about the whole question of wards since my article on the subject last week. Second thoughts, corrective thoughts, in fact – and largely pushed in that direction by winegrower Eben Sadie, who felt himself to be “collateral damage” of my piece. As a launchpad for a defence of wards, I quoted Eben’s significant general doubts about their value in South Africa at present, as mentioned by him at a tasting of his wines recently. Indeed I was wrong to do so without checking with him and putting the doubts in a larger context of his thinking on the subject, and apologise for that.

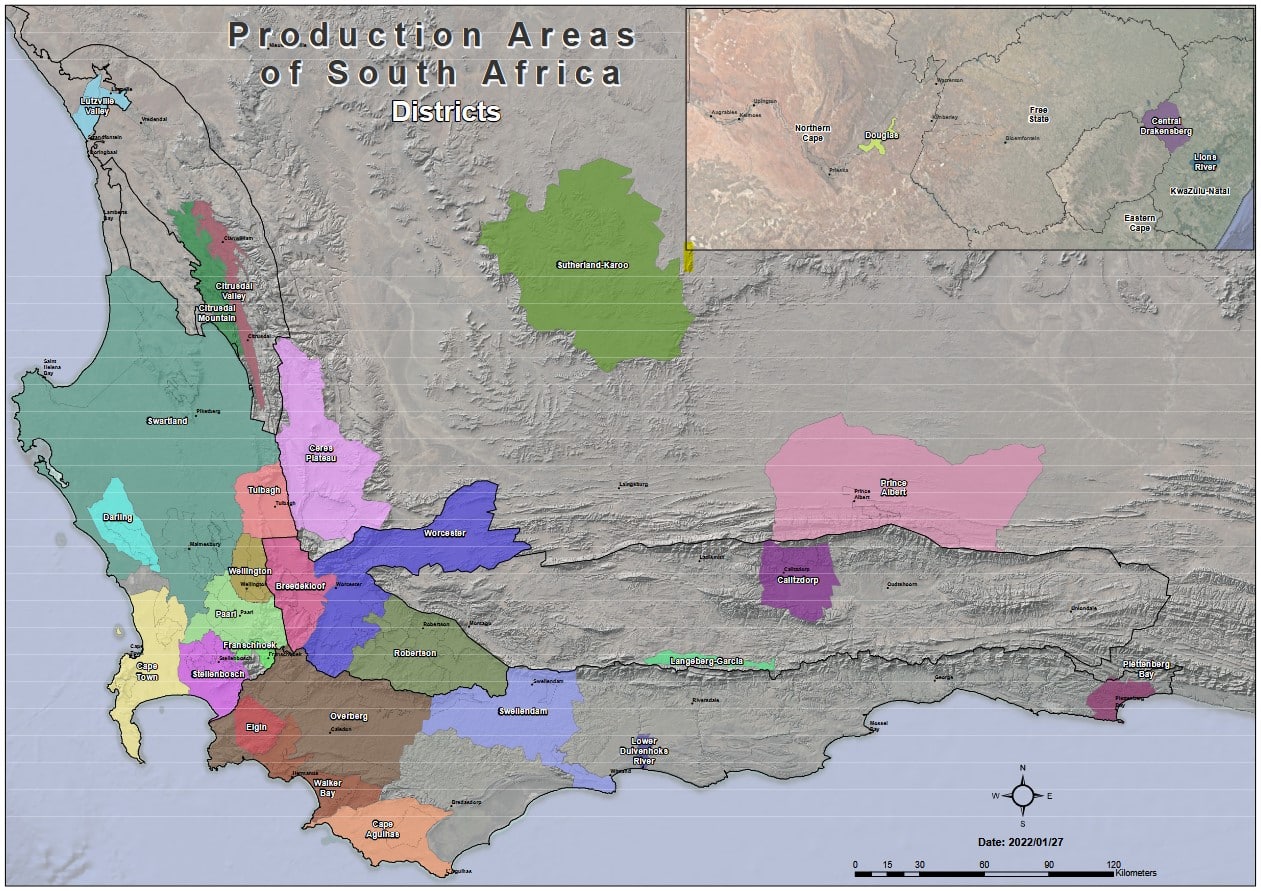

The reason the topic of wards came up at all on that occasion was that Eben was justifying his preference for using districts within the official Wine of Origin to indicate the source of his wines. I mentioned last week some of his problems with wards, but basically (and he justifies this at length), he thinks that a genuinely terroir-based appellation system should take much more time and wine-growing experience to emerge (in conjunction with rigorous science-based metrics of all aspects of soil, slope and meso-climate) than is happening here. Stellenbosch, he suggests, is one district which can more plausibly develop wards, because grapes have been widely grown and vinified there for a decent length of time.

Districts in the WO system, on the other hand, avoid invoking the real questions of terroir and are based on broader geographical and climate considerations – in conjuction, often enough, with such things as political boundaries. Incidentally, I incorrectly said that Sadie Family Wines avoided using the district names for Skurfberg and Kokerboom, basing that statement on the latest images of labels shown on the technical details sheets on their website. In fact the bottle images shown were composites, with new vintage dates simply applied to older bottle photographs; for a few years now those two wines – and Soldaat, which used to carry the ward name Piekenierskloof – have claimed the district name, Citrusdal Mountain.

Further discussion and investigation has persuaded me that I was naïve in accepting that the drawing up of ward boundaries is beyond reproach. I’d need to do further research to offer details confidently, but I accept the general point that, in terms of offering anything like a definitive terroir-based system, at least many of the wards are problematical.

The greatest models of a genuinely detailed system of terroir for wine are in classic Europe: parts of France (most famously and scrupulously in Burgundy), Germany, and also in other parts, especially in areas of Portugal, Spain, and Italy. Such long-established and close discrimination holds the wider fine-wine world spellbound and envious. If South Africa was probably the first of the “New World” countries to set out on building a serious appellation system, the other major producer areas are also busily at it. California is one of the most assiduous. There are, at the latest count I could find, 139 American Viticultural areas or AVAs there, some of them as small as a few dozen hectares. Napa Valley AVA, which is analogous to a South African district like Stellenbosch (it was designated nearly a decade later) has 16 smaller AVAs nested within it. These are analogous to wards, I suppose, though I know little about the way they are established.

The problem with doing things in rather more of a rush than the hundreds of leisurely years spent by monks, princes and bishops in making fine discriminations in Burgundy and the Rheingau is that mistakes are going to be made, sometimes serious ones, of omission and commission. And then, as Eben points out, you’re stuck with them for ever (and that inevitably affects future terroir plottings). But one thing is certain: everywhere around the ambitious wine-growing world, it will be done more or less in a rush. Of course it can still be done in a better or a worse fashion. But half a millennium in a rural, pre-capitalist, pre-information-hungry world is not available.

One producer response is to ignore a problem-riddled system of wards (to call them all that, for convenience). It is a responsible position, and replete with integrity – and certainly, as is the case with the Sadie Ouwingerdreeks, which is mostly de-facto based on single vineyards, there can be every attempt to work in a terroir-conscious fashion. Another is to accept the problems as given and inevitable (and forget about cementing a system which one day is going to fully reveal its inadequacies). I argued last week that in South Africa the ward system has prompted many producers to explore terroir. Perhaps most of them would have done so without the ward system anyway. But serious wine-drinkers are also prompted by wards to consider terroir, as they are by single-vineyard wines and, albeit often to a lesser extent, by estate wines. If the ward system is flawed, there are inevitable problems here, admittedly.

It’s not (for me) an easy question to grapple with. But there is a case – fortunately or unfortunately – to be made that there is one fine-wine factor which tends to trump terroir, even in the heartland of terroir-based appellations: the producer. In 2017 on this website I reported on a horizontal tasting of the red wines made by the five landholders in the famous Burgundy vineyard Clos St-Jacques, where the five have essentially, potentially identical strips of the 6.7 hectare vineyard. The five wines showed, I said, “clear differences as well as some similarities, predominantly structural”. There was “no question that the viticultural and winemaking skills and sensitivities of the different domaines trumped the terroir at least in what must be the most important matter: ultimate wine quality”. That difference is such as to translate, year after year, into consistently very different prices achieved on the international market for the wines. That’s subject to change again, of course.

It would not be hard to show that sort of result elsewhere in the great classic appellations. Serious wine-lovers are nearly all united in respecting terroir – but only up to a point. Disconcerting as it is to decide that frequently the viticulturist and winemaker can be more important (but personnel changes; terroir persists), it does offer a bit of comfort while floundering in the debate over wards.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. He is a taster (and associate editor) for Platter’s. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

PK | 24 August 2023

Tim thank you for another relevant and well timed piece of writing and to kind of comment on both pieces and touch on some comments Colyn left on the other article. It is an interesting one the, should we call it appellation/denomination system that we have in South Africa. But as so many things in our beautiful country, it seems as though the original idea was a great one, but then when it was put into practice and someone was tasked to map it out and put it together, it was delegated to the office intern or old mate that doesn’t work in the wine department… ‘you had one job’! Hah

Looking at the bare bones there is potential, but it seems to fit more easily and work more easily for some districts than others, as geographically some districts can lend it self to being broken up into distinctively different wards more so than others. Stellenbosch for example and even to use the example of the Hemel-en-Aarde, which was at first very controversial and till today still divides that little valley massively with the 3 wards known as ‘the gate keepers, the people on the hill and the other lot at the back of the valley’… but that’s down to wine industry politics and it has actually done a huge job for the valley, even if it will only be realised fully after the pioneers are long gone.

I think commerciality also comes into play with the districts and wards, as Colyn mentioned more than 90%+ of consumers are not familiar with anything beyond a districts name on the bottle and even then it is a push, but it’s the more top end dare we say 5% to whom it makes a big difference and knowing that South Africa is a far more intricate place, with a beautiful mosaic of regions, sub-regions, estates and single sites that should be identifiable by a single name. As South Africans, as people and as a country, we are a rainbow nation with a complex and colourful history and beautifully bright future, BUT I do find we always want to dumb things down to be understood but other people that don’t quite understand out story and where we are from and this also goes for wine. We are almost apologetic about having to explain a story and having to explain to people that we also make wines outside of Stellenbosch, but I feel we should celebrate that and educate and tell people who want to know. Yes it may not be everyones cup of tea, well then South African wine and/or district names will do the job for them, but for those 5% or less, let’s celebrate our complexity and explain to them that Stellenbosch and Hemel-en-Aarde is far more complex than they think, Sondagskloof is a place, there’s some crazy people making wine in Agulhas and Breedekloof has 14 wards… or maybe bad example 🙂

It is the system we have and yes we may have to explain it a little, but it is what it is and let’s work with it, rather than break it down, because it doesn’t quite work for me as a producer or for what I am trying to do within my brand.

Jen | 21 August 2023

What’s interesting to see, is that there are wines from wards within a region that consistently perform well (look at beeslaar, kanonkop, simonsig, beyerskloof…some of their wines that perform well come from the same block) another example would be Flagstone and Benguela cove also winning awards for the same cultivar out of the same block. It would be interesting to prove the point of terroir on a ward or single block level, albeit for the differences in winemaking. On the topic of single vineyard origins, terroir can vary so much within a ward itself, that we can identify different single blocks that are treated identically within the cellar – surely terroir cannot then be limited to a region/district. I like to think of it on a vineyard block level…. As a winemaker, I am very pro the use of wards because I firmly believe that our terroir varies down to a vineyard block level within the ward. One cannot group Philedelphia with Constantia and Durbanville – our wines show some similarities but are vastly different. Much like a Cabernet from the beloved golden triangle in the Helderberg that cannot be compared to Simonsberg cabs. While there are pros of districts, such as recognition of a broader area on a label (Stellenbosch, Cape Town etc..), I cant help but feel a touch more proud to see the wards on the label, especially if its a damn good wine.

GillesP | 21 August 2023

I am completely with you on that comment Jen. What happens in the cellar is very important but we can’t keep having Stellenbosch or Swartland or Hemel en Harde as a district on its own if I understood correctly.