Tim James: Old adventures in South African sherry

By Tim James, 24 February 2025

1

My sherry geekiness of a few weeks back prompted me to think about South African sherry-style wine. Not much else around here is likely to make such a prompting. Since Monis dropped their few examples in 2023 there’s virtually nothing left – apart from a few of the crassest sweet “Old Brown” examples. Klein Amoskuil made an interesting attempt to revive flor-style sherries, but I think (and am open to correction) that a fino-style solera has not been fully developed there over the last decade. Only Adi Badenhorst seems intent on a serious attempt to build the category, at his Saldanha Wine & Spirit Co (in the seaside town which gives its name to the brand). There are numerous wines made with some influence from biological ageing under flor, but they don’t aspire to proper sherry-styling – the orientation is more to the Jura model.

It’s hard, in fact, to realise now just how important South African “sherry” once was. I’ve just been counting their number in Kenneth Maxwell’s 1966 book, Fairest Vineyards, the first attempt to give a comprehensive catalogue of locally available Cape wines (the KWV’s wines, apart from fortifieds, were not allowed to be sold in the country). The wines and brandies are listed according to the styles suggested by the producers. (Maxwell, incidentally, was only a part-time and amateur wino; he was a PR consultant and a leading motoring journalist, of all things.)

Fairest Vineyards lists 54 sherries, as they were unabashedly called then: 18 medium-sweet, 14 sweet, 8 medium dry and just 6 extra dry. Showing that the South African sweet tooth was getting caries even back then, and helping to give sherry the sort of reputation that rosé was (and still is, to an extent) lumbered with. To put the guide’s 54-strong sherry showing in perspective: it’s more than the total of red table wines (38) and of sparkling (40); there were 93 whites.

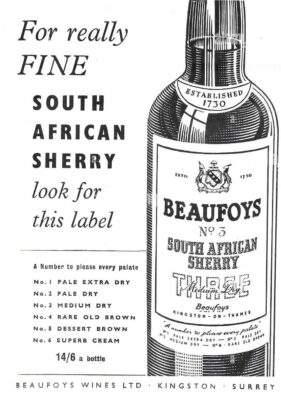

The next year, however, was to see the start of the local sherry-industry collapse – initially the export market to Britian. A London court agreed that the name sherry should be restricted to the original, authentic Spanish product. Somewhat later even “South African Sherry” was not to be allowed, and then, in 2012 by which time it didn’t matter so much any more (though the “port” equivalent did), the EU saw to it that no mention of sherry at all was to be made on labels, even for the home market.

The establishment of the port and sherry industries in South Africa went hand-in-hand with the youthful KWV’s need to find something to do with all the spirits it was distilling from the poor quality wines that it was guaranteeing to buy. In the latter 1920s and ’30s it was Dr Charles Niehaus who did the necessary research into the possibilites of maturing wine under flor in South Africa – starting with some Spanish flor and then finding suitable local strains.

Some facts and myths in the origins of sherry-making in the Cape in the 1930s have been entertainingly and debunkingly written about by Emile Joubert. But he doesn’t go back to the 1890s, which saw the first, utterly bizarre and inevitably doomed attempt to produce sherry here, at Groot Constantia. I’m sure I’ve told this story before, but it’s worth repeating. I found it in the parliamentary records of the time, because Groot Constantia, as a state-owned property was obliged to report to its masters each year. (At the time, the Government Wine Farm was largely engaged in growing rootstock to supply an industry grappling with phylloxera – see here for that story – but under its manager, JP de Waal, was also engaging in some important experimentation and innovation.)

So, the report for 1898 tells of the visit some three years before of one Señor de Castro-Palomino, who “started experiments on this estate and elsewhere with the object of converting our heavier types of white wine into wines partaking of the nature of Sherry”. There was to be no nonsense about special yeasts or soleras, however. The process “consists merely in the addition of a quart bottle of a colourless liquid product with a pungent odour, and known by the name of ‘Mutagina’ to a barrel (108 gallons) of wine, and in thoroughly mixing the wine with this liquid.” Leave it for a few weeks and there you have it – sherry, one hopes. The magical Mutagina was “a concentrated extract of Spanish Sherry, to which a small quantity of antiseptic has been added”.

The experiment, says the 1898 report, has “created a very favourable impression”. Unfortunately, the impression didn’t last into the next year’s report (which included discussion about the debate over whether field-grafting onto rootstock was better than nursery-grafting, and reported that, for various reasons, “the output of the old famous Sweet Constantia will be considerably reduced”). The Mutagina only works, it was reluctantly reported, when applied to fortified wines. Also, they’d clearly done a bit of work on its make-up and found that the preservative in it was formalin (a solution including formaldehyde). Even in those lax days, it was recognised that this was not such a good thing to have in your wine, so the development of a local sherry industry had to wait another 30 years or so.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Emile Louw Joubert | 24 February 2025

Truly insightful, Tim. Re Niehaus: the legend of him nicking some flor from a bodega and ‘smuggling’ it off in a handkerchief is partially true. In Rufus Kenney’s book on Perold, it is told that Niehaus returned to Geisenheim with the flor-holding hankie. However, the fraulein doing housekeeping washed it with borox, killing the flor, much to Niehaus’s chagrin. Apparently he found flor at Vergenoegd, kicking things off for KWV sherry.