Tim James: On SA’s oldest red-wine vineyard

By Christian Eedes, 3 April 2017

1

Around 120 years ago – let’s say in 1900, to fit with the formal record, though that was made later – a vineyard was planted on the outskirts of Wellington, alongside the dirt road down which ox-wagons laboured into town. The first and unanswerable question is – why? These were bad times in the Cape wine industry. General economic recession, little export possibility, and the ravages (since the mid-1880s) of phylloxera made winegrape-farming a mug’s game. And yet, implacably, it continued.

One thing about the vineyard is easier to explain: the grape variety. Cinsaut had been hugely expanding since its arrival in the Cape in the 1880s. Largely because of its high-yield propensity it soon became the dominant black grape, behind only semillon and chenin blanc in terms of overall plantings. Its rapid spread was fostered by cinsaut being used for fortified, sweetish wine favoured by black mineworkers in the Transvaal – before racially-based prohibition put a stop to that (and helped push the Cape wine industry further into depression).

New vineyards were by this time being planted, when possible and affordable, on American rootstocks as the only viable response to the devastations of phylloxera. But here demand exceeded supply. In 1900, fewer than two million grafted vines had been planted in the Cape – out of some 87 million. So this Wellington vineyard was fairly unusual; and interestingly a variety of different rootstocks were used, no doubt testifying to the difficulties of sourcing them, as well as to the experimental uncertainly as to which were the most suitable for different conditions and varieties. As this vineyard starting reaching its present venerable age, neglected, some of the vines died – perhaps those on less suitable rootstocks, I wonder?

But the vineyard lives, revived at great expense and lovingly cared for, the gaps where old vines have died now occupied by thrusting young vines. As far as we know, it’s the oldest red-wine vineyard in the Cape. Peer into the gnarled hearts of these vines and see history.

The road alongside is tarred now, of course, and people thundering past have no idea of the significance of this nondescript patch of vines – though perhaps the more viticulturally alert have noticed its transformation into green vitality in recent years. And that nowadays sheep and cattle no longer graze in it: the vines are now enclosed by a rustic pole-and-wire fence, a quaint African version of the European “clos”!

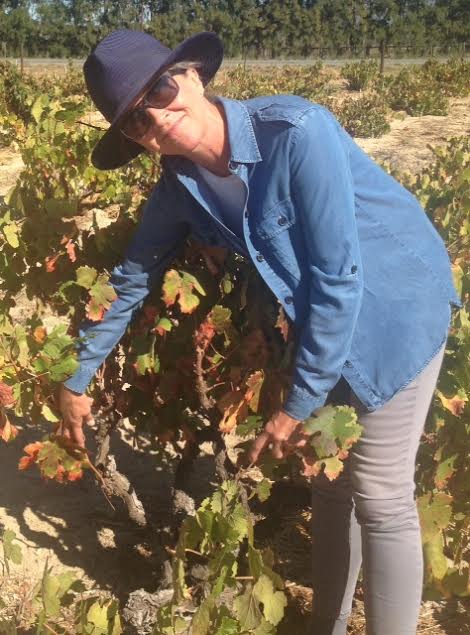

Some knowledgeable passer-by might, perhaps, have noticed the elegant figure of Rosa Kruger among the vines, with the team of workers to whom she gives great credit for their skills and their interest in the vineyard. Or might have seen Chris Mullineux – in this case the Chris Mullineux not of the Swartland but of Leeu Passant, the Franschhoek part of Mullineux and Leeu Family Wines, whose maiden release includes a “Dry Red Wine”, with a cinsaut component off this historic vineyard, which it holds on a medium-term renewable lease.

Rosa says it was Chris (the vital link between vineyards and the cellar where Andrea Mullineux rules), who four years ago insisted on bringing this old vineyard back to life, whatever the cost. “Everything was wrong about it”, says Rosa, who had severe doubts about its viability. It was on sand, in terrible condition; could a deal be struck with the farmer? It could, and a great deal of work later it yields a respectable five tons per hectare.

Last week I tasted the wine (largely destined for Leeu Passant Dry Red) that was made from the 2017 harvest. If your idea of cinsaut is a charming and prettily aromatic light red wine, you would scarcely recognise this deep, serious and rather potent and tannic red wine – it even hints at magnificence!. Andrea’s aim in leaving the wine on its skins for about a month was not to negate the delightful primary fruit, but to bring in spice and other complexities. In fact, she’s experimented with making stand-alone cinsauts from this old vineyard and another block, planted in 1932 in Franschhoek. I hope to see these wines: they will usefully complicate our love affair with those rather trivial, albeit charming and fresh, cinsauts that now proliferate and dominate. How often have I said: the Cape wine revolution rolls on.

- Tim James is founder of Grape.co.za and contributes to various local and international wine publications. He is a taster (and associate editor) for Platter’s. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Alain | 11 April 2017

We tasted a 1971 Oude Libertas Cinsaut from my cellar @ l’Aubergine last month with some French wine journalists.

The wine was amazingly good tending towards an old Pinot Noir. The tasters were floored so was I. It was the best wine of the tasting followed closely by a 1973 Bertrams Shiraz also delicious. We had 95 + Parker French wines in the tasting.

Who say that SA wines do not last?