SA wine history: On Cape wine during the 1660s

By Joanne Gibson, 10 July 2018

6

When the Cape’s first winegrower, Jan van Riebeeck, departed for VOC headquarters in Batavia in April 1662, his successor as commander was Zacharias Wagenaar of Dresden, Saxony (Germany). The son of a judge and painter, Wagenaar was a clerk, merchant, member of the Court of Justice and illustrator, and his career with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) would span 35 years and four continents.

Did he share his predecessor’s enthusiasm for wine?

Certainly he didn’t find official Company vine plantings much to get excited about. According to the instructions Van Riebeeck had left for him, there were precisely 832 vines planted in the Company’s Garden and at the fort, of which only 82 had produced fruit, while the remaining 750 comprised young rooted vines.

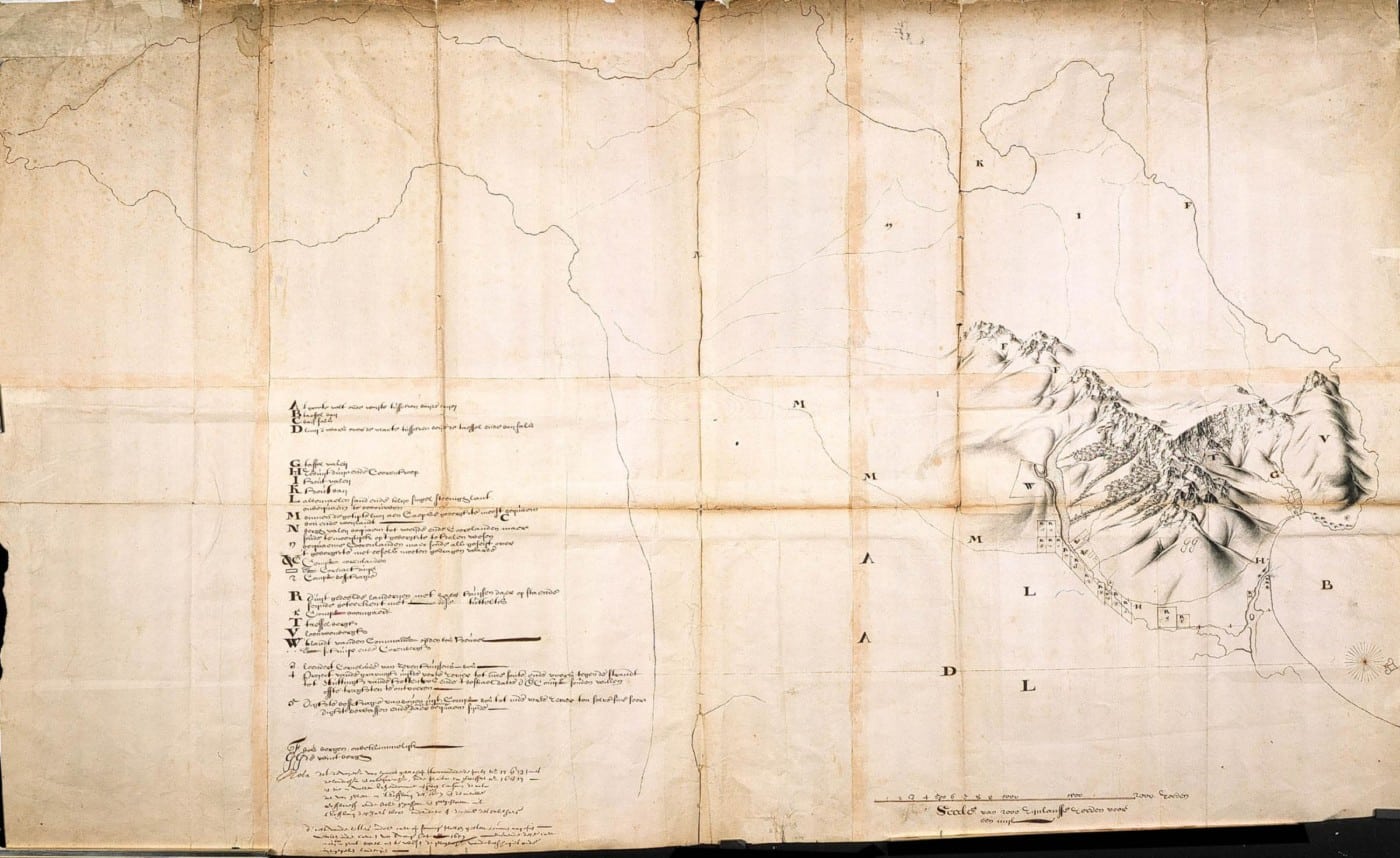

Map of estates in the Table Bay area awarded to former employees of the VOC by land surveyor Peter Potter circa 1658.

However, Van Riebeeck’s ‘own’ vines at Bosheuvel were ‘thriving very beautifully’ (even if there weren’t quite 10-12,000 planted, as he claimed) and some of the vrijburghers farming along the Liesbeeck River (from present-day Mowbray to Bishopscourt) had also started establishing vineyards (we’ll meet some of them next time, most notably the man who would purchase Bosheuvel in November 1665).

From the start, Wagenaar took a fair amount of interest in Bosheuvel, travelling there every August – ‘the right time’ – to oversee the pruning and tying of vines, and to make sure they were being ‘properly manured’. He also visited every February when the grapes were ‘rapidly ripening’, his records showing that Bosheuvel production grew from less than one aum (140 litres) in 1664 to 1½ leaguers (about 845 litres) in 1666, when it was decided to make some French Muscadel because of the ‘aengename, lieffelyke geurs’ (pleasant lovely fragrances) as well as some ‘rynsche rincouwer’ (Rheingauer) or ‘moeslaer’ (Mosel).

A sample of vintage 1666 was sent to VOC directors, the Lords XVII, who acknowledged it positively in their despatch of 23 October 1666: ‘The wine sent us as a specimen, we found, contrary to expectation, very well tasted.’

Wagenaar seems to have focused most of his attention on the so-called Company’s Orchard, which had been established near an enormous, round clump of thorn bushes duly named ‘De Ronde Doorn Boschje’ (later referred to as Rondebosje, today Rondebosch in Cape Town’s southern suburbs). Van Riebeeck had first sown wheat, rice and oats there in 1656 ‘to see if they would definitely suffer less there from the strong winds’ (they did, leading to the establishment of a large granary or Groote Schuur nearby) and in the meantime he had also planted some 1,000 vine stocks there.

Later known as Rustenburg, with its ‘excellent pleasure-house’ for hosting high-ranking officials, the Company’s Orchard was situated on land that now incorporates Rustenburg Girls’ Junior School as well as much of the University of Cape Town. In the early 1660s, however, it was still pretty untamed country, with Wagenaar reporting on 17 November 1663 that a lion had ‘again’ killed an ox near the Schuur. The following week he reported heavy rains: ‘Certainly good for the pastures and our cabbages, but for the wine, melons and watermelons, too cold and injurious at this time of the year.’

In July 1664 he was delighted to discover that the first mate of the Walcheren, Pieter Adriaan van Aarnhem, was knowledgeable about viticulture. On 8 July they went together to the Rondebosje orchard, where Wagenaar reported: ‘He planted some hockaner [Hochheimer] vine slips, which he had himself brought from Germany. Time will show the result. He also left us the model of a wine press that we might have a bigger one made from it.’

On 7 August 1664, Wagenaar had a ‘suitable’ new piece of ground prepared for vines, and enclosed with thick stakes ‘so that the young shoots may not again be eaten off by the rhebucks or wild pigs (as they did in the other new vineyard behind the schuur)’. On 13 August 1664, he duly reported: ‘Over 400 vine cuttings were put into the ground today, whilst tomorrow fully 600 more will be planted.’

The following June and July, he oversaw the planting of a further 4,000 vine stokkies that had been taken from Bosheuvel, but alas he wouldn’t stay at the Cape long enough to see what became of them, departing for Batavia on 27 September 1666 following the death of his wife.

Nonetheless, Wagenaar’s winegrowing achievements at the Rondebosje were noted by a French East India Company official named Urbain Souchu De Rennefort, who visited the Company’s Orchard on 29 December 1666. He marvelled at the herbs, flowers and vegetables, the olive trees ‘heavily laden with fruit’ and especially the two arpents (almost 7,000 square metres) of vines. ‘The grapes would be fully ripe in another three weeks,’ he wrote. ‘Some bunches of them were already eatable, and their wine, according to those who had drunk it, was similar to that of the Rhine.’

By 1673, the Cape’s sixth commander, Isbrand Goske was able to report that production at Rondebosje/Rustenburg had increased to five leaguers (11,260 litres), and by 1684, when 10th commander Simon van der Stel was living at Rustenburg, there were 100,000 vines planted there, deemed capable of producing up to 100 leaguers (53,000 litres) in a good year.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First we need to meet some of the vrijburghers who had initially been ‘very indifferent’ about planting vineyards but whose combined 1671 grape harvest (as delivered to and pressed by the Company) yielded over 23,000 litres of ‘goede en smakelycke’ (good and tasty) wine – almost 10 times more than was produced from the Company’s own fruit.

Bibliography

Leibbrandt, HCV: Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope (Journal, 1662-1670; Journal, 1671-1674 & 1676; Letters despatched from the Cape, 1652-1662, parts 2-3), originally published by W.A. Richards & Sons, 1896-1905, digitised by University of California Libraries (https://archive.org)

Moodie, Donald: The Record; or Official Papers relative to the Condition and Treatment of the Native Tribes of South Africa, Part 1. 1649-1720, Cape Town 1838-39, digitised by the Internet Archive, 2015 (https://archive.org)

Raven-Hart, R: Cape Good Hope 1652-1702: The First Fifty Years of Dutch Colonisation as seen by Callers. A.A. Balkema, 1971

Van Rensburg, J.I: Die Geskiedenis van die Wingerdkultuur in Suid-Afrika tuidens die Eerste Eeu, 1652-1752. MA Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, 1930

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Hennie Coetzee | 10 July 2018

Another fascinating article! So the Germans made an enormous impression on our wine industry.

Joanne Gibson | 10 July 2018

Just wait! I have been quite astonished to discover how many of the vrijburghers were German rather than Dutch (as is often assumed), particularly those who put down permanent roots, among them Cloete (Klauten), Eksteen (Eckstein), Geldenhuys (Gildenhausen), Heyns – and don’t forget Coetzee (Kotze)!

Tim James | 10 July 2018

The prospect of a series of notes on early Cape winemaking from Joanne is a good one. But there’s so far been a silence about one aspect of a history that has a particularly dark side. Joanne did allude to the Khoi in her first piece (the first Dutch-Khoi war is reckoned to have taken place from 1658-1660, as a result of settlers moving on to their grazing and hunting grounds). In the two articles thus far, however, there’s no mention of the slaves on whose labour the Cape wine industry was substantially founded.

It was not Van Riebeek who “planted 1200 cuttings” on Bosheuvel in 1658; he himself notes that it was done “with the aid of certain free burghers and some slaves”. From within months of landing, Van Riebeek, a slaveowner himself, had been asking for slaves to be sent here, and it was in 1658 that the first shipment arrived. Some of the slaves were assigned to free burghers. Already the slaves outnumbered the white population, a situation that was to persist for a very long time, with huge consequences for the structure (and mentality) of the local wine industry – and South Africa as a whole, of course. In the early 19th century, wine farmers owned an average of 16 slaves. By 1820, 14 years before slavery was abolished in the colony, the Cape’s total slave population was nearly 32 000.

So while it’s pleasant to illustrate and debate the contributions of the Dutch, Germans and French, we really mustn’t have yet another sanitised history of Cape wine in which the enforced role of slaves is ignored – however much the wine industry as a whole tries to forget it.

Joanne Gibson | 11 July 2018

Thanks for the nudge, Tim. It’s an indisputable and tragic fact that the SA wine industry was built on the backs of slaves and I do intend to try and tackle the issue (as I mentioned in one of my comments on the first post). I now realise I’d better do so sooner rather than later.

Just briefly, I find it quite interesting that the VOC’s government in Batavia was reluctant to send slaves to the Cape (despite the fact that slavery was pretty much universal practice at the time, even within the warlordism and caste systems of many indigenous African and Asian societies). In a letter written to Van Riebeeck on 13 December 1658 (almost seven years after he arrived at the Cape and some seven months after the first slaves had been brought from Guinea and Angola), the Council of India wrote: ‘In our opinion, the colony should be worked and established by Europeans, and not by slaves, as our nation is so constituted that as soon as they have the convenience of slaves they become lazy and unwilling to put forth their hands to work.’

Yup!

It is not my intention to ‘sanitise’ let alone ‘glamourise’ those early (white) settlers. Most of them were illiterate soldiers of fortune, ‘churls’ who, back home in Europe, would have BEEN the servants rather than having servants. (And, ironically, many of the children born into slavery at the Cape would receive a better education than many of the children born into freedom on the farms…)

But against seemingly impossibly odds, they – along with their slaves – did start a wine industry, and I’ll do my best to tell their story (good and bad).

Jared | 8 August 2018

Very informative and helpful response Joanne. I look forward to the next articles with earnestness.

Melissa Sutherland | 27 August 2018

Interesting article. Thanks.