SA wine history: A ‘rough’ start for Blaauwklippen

By Joanne Gibson, 23 July 2019

9

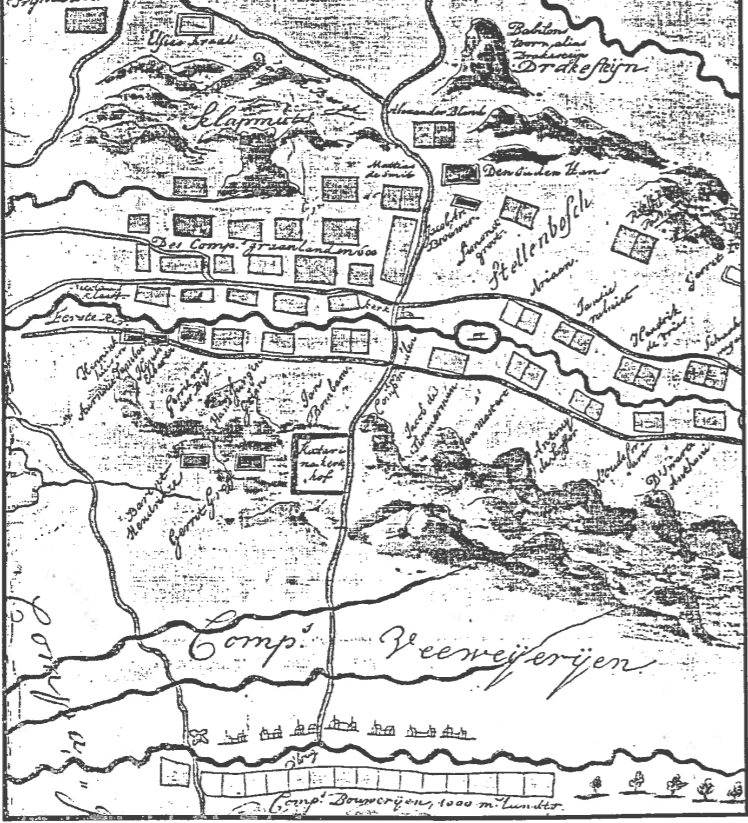

Alongside Steenberg and Rustenberg, the third South African wine farm claiming a founding date of 1682 is Blaauwklippen, whose position is indicated on a fairly crude, circa 1688-1690 map where the name ‘Gerrit Groff’ is written quite prominently.

from the Cape Town Archives Repository, Ref: M1/273)

Born in about 1657, Gerrit ‘Grof’ Visser was the son of Jan Coenraad Visser, who arrived at the Cape from Ommen in the Netherlands on 28 April 1658 and became known as Jan Grof (the nickname ‘grof’ almost certainly not indicating that he was ‘tall’, as one descendant claims on a genealogy website, but rather that he was a little rougher around the edges than most – and that was saying something).

After becoming a vrijburgher on 30 September 1659, Grof/Visser senior was granted land in the Liesbeeck Valley, only to be singled out as one of the new colony’s laziest farmers on 8 September 1660, when he and his neighbour Pieter Visagie were accused of ‘becoming daily more indifferent to their work…without displaying any zeal whatever in the rearing of wheat’.

The Dutch East India Company’s agricultural superintendent at the Cape was duly instructed to ‘urge them on to their work as if they were still in the Company’s service’ so it’s perhaps not surprising that they were caught attempting to stow away the following March, with Visser testifying in his defence that the homebound crew had cried out from the ships: ‘Get into the boats, go with us; what do you do in this cursed land? We would rather be hanged than die in this damned country!’

In an attempt to make Visser ‘disinclined to desert’ (probably because he showed some prowess as a hunter, if not as a farmer), the Company financed passage to the Cape for his wife Geertjen Gerrits and three children – among them, five-year-old Gerrit – who all arrived on 4 February 1662, only to discover that Visser had in the meantime fathered a child with the slave woman Lijsbeth van Bengal.

Over the coming decades, Visser’s name would appear in the record books for various other reasons, ranging from illegal bartering to (wait for it) his wife’s beheading by the slave Claes van Malabar in 1692 (after which, incidentally, the septuagenarian would procreate at least three times with his slave Maria van Negapatnam).

In contrast, Gerrit Visser’s relatively modest claim to fame is that on 4 August 1675 he became the first vrijburgher to marry a Cape-born woman. She was Jannetjie Thielemans, the 15-year-old daughter of Thieleman Hendriks (the chap who stabbed Hans Ras on the day of his marriage to Catharina Ustings of Steenberg fame) and Mayken van den Berg, whose ‘life of thievery’ culminated in her banishment to Mauritius in 1677, but only after being pilloried with a rice sack over her head, severely flogged and branded with the sign of a gallows on her back!

Gerrit’s older sister Maria also achieved some notoriety in the mid-1670s. Married in her mid-teens, sometime before 1664, to her father’s hunting buddy, Willem Willemse, she went on to have two children with his knecht, Ockert Cornelissen, albeit only after her husband had stowed away on a passing ship (to escape punishment for fatally wounding a Khoi servant who’d broken his favourite beer mug) and been banished in perpetuity. Pardoned just two years later, however, Willemse was permitted to return to the Cape, where he and his wife came to blows over what the authorities now called her sehr lichtvaardigh (very licentious) behaviour. To cut a long story short, they kissed and made up, but in 1677 were sent to Mauritius to keep Willemse out of sight of the Khoi, who no doubt (quite rightly) felt that justice had not been served.

After all this excitement, it seems Gerrit and Jannetjie Visser kept a low profile. The Opgaafrolle (tax records) show that in 1682 they had two sons, one daughter, one female slave, one horse and 15 cattle. They were growing corn and barley but had no vines planted. By 1688, they still had only the one slave and horse, but they now had three sons, three daughters, 30 cattle, 200 sheep and 1,000 vines planted.

In 1690, however, they decided to sell up. As no official grant had yet been issued, the landdrost Johannes Mulder surveyed the farm (huijs en erv) on 9 November 1690 and, on the same day, transferred it to Guillaume ‘Willem’ Nel, a French Huguenot who’d arrived at the Cape in 1688 and was a tailor (kleermaker) by profession rather than claiming any knowledge of winemaking.

Nel had 3,000 vines planted by 1692, and only briefly (in 1709) did this number increase to 6,000 vines, after which it shrank again to 3,000. It seems both Nel and his wife Jeanne de la Batte (Jannetjie Labat) had to make ends meet by working intermittently for Adam Tas, the leader of the opposition against governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel of Vergelegen fame.

Nonetheless, it was Nel who named the farm ‘De Blaauwe Klippen’, and he somehow managed to hang on to it until 1722 when he sold it to his daughter Jeanne’s second husband, Barend Pietersz from Wesel in Germany, for 1,000 guilders. Pietersz, in turn, sold ‘Blaauwe Klippen’ to George Christoffel Grommet in 1742 for 775 guilders – in other words, 22.5% less than he had paid for it 20 years previously.

Suffice it to say that becoming a successful wine farmer during those early days of European settlement at the Cape wasn’t easy. According to research published on Blaauwklippen’s website, Gerrit Visser was sent back to Holland in 1693 because ‘the Company judged him to be of no use to the settlement’ but I’ve found him living in the Liesbeeck Valley in 1693, having purchased a section of the large property Reygersdal, where he and his family would live until moving back to Stellenbosch in 1708.

By which time, incidentally, Gerrit’s daughter Aeltie (baptised on 2 June 1680) was following in the footsteps of her ‘grof’ relatives by having four children with Jasper Gommers despite still being married to Jacob Petrus Bodenstein (for which hoerery en onkuisheid she was deported to the Netherlands in 1712).

In delicious contrast, Jan Grof’s illegitimate daughter with Lijsbeth van Bengale, born in 1660 and known in adulthood as Margaretha Jansz Visser, became the first schoolmistress at the Company’s Slave Lodge, not to mention the mother-in-law of Johannes Colijn of Constantia fame. And one of his daughters with Maria van Nagapatnam, known as Susanna Visser, married Hans Heinrich Hatting in 1716, thereby becoming the mistress of another early Stellenbosch wine farm, Spier.

But I think that’s probably enough for today.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blaauwklippen

Leibbrandt, HCV: Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope (Letters despatched from the Cape, 1652-1662, vol iii), originally published by W.A. Richards & Sons, 1896-1905, digitised by University of California Libraries (https://archive.org)

Robinson, Helen: The Villages of the Liesbeeck, From the Sea to the Source, Houghton House, Cape Town, 2011

Upham, Mansell: Hell and Paradise…Hope on Constantia: Jan Grof (died ante 1700) and his extended family at the Cape of Good Hope, Remarkable Writing on First Fifty Years, 2012

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Robert Donald Campbell | 22 March 2024

This history seems to have been copied from other sources.

No mention is made of the Hoffman family, Dirk and his brother Bernard, who owned Blaauklippen. Each “so-called” historian seems to merely copy or extract from the previous one, thereby distorting and corrupting history.

Please answer this assertion and present proper facts.

Kwispedoor | 25 March 2024

Hi Robert. This history snippet only seems to deal with the early period until 1742. Did the Hoffmans own Blaauwklippen during those years?

Joanne Gibson | 25 March 2024

Unless the records are incorrect, the Hoffman family only acquired Blaauwklippen (please note correct spelling) in 1762 (T3702 dated 13/01/1762), and clearly this particular article only dealt with the farm’s very early history. I mentioned the ‘later’ 1742 transfer of Blaauwklippen to George Christoffel Grommet in passing only to show that its value had sadly declined over the two previous decades.

Yes, indeed, the owner after Grommet was Johan ‘Jan’ Bernhard Hoffman. My understanding is that he in turn transferred ownership to his 21-year-old son Dirk Wouter in 1773 (T4566 dated 26/06/1773), with a few intriguing months in between (26/03/1771-23/12/1771) of presumably unhappy ownership by the divorcing couple, Johan Joachim Sweedberg and Johanna Christina Derlitsch. Thank you for your comment, reminding me how many interesting stories remain to be told, without distortion and corruption.

Udo Göebel | 21 March 2023

About: Jan Grof (the nickname ‘grof’ almost certainly not indicating that he was ‘tall’, as one descendant claims on a genealogy website, but rather that he was a little rougher around the edges than most – and that was saying something).

I am not an expert, but it could mean other things as well. Like that he was rich or had big hands or was rude/impolite or non religious.

Nice read though!

Gideon | 19 March 2023

Hi Joanne, I am Gideon Pieters. Barend Pietersz from Wesel is my family’s progenitor. Do you perhaps have more info of his ownership 1722-1742 of the Blaauwklippen Farm?

Joanne Gibson | 20 March 2023

Hi Gideon,

It seems Guillaume Nel provided for his daughters by selling both of his farms to his sons-in-law, rather than transferring them to his own sons. Thus Arij van Jaarsveld (married to Cornelia) bought Bootmansdrift (Wellington) in 1721 while Blaauwklippen was transferred to Barend Pieterz (married to Jeanne) on 13 January 1722.

If you consider that Barend paid his father-in-law 1,000 guilders and sold the farm two decades later for only 775 guilders, then it doesn’t appear that he was a very prosperous farmer. In fact, I’ve had a look at the 1741 muster roll (in which vrijburghers declared their possessions and farm production on an annual basis) and Barend and Jeanne are listed that year with three daughters (their adult son Hermanus listed separately below) and all they could declare was 10 head of cattle – no other livestock, and no crops let alone vineyards and wine production…

Hope that helps!

Anne Bursey | 29 January 2023

Such interesting history – particularly since Guillame Willem Nel is my 7th great grandfather. Are there any surviving original buildings?

Kwispedoor | 23 July 2019

Hi, Joanne. I’m wondering if Jasper Gommers was also deported for his ‘hoerery en onkuisheid’? 😝

Joanne Gibson | 23 July 2019

Apparently he was arrested, and relieved of his duties as court messenger…

According to Prof AM Hugo in the Dagboek van Adam Tas (Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 1970), Jasper Gommers “was een van die ongure karakters van wie ons lees dat hy jare lank ‘in hoererije en onkuijsheit’ met ‘n ander man se vrou geleef het, vier kinders by haar verwek en die kinders skromelik verwaarloos het, sodat hy self uiteindelik onder arres geplaas is, die vrou na Holland gedeporteer is, en die verwaarloosde kinders onder die sorg van die kerkraad geplaas moes word”. (C. 510, II, bl. 711 v.; Res. Kerkraad, Stellenbosch, 31 Jan., 14 Feb. 1712.)