Tim James: Pinot noir, present and past

By Tim James, 10 April 2020

6

Pinot noir was on my mind this evening. I looked at what I had available and thought that the bottle of Crystallum Peter Max 2012 looked more ready than most to be exsanguinated. (Inebriated digression: that magnificent verb, meaning “let forth blood” suddenly came to me while writing this. I understand why. I recently finished reading The Mirror & the Light, the third and final volume of Hilary Mantel’s justly celebrated novel about Thomas Cromwell, the great minister of England’s Henry VIII. That volume ends with his decapitation, but the memorable verb comes from the end of volume 2, and the beheading of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife. The culminating scene is described in the present tense, so: “The body exsanguinates.”

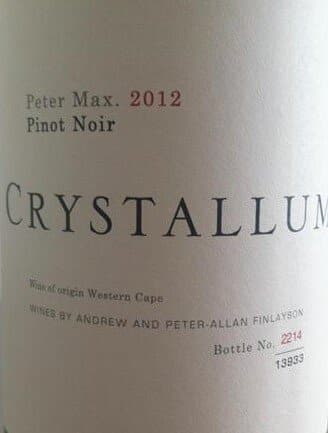

Pinot noir was on my mind this evening. I looked at what I had available and thought that the bottle of Crystallum Peter Max 2012 looked more ready than most to be exsanguinated. (Inebriated digression: that magnificent verb, meaning “let forth blood” suddenly came to me while writing this. I understand why. I recently finished reading The Mirror & the Light, the third and final volume of Hilary Mantel’s justly celebrated novel about Thomas Cromwell, the great minister of England’s Henry VIII. That volume ends with his decapitation, but the memorable verb comes from the end of volume 2, and the beheading of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife. The culminating scene is described in the present tense, so: “The body exsanguinates.”

It’s a shuddering literary moment and the lingering Latinate word somehow adds to the awefulness.

Totally inappropriate, really, to describing pouring Peter-Allan Finlayson’s second-label pinot. Though less dense in colour, it is as rich and full as blood, I suppose. No, forget Anne Boleyn. It’s delicious, mature wine, remarkably youthful still (great colour, with nice mahogany on the rim), more robust than elegantly delicate. Quite a bit of precipitated muck in the bottom of the glass is testimony to the restrained hand of the winemaker. It didn’t occur to me to do, but I’d advise anyone lucky to have some of this wine left to decant it – though don’t necessarily be in a hurry to do so.

Incidentally, while I’m here, I should mention that this evening I still had a glassful of an even superior wine that I opened the previous day, one that I’ve glowed about before: Reyneke Reserve Red 2010, the last one made with cabernet as well as syrah. A superb wine of international standing. At ten years old I reckon it’s at it’s best, though no hurry to drink up.

Back to pinot. I’ve been thinking of the grape, as I was contacted by someone who’s researching the history of the variety in South Africa for the Pinot Noir Association intro. (I’m delighted about that, and hope some real effort goes into it; I continually find it depressing how little interest the varietal associations and most of the established estates show in the past and how they got to the present.)

It’s not a topic I was able to help greatly with, but I could at least point out that, contrary to general understanding, Muratie was not, apparently, the first estate in the Cape to plant pinot noir – though it certainly was the first to produce a pinot wine. Muratie’s plantings (though, typically, one looks in vain to the estate’s website for information, despite a self-proclaimed “passion for preserving our rich heritage”) date from the latter 1920s, after George Canitz bought the farm in 1925. His good friend Professor Perold was much involved, and introduced pinot noir – presumably from the Stellenbosch University Farm. (In Perold’s Treatise on Viticulture of 1926-27, he cites only these University plantings.)

However, by this time Perold had already helped another Stellenbosch estate to plant pinot: Alto ( I described recently how Alto had been one of the earliest Cape farms to plant syrah). The sources I have for this are possibly contradictory, up to a point. Graham Knox’s indispensable Estate Wines of South Africa (second edition, 1982), says that “during 1920 Hennie Malan planted Cabernet Sauvignon, Shiraz, Pinot noir, Gamay and Cinsaut”. However, Fanie de Jongh’s Encyclopedia of South African Wine (second edition, 1981) seems to suggest that it was cinsaut that was first planted there, and that “In consultation with Prof. Perold, the noble varieties Cabernet, Pinot Noir and Shiraz were selected for new plantings on Alto during the 1924 and 1925 planting seasons”.

Probably these two accounts differ because of faulty recollections (always a problem for historians). But, whichever version is correct, pinot noir was planted on Alto before it was planted on Muratie. Though, unlike on Muratie, it came to nothing on Alto. It seems pinot was too early a ripener to be a useful partner to the varieties (notably cab, syrah and cinsaut) that went into the blend that was to become famous as Alto Rouge.

De Jongh’s Encyclopedia also has a statistic that is interesting for the growth of the pinot noir vineyard in the Cape: “The enormous popularity achieved by this variety in recent years is reflected by the total of 268 870 vines counted in local vineyards as against the 30 159 of 1973. Exactly 85% of the total are to be found in the Paarl and Stellenbosch Districts”.

The first edition of Platter, in 1980, also notes the burgeoning of pinot plantings in the 1970s, and reports “several new vineyards in South Africa … making clean, lively ‘lean’ lightish wines, introducing new flavours to our red range”. The estates were becoming more significant at this time, following their protection by the Win of Origin legislation of 1973, and presumably this is what’s behind the new interest in pinot noir. By my count, there are seven pinots listed in that 1980 Platter: from Blaauwklippen, Delheim, Groot Constantia, Kanonkop (“very young vineyards”), Landskroon, Muratie, and Rustenberg. Consider the reputation of pinot from most of those estates now, and realise how much more portentous was the almost contemporary (1981) maiden pinot from Hamilton Russell Vineyards in the Hemel-en-Aarde – it was called Grand Vin Noir, for reasons that constitute quite another story, featuring the overlord KWV as joint hero….

My Hemel-en-Aarde pinot of this evening, Crystallum Peter Max 2012, is depressingly, alarmingly, nearly done. Worth noting, is that it is emphatically not from the BK5 clone that went into that significantly pioneering Hamilton Russell wine.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. He is a taster (and associate editor) for Platter’s. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

Christian Eedes | 24 April 2020

Via email from Rijk Melck, owner of Muratie:

We have such rich history here at Muratie ,it actually warrants more than a website search. Prof Abraham Perold is obviously the playmaker in the story. I have just read the book Abraham Perold –Wegwyser van ons Wingerdbou, written by R U Kenney and published in 1981.

Abraham Perold was born in Dal Josaphat 1880.

Tertiary education at University of The Cape Of Good Hope (UCT). First class pass in subjects Mathematics, Physics and Science. Receives a bursary to study further in Germany 1902.

He returns in 1906 and lectures at UCT in Science. Here he publishes his first book: “Wijnbou in Frankrijk en hier”. He is then sent by the Cape Government to study the winemaking and viticulture abroad – 1907. He meets his future wife in Halle, Germany. (This is where is German connection starts – years later the friendship with G P Canitz and Baron von Carlowitz (Uitkyk).

1912: he is made head of Elsenburg Agricultural college

1917: he is promoted to Professor in Viticulture and Oenology at Stellenbosch University. This is where the Pinot Noir story might start – one of his first group of students were: Paul Oswald Sauer, H J (Manie ) Malan of Alto, S J Botha, J S Van der Spuy and CT van der Merwe. I cannot find any reference that mentions that the two of them (Manie and Prof) planted Pinot Noir.

What I do know from our research at Muratie – done by Helena Sheffler (D Phil) is that George Paul Canitz bought Muratie in 1926. I have his day journal – fascinating. He writes in there that he made an impulsive decision to buy Muratie but that Professor Perold, great friend of his said that he would help Canitz develop the farm – the first vines from Burgundy arrived in 1927 – Pinot Noir and Gamay.

Canitz was living in Mark Straat whilst he was teaching art at the University of Stellenbosch.

Baron Von Carlowitz bought Uitkyk in 1929, Perold arranged for them to plant Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cinsaut and Shiraz. Von Carlowitz mentions that the only place that the Pinot Noir took was at Muratie.

I guess some people might find all this info boring. As an old school boy, I find it fascinating. As they say “ nostalgia is not what it used to be…”.

Eddie Turner | 11 April 2020

Hi Tim As a matter of interest the first Meerlust Pinot Noir was produced in 1980.

Tim James | 11 April 2020

Thanks Eddie. That is interesting and I hadn’t realised. It means (I think) that Meerlust’s is the Cape’s oldest pinot label, after Muratie’s, still in existence. All those other pioneers I mentioned have long since given up. By the way I was really sorry to hear of the sadly early death of Meerlust’s fine, long-time viticulturist, Roelie Joubert. It will be a hard gap to fill.

Simon | 10 April 2020

Désolé Gilles. On this one you’ve not been informed correctly. Pinot Noir, be it from Vosne Romanee, Gevrey Chambertin, Oregan, Otago or Hemel and Aarde – all can be decanted and does better with aeration. The same “rules” apply as for other varieties. If young, decant. If middle aged, no point in decanting – pour a glass and aerate in glass. If very old and sediment is evident, gently decant and consume immediately otherwise it will fall flat and die. Same set of rules apply for any variety.

Tim James | 10 April 2020

Hi Gilles. I tend to avoid “rules” like that – and in fact there is no real consensus on this point, though I see that it is much debated. Decanting is always a controversial topic, in fact, for all wines. As far as I can see, here the discussion usually revolves around whether a pinot is too delicate. I suggested it because the wine was throwing some sediment – not because it needed rapid brutal aeration in order to help it open up. But it’s also a robust, quite youthful wine that could well cope with aeration. In fact, I’ve just tried the bit left in the bottle for 24 hours (at least the equivalent of decanting) and the wine is doing just fine, and certainly hasn’t fallen flat. There’s another controversial matter – how long you can keep an open bottle ( I know few youngish wines than don’t taste better on the second day). And again, I’d say there are no rules. As usual, the more I learn, the less I’m certain about!

GillesP | 10 April 2020

Hello Tim. I am very surprised you would decant a Pinot Noir. It is usually considered a no no or maybe for 30mn at the most. Otherwise the wine falls flat very quickly but I am sure you know that already.