Tim James: Putting South African Grenache in a new context

By Tim James, 4 November 2024

2

It was a steep and sudden learning curve for me about the possibilities of garnacha. Grenache, if you prefer, though really we should call it garnacha, given that it’s a Spanish grape – but such is the prestige of vinous France that the French version is the more widely used name. It was some emphatically Spanish wines, however, that started me rethinking about the local versions of the grape.

I’ve always enjoyed grenache-based Châteauneuf-du-Pape from the southern Rhône and thought it had much that Cape winemakers, with a rather similar climate, could learn from: notably, how to make ripe, full-bodied wines that are as savoury as they are fruit-filled and, above all, with an element of freshness and genuinely dry-tasting on the finish – both of those last being attributes too often lacking in the established style of red wines here. I’d vaguely concluded that the answer lay partly in acidity and partly in fermenting fully dry – if you have an alcohol level over 14% and a residual sugar over two grams per litre, the chance of genuine dryness on the palate seems to be pretty well zip. (Of course, a lot of people seem to enjoy the big, ripe, fruity sweetness of, say, the typical Stellenbosch cab; I don’t.) But a tasting this last weekend has made me wonder if a significant part of the answer might be in the grape variety. Not to mention the wider growing conditions.

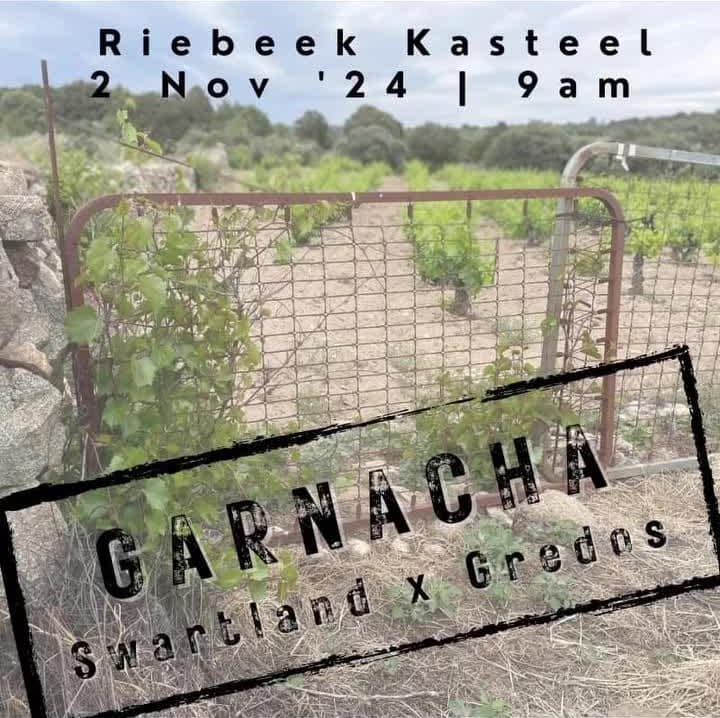

The tasting was organised for the Swartland Wine and Olive Route in the village of Riebeek-Kasteel, just before the centre of the village was filled with crowds at this year’s Street Party of regional winemakers pouring their wines (good food also available too, with your not-exactly-cheap-but probably-reasonable ticket). The formal, sit-down tasting featured six garnacha wines from the mountainous Sierra de Gredos region of west-central Spain (between Madrid and Portugal), and two Swartland grenaches, from David&Nadia and Badenhorst.

I can’t see much point in trying to squeeze in much of the story of the Gredos area here, or even specifying the wines we had at the tasting, which aren’t available locally. If anyone is interested, it’s all beautifully described by Margaret Rand for the World of Fine Wine, in a 2020 article available free online. Sierra de Gredos is a rugged area of mostly granitic (some schistous) slopes and valleys at 500–1200 metres altitude, its viticulture having fed the coops that characterised Spain as much as they did South Africa in not dissimilar times of political bureaucratic control and international disdain. Winegrowing was in steady decline here during the 20th century, until a new, adventurous and ambitious generation of growers and winemakers emerged or arrived in Spain’s wine renaissance (at much the same time as the Swartland and its chenin treasure were being rediscovered) to revel in the old garnacha bushvines surviving in small, scattered plots. Fame and international appreciation followed quickly.

There’s also a fine Gredos white produced from albillo, but it is the garnacha that has been something of a revelation for many of the Swartland new wave – as it now has been for me. The six we tasted were variations on a theme of vibrant freshness, aromatic character that was too complex and forceful to be merely charming, subtle intensity of flavour, convincing texture, and an interwoven structure of tannin and succulent acidity. It would have been difficult, I think, for anyone to have detected in the overwhelming freshness, focus and powerful delicacy that these were ripe wines of 14.5% alcohol or more.

I had had no experience of Gredos garnacha, but I have some of those of Priorat, as well as Châteauneuf, and these were different: more along the “Burgundian”, pinot-noir-ish lines that most of the best Cape versions aim at. It seems generally regarded as the most elegant expression of the grape in Spain.

And the Cape wines we tasted? They certainly share the aesthetic approach of the Gredos wines – as do many Cape examples, which tend to belong to the “light, aromatic red” category (what Eben Sadie only slightly disparagingly calls hipster wines – from which he doesn’t necessarily exclude his own grenache, the Soldaat from Piekenierskloof). I’ve always found the David & Nadia Grenache a touch too light and ethereal for my taste, and the 2021 here was very much in that style, and without the weight, seriousness, texture and complexity of the riper Gredos wines. (Incidentally, Christian Eedes has scored it 97, Platter’s 95, Tim Atkin 93.) Badenhorst Raaigras is from the oldest grenache vineyard in the Cape, 12 rows planted in 1952, and it’s perhaps that, together with a little more ripeness and alcohol, that gives it a greater vinous intensity, finesse, complexity and structure. (94 points from me in Platter’s, 94 from Tim Atkin, 93 from Christian.)

Very pleasing though these two wines were, it must be said that they didn’t stand comparison to the Gredos wines in terms of sheer quality. Certainly not for me, and, when I asked around, including from Swartland winemakers, that was the general opinion (though there was one person whose palate I respect who thought otherwise). It’s the altitude that makes the difference in potential – that seemed the commonest reason given. It seems to me probable that most of the scores cited above for the Swartland are actually too high in international terms, though scoring inflation is also to blame, scrunching up wines too much together at the higher end; also I feel that some international critics are often over-generous in their local scoring, for various reasons. The Gredos wines we tasted were good examples, I was told by a winemaker who knows Spanish wines well, but not the A list of very expensive, high-90s-scoring wines.

It’s not often enough pointed out that a real problem for local professional critics and judges is a lack of exposure to a wide range of fine international examples; we are mostly pretty provincial, in fact…. It was notable at this rare tasting that in the room there were extremely few of the people who most frequently judge and comment on local wines (I saw Angela Lloyd; perhaps I missed others), and that is unquestionably not an uncommon situation. How can we pretend to make confident judgements if we don’t have experience of the world’s benchmarks?

As for grenache, it is becoming an increasingly important variety here, especially as it is more suited than many black varieties to an ever-hotter, ever-drier climate. Greater vine age and finding the best terroirs will no doubt do much to improve things – as will getting over the fascination with very light wines (though that’s arguably the best approach with younger vines). It’s good to be reminded just what a wonderful grape grenache can be and what there is to look forward to. For example, I had an interesting conversation at the Street Party, after the tasting, with Stompie Meyer of Mother Rock. Talking of the significance of altitude, he told me he has a maturing grenache vineyard on his farm high on Swartland’s Piketberg Mountain, for which he has great hopes. Next year, the grapes will produce wine for a blend; as the vines mature, a predominantly, or solely, grenache wine will emerge. Sounds interesting.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Greg Sherwood | 5 November 2024

Anyone interested in the international Grenache debate and also Gredos top end wines specifically can read about our annual tasting of the most expensive and sought after examples here…

https://gregsherwoodmw.com/2024/07/08/the-judgement-of-wimbledon-blind-tasting-2024-a-celebration-of-glorious-grenache/

No expense spared… making for a very interesting blind annual tasting.

Jos | 5 November 2024

Surely there also has to be a mention given to the cost of these wines? Spanish wines are still generally relatively inexpensive compared to French and even Italian wines, but South Africa’s most expensive grenaches cap out at about R500. And those are the outliers.

Spanish top dogs go for multiple thousands a bottle and the premium ones can still go for way more than our most expensive examples.

It also feels like the variety just isn’t particularly popular here. When it comes to red’s, people seem to prefer the Stellenbosch varieties. Restaurants often times have limited to no grenache options on the menu.

So it makes sense that we would be trailing Spain on this front given that we simply do not have that many winemakers making serious wines from grenache.