Tim James: Vineyards and varieties – where we are now and where we were

By Tim James, 30 October 2023

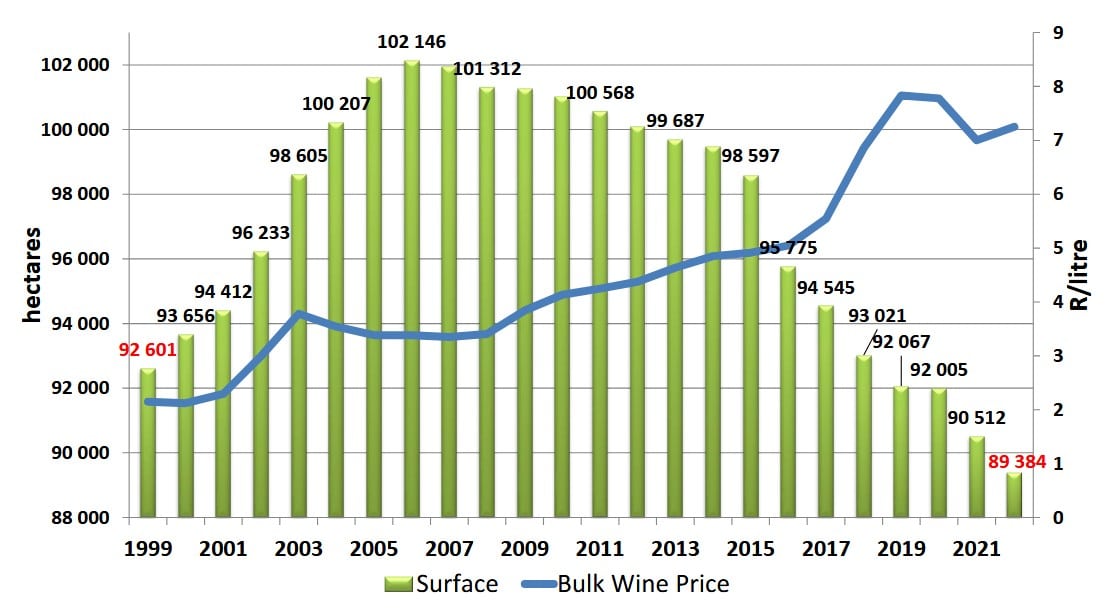

If its scores you’re wanting rather than information about South African vineyards and varieties, you should go now, even if the headline hadn’t scared you off already. Or, for that matter, if you believe in the implications of that rather silly saying about there being “lies, damn lies and statistics”. After offering some numbers and thoughts about consumption (South Africans drinking more wine these days, etc) a few weeks ago, I’ve delved into some of the latest statistics about the South African vineyards that are available on the Sawis website, and have what I think are some of the fascinating highlights for you. (As well as a number of Excel spreadsheets, there’s also a good infographic showing the current situation essentials, and a Powerpoint presentation on plantings, from which the bar-chart below was taken.)

We can begin with the overall picture that some commentators seem to lament. The total area of vineyard, diminishing since its highpoint in 2006, has continued to decline. It’s now, at the end of 2022 that is, down to just under 90 000 hectares. As I remarked in considering that earlier set of stats, this is probably something to celebrate, if – as I hope – some poor quality bulk grape producers are now using water and sunshine to produce crops that the country and the world are more in need of.

Actually, it’s worth noting that this hectarage reduction is simply taking the number back to what it was around 1994, when it really took off in response to the return of South Africa to the world market. The bar-chart goes back only to 1999, but you can see how steep the curve is – much steeper than the post-2006 decline. At least some of all that planting must have been pretty opportunist and speculative – although it did also reflect the welcome expansion of wine-growing in the Cape South Coast area (Elgin, Hemel-en-Aarde, agulhas, etc). It’s also worth noting the jagged but ever-rising blue line on the chart, reflecting the increased price for bulk wine – though, given increased costs and inflation, the news it offers no doubt not as cheery as it looks.

Sawis also has a bar chart showing that post-2006 decline accompanied by another jagged rising line: this one indicates that, although there have been fewer vineyards, production has been rising inexorably (until, perhaps the last couple of harvests). This surely means that vineyards are being worked harder and harder. Especially given that many are being allowed to get older than desirable (from a production point of view), this kind of intensive viticulture is unlikely to have good implications for the quality of wine they’re producing.

Where are these nearly 90 000 ha of grapes grown? According to the Sawis infographic, more than a third of them – nearly 32 000 ha – are in the generally hot, irrigated Breede River Valley (Robertson, Breedekloof, Worcester). Sawis lumps together Paarl, Wellington, Franschhoek and Tulbagh to total 14 332 ha. Stellenbosch and Swartland/Darling each have something over 12 000 ha. The only other substantial area is Olifants River, with 8 589. Then come Northern Cape, Cape South Coast, Cape Town (Durbanville, Constantia, etc), and the Klein Karoo, in that order, all somewhere in the 2000 has.

As to what grapes are being grown, the top ten hasn’t changed all that much over the same period since 2006, although the hectarages are generally down, reflecting the general decline. But two of those top ten have shown an increase in plantings since 2006: pinotage not greatly but still an increase and it remains in sixth position over all; and sauvignon blanc, much more emphatically. At the end of 2022 it was in second place behind chenin blanc, having leapt over colombar, cabernet sauvignon and shiraz. At the bottom, cinsaut has pushed out muscat d’Alexandrie, but those two and ruby cab are always tussling around there. Chardonnay and merlot complete the list, in the lower half.

Just outside the top ten (above sadly declining semillon and, rather surprisingly to me, cab franc), pinot noir has done very well, doubling its vineyard area – I’d guess this reflects growth in serious sparkling wine rather than red pinot wines. And at positions 19 and 22 respectively are two red grapes that have risen pretty spectacularly in percentage terms: grenache noir (from 89 ha to 552), and durif/petite sirah (from a measly 7 ha to 408). Grenache blanc, tannat and carignan have also now easily crossed the 100 ha mark.

Rising from zero or near-zero to very little are some varieties from warm southern Europe that are still pretty much in the experimental stage in terms of how they perform locally, and could well be important in our hotter, drier future. Verdelho, roussanne, alvarinho, marsanne, nero d’Avola, viura, assyrtik, piquepoul blanc, counoise, borboulenc, agiorgitiko … some of these are names we’re likely to know better in another decade or so.

And, of course, another variety that we will hopefully be hearing more of has started to rise: pontac. But that’s a different story, told here.

- Tim James is one of South Africa’s leading wine commentators, contributing to various local and international wine publications. He is a taster (and associate editor) for Platter’s. His book Wines of South Africa – Tradition and Revolution appeared in 2013.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.