SA wine history: The Dreyers of Leeuwenkuil – what’s in a name?

By Joanne Gibson, 23 February 2021

I recently had the opportunity to catch up over Zoom with Willie and Emma Dreyer, seventh-generation owners of Leeuwenkuil, a farm described as ‘the gateway to the Swartland’ but historically one of the earliest Paarl farms, established as ‘Schinderkuijl’ in 1693.

Although the Dreyer family has owned Leeuwenkuil ‘only’ since 1851, their connection to the farm goes back much further when you consider that Dreyer stamvader Johannes Augustus Dreyer (who arrived at the Cape from Schleswig-Holstein, Germany in 1713) was married to Sara van Wijk, daughter of Arie van Wijk, Leeuwenkuil’s owner in the early 1700s. By 1705 Van Wijk had planted 8,000 vines, presumably never imagining that his daughter’s 21st-century descendants would expand Leeuwenkuil’s vineyard holdings to over 1,200 hectares!

‘Willie Dreyer grows some of the best grapes in South Africa,’ wrote Tim Atkin in his SA Special Report 2020, awarding 95 points to the Leeuwenkuil Heritage Syrah 2017, which was also named Best Shiraz in Winemag’s Prescient Top 20 Wines of 2020 with a rating of 94.

Quite remarkably, it was only in 2008 that the Dreyers took the decision to start making and selling wine themselves – and harvest 2021 marks a significant milestone as the first vintage to be processed in their own winery on the farm, instead of in rented cellar space.

It seems clear that Leeuwenkuil has a bright future, with the Dreyers the first to acknowledge how fortunate they feel not to have been badly impacted by recent bans on local alcohol sales, because most of their production is exported. However, as regular readers of this column will know, it’s the past that intrigues me. And there certainly is an intriguing twist to the early Dreyer tale…

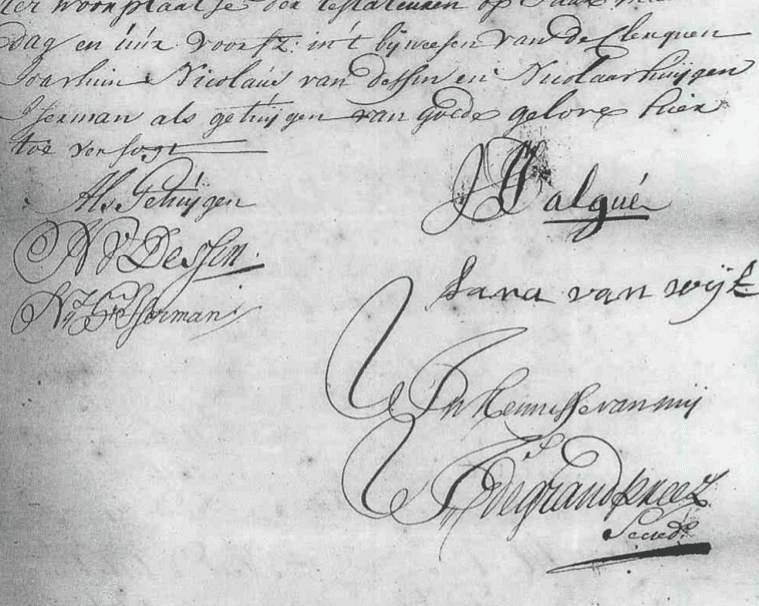

In short, until 21 May 1735, when Sara van Wijk and her husband drew up their joint will, he was known by a completely different name: Isacq d’Algué/Dalgue. The will now declared that his real name was Johannes Augustus Dreijer from Holsteijn and that his children should henceforth use the Dreijer surname in order to have a relationship (omme dus…correspondentie, vriendschap en kennis te kunnen houden) with their family in Europe.

It seems it may only have been after his actual death, on 6 April 1759, that the unusual provision of his will came into effect. I’ve come across numerous estate auctions held throughout the late 1730s and 1740s in which ‘Isack Dalgue’ purchased items ranging from porcelain plates and bedding to building materials and oxen, with everything from books to a birdcage in between.

Who was this mysterious man and what circumstances forced him to adopt an alias and flee to the southern tip of Africa?

All that was known about ‘Ysack Dalgu’ when he disembarked from the Nesserak on 22 November 1713 was that he was a midshipman in his mid-20s. At a time when eligible young women were vastly outnumbered by unmarried men, he must have come across as sufficiently respectable to win the hand of Sara van Wijk on 31 January 1716. Clearly well educated (when many were not), he was soon employed as a messenger of the court at Stellenbosch, becoming a burgher (citizen) in 1724, and from 1727 working as a messenger of the Orphan Chamber (which dealt with the estates of persons who died intestate and left heirs who were minors).

Family legend has it that he fled Germany after killing a love rival in a sword fight. Whether that’s true or not, he was the seventh child of a church minister, so presumably no whiff of scandal would have been acceptable. Or perhaps he was merely drawn to a life of greater adventure than the more constrained one that awaited him as a minister’s son in northern Germany?

While Dreyer eventually revealed his true identity, I can’t help wondering how many young men managed to escape their pasts completely when they arrived at the Cape, so many of them officially named after their (presumed) hometowns rather than their forefathers. Let’s take, fairly randomly, the Cape’s first highly acclaimed winemaker, Jacob Cornelisz van Rosendael – who arrived as a soldier – not to mention his wife, Catharina, who most certainly was rumoured to have had a less than salubrious past (working as a prostitute named Grietjie). And yet their daughter married well, ending up as the mistress of Steenberg.

I love these stories. If you have one, let me know?

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za.

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.