SA wine history: Not-so-humdrum Paarl

By Joanne Gibson, 14 December 2020

3

Despite being the source of many excellent wines, observed my colleague Tim James a few weeks ago, Paarl has a rather lacklustre image. ‘Perhaps the difficulties in building Paarl’s reputation are not to be overcome, despite the inherent quality,’ he mused. ‘Perhaps they could be, and it just needs some dynamic leadership and an infusion of imagination of something more than the humdrum present.’

If Paarl’s present is humdrum, I wondered, what about its past?

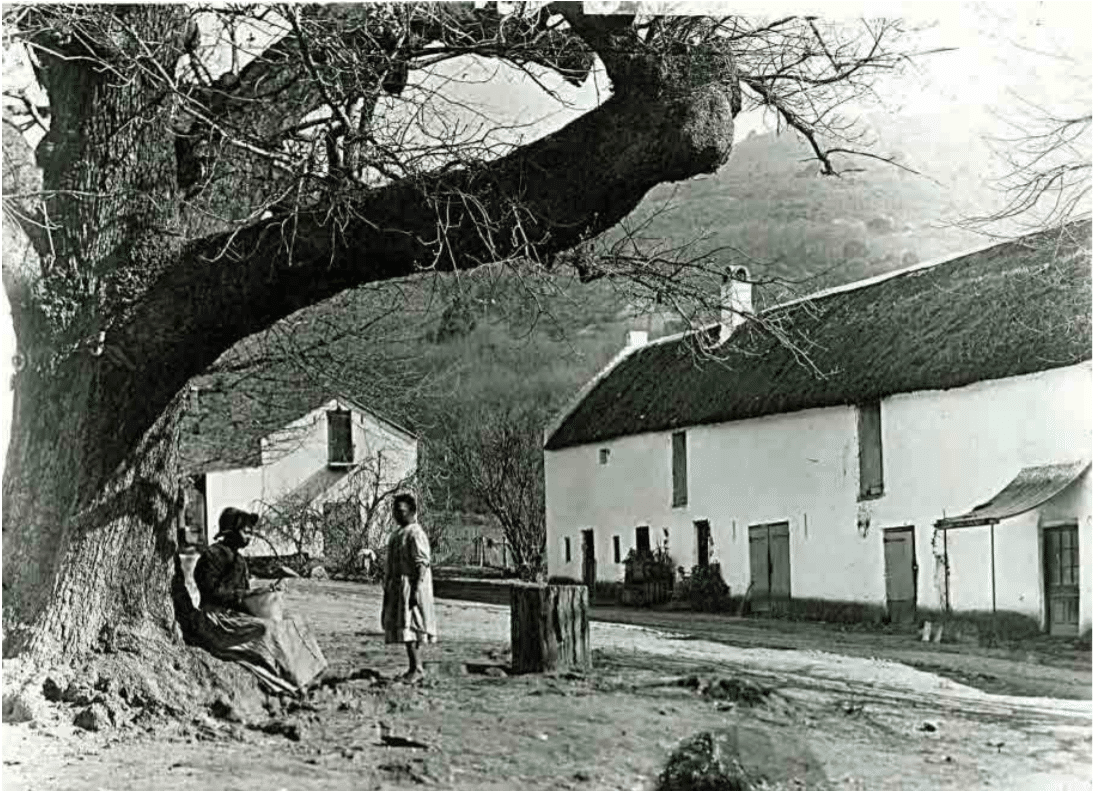

‘Lying along the base of the rocky hill, whose huge granite boulders glistening in the sunshine like monster “pearls” have given it its name, [Paarl] forms one continuous street stretching for nearly seven miles, lined with goodly dwellings, capacious wine-stores, rows of oaks, rose-hedges, gardens and orchards,’ wrote John Noble in his Descriptive Handbook of The Cape Colony, published in 1874. ‘At different points in the breaks between the houses there are glimpses of cultivated vineyards running up the slopes of the hill, and again down towards the bed of the Berg River, while across the valley there are picturesque mountains, whose colourings under the purple light of early morning, or the warm pink of crimson glows of sunset, are exquisitely beautiful.’

Anyone who has enjoyed sundowners at Laborie or the Grande Roche Hotel, for example, will know that this is completely true. Perhaps less true in the modern era is Noble’s next observation: ‘During the greater part of the day the long-extending thoroughfare has a dreamy, tranquil appearance.

‘Nobody is ever hurried or busied or excited,’ he wrote. ‘The community, however, is a wealthy and prosperous one [and] the main source of this, of course, is the wine trade, which is at present very profitable… The various pursuits connected with wine and spirit-making give employment to a great number of the people…and nearly every farm has its large cellars and stores full of huge vats and casks.’

Noble’s Description was written slightly more than a century after the Swedish botanist, Carl Peter Thunberg, visited the Cape, recording: ‘The vineyards near Paarl flourished amazingly, and vines were seen here fifty years old. A vine was said to bear so early as the second year after it was planted, but to yield a full vintage in the third. All the vines here were kept low, in order to make them produce large clusters.’

In Thunberg’s opinion, this great abundance wasn’t entirely a good thing: ‘The gout and dropsy were common diseases in this country, resulting from the great quantities of wine that was drank [sic]…’

So much for quantity; what about quality?

I’ve briefly written previously about a wine that was regarded as ‘the best imitation of Constantia’ in the early 1800s – namely ‘Diamond’ which probably came from the farm Diamant, first granted to Coenraad Cloete in 1693 and today a popular wedding venue (though I’m told it still has a bushvine vineyard producing grapes, which are sold to Fairview next door).

From Drakenstein Heemkring, Paarl’s local history archive (a discovery in itself), I find that Diamant was still ‘famous’ in 1885 when its proprietor, Jacob Jozua Francois le Roux, put it on the market. It then had about 140 000 vines planted alongside orchards, grain fields and meadows; an ‘attractive, spacious and airy’ homestead; and a ‘beautiful’ wine cellar containing some 25 leaguers of sweet wine, 100 leaguers of ‘rijzende wijn’ (still fermenting?) and eight leaguers of brandy.

However, I’ve now come across another Paarl wine that evidently compared favourably with Constantia in the mid-19th century. Writing in 1855, a certain E Blancheton wrote: ‘The sweet wines of Mr Bosman, proprietor vine-dresser at the village of the Paarl, possess qualities nearly equal to those wines called Constantia wines; they are esteemed next in order to them, and are highly valued by connoisseurs.’

The first Bosman in South Africa was Hermanus Bosman from Texel in the Netherlands, who arrived at the Cape in 1707. By all accounts a religious man (not to mention lead singer in the church choir), he was employed as a ‘sieketrooster’ (sick comforter) and on 31 July 1718 was appointed overseer of all Drakenstein church work. It was Bosman who on 1 August 1718 broke earth for the foundation of the new church building at the foot of Paarl Mountain (Paarl’s famous Strooidakkerk) and the farm that had been granted to him on 17 May 1715 was conveniently located right next door – at what we know today as the Grande Roche, previously known as ‘De Nieuwe Plantatie’.

On a part of the farm which later became known as ‘De Oude Plantage’, Bosman laid out a vineyard and made wine – for communion purposes, of course – and it must have been his great-grandson, Izak Johannes, who made the wine ‘highly valued by connoisseurs’ in the mid-1850s, with his great-great-grandson, Jan Daniel, ploughing the proceeds into a more impressive homestead in about 1876.

After Thomas Hardy, the so-called ‘Father of the South Australian Wine Industry’, visited South Africa in 1898, he wrote an article for The South Australian Register in which he described Paarl as the country’s ‘principal winegrowing district’. He wrote: ‘A vineyard in Paarl, belonging to Mr. J. Bosman, is said to be the oldest, and it is also stated that the great grandfather of the present proprietor planted the first vines here nearly 200 years ago. A few of these old vines are still in the vineyard, but will have to go, as the place is badly affected with phylloxera, and is being replanted.’

While Hardy didn’t say what grapes were growing, the unnamed author of a pamphlet entitled Viticulture of the Cape Colony, published in London in 1893, was quite specific. (Note: I think the author is most likely to have been the botanist and French professor of viticulture, Pierre Mouillefert, who visited the Cape early in 1889 and first published his findings – in French – in the Revue de Geographie as well as in a standalone pamphlet in 1892.) Whoever it was, the author described seeing Pontac vineyards at Paarl ‘dating from 1707’, and stating that ‘excellent’ sweet wines could be made from this Teinturier grape.

Unfortunately 1707 would have been too early for Hermanus Bosman, who only arrived at the Cape that year and was too busy comforting the sick until 1715. So does this bring us back to Diamant? Well, not necessarily, when you consider how many Paarl farms – some still producing wine today – were officially granted in the 1690s and probably already ‘promised’ and settled well before that.

I have to say that researching Paarl is not proving very easy so far. Where information is available, it doesn’t seem to be correct. Take famous Fairview, for example. According to Wikipedia, it was first granted in 1693 (as Bloemkoolfontein) to Steven Vervey [sic], ‘thought to be one of the French Huguenots who arrived in the Cape in 1688’.

Actually his name was Steven Vermey and he was Dutch, baptised in Rotterdam on 18 December 1653. What’s more, he sold Bloemkoolfontein within a year to Theunis de Bruyn (who I’m pleased to tell you had planted 6 000 vines by 1700).

Suffice it to say that I have my work cut out for me in 2021.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anonymous (probably Pierre Mouillefert), Viticulture of the Cape Colony, printed by Edward Stanford, London, 1893

Noble, John: Descriptive Handbook of The Cape Colony: Its Conditions and Resources, JC Juta, Cape Town, 1875

Thunberg, Carl Peter: Travels at the Cape of Good Hope 1772-1775, based on the English edition (London 1793-1795), edited by Emeritus Prof. VS Forbes, Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 1986

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za.

Tim James | 14 December 2020

Joanne’s mention of Diamant took me back to the mid 1990s when the farm had a brief brush with something like fame. After half a century of producing no wine (just selling off the grapes), Niel Malan started making some red wine in 1992 in rustic fashion – foot-stomping the grapes, bottling the wine unfiltered. Platter 1996 edition gave both the the Diamont Rouge 94 (cab and merlot) and the Pinotage 94 four stars. They were very cheap for the quality, and I remember going out to the farm to buy some. But by the end of the century, the venture had collapsed, and grapes were again all going elsewhere, mostly to Fairview and Simonsvlei, according to Platter 2000.

By the way, this bit of digging reminded me of just how indispensable Platter is as a source of modern historical knowledge – it’s a real problem for future versions of Joanne seeking information that some producers no longer take part in it.

Joanne Gibson | 14 December 2020

I love the 1996 guide’s description of Diamant: ‘One of those story book wine places, the whole family piling in, no formalities, the results as raw and beautiful as nature can make them.’

I also love the description of the 4 Star Diamant Rouge 1994: ‘A crushed-by-feet, no-filtration dream of a wine… There’s untrammelled joy here: plums, nutmeg, nuts, marzipan. Honest juiciness and a bit of untamed tannin. 13% alc; 60% cabernet with 40% merlot. Bush vines.’

Kwispedoor | 14 December 2020

If memory serves, those wines cost R10 per bottle from the farm at the time. Foot-trodden in large plastic bins and made unfiltered – the resulting wines containing dense sediment, even in their youth. They were rather delicious. In 1995 they made a very interesting and tasty 20.5% ABV port from pinotage (I still have an empty bottle).