SA wine history: Did Napoleon drink Citrusdal wine? (Part Three)

By Joanne Gibson, 16 October 2020

4

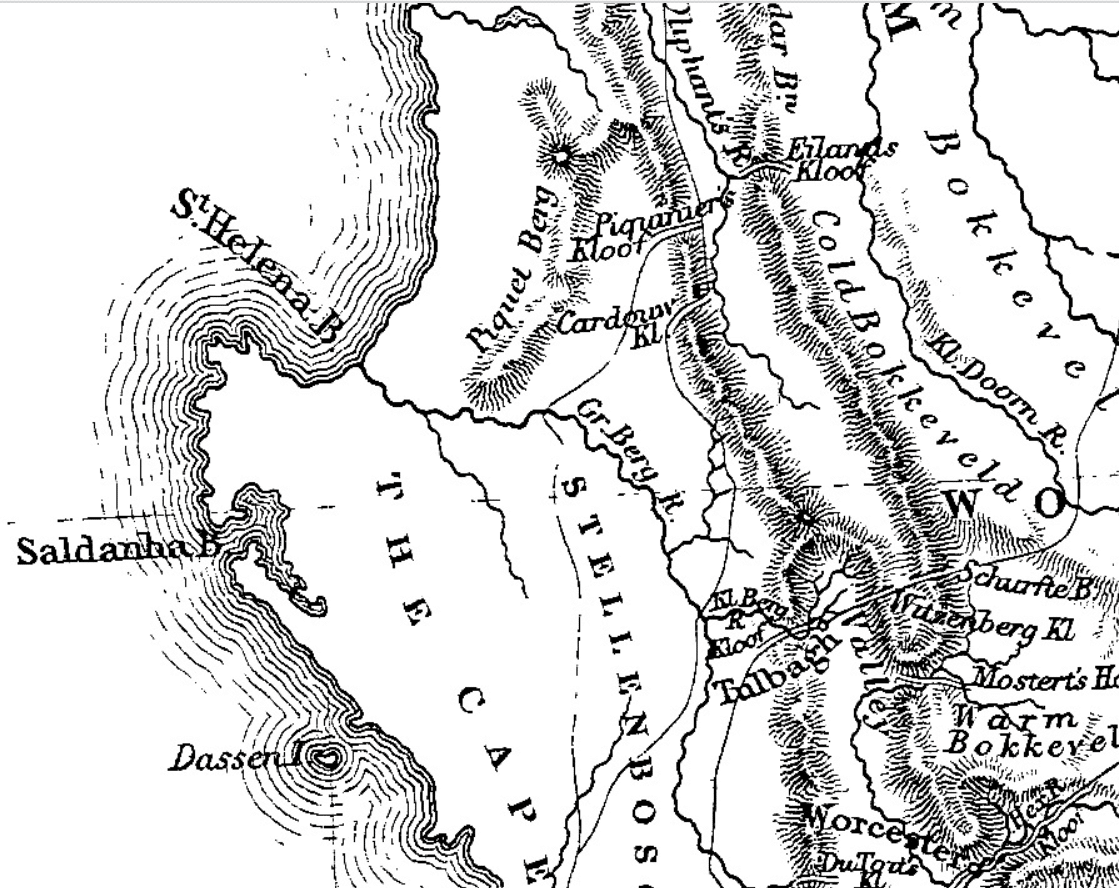

In my last column, I presented the Moutons of Brakfontein as a potential source of wine possibly sent to Napoleon while in exile on St Helena: their name prominently displayed (unlike anyone else’s) on John Tallis’s 1850 map of the Cape Colony, their nagmaal wine ‘famous’.

Needless to say, the Moutons and their various in-laws (including the Lubbes who owned Brakfontein during Napoleon’s time) had been in the Upper Olifants River area for a very long time – and for those of you who think, like I did, that it must have been too far off the beaten track for wine or indeed any other produce to be transported to Table Bay, it’s interesting to note a few things.

Firstly, explorers had been hot-footing it northwards ever since Jan van Riebeeck’s arrival in 1652, hoping to find the legendary gold fields of Monomotapa. In December 1660, Jan Danckaert and his men were finally shown a route over the mountains by a group of San hunter-gatherers. They saw more than 200 elephants on the banks of the river below – hence the name Olifants River – and among the explorers was Pieter van Meerhoff, the Danish onderbarbier (junior surgeon) who would make the return trip five more times before marrying the Khoe translator Eva/Krotoa in 1664. Suffice to say, the so-called ‘Grootte Clooff’ was well known by the time the Second Khoi-Dutch War broke out in 1673, when soldiers known as ‘piqneniers’ (pikemen) were sent there in the vain hope of trapping the Cochoqua chief, Gonnema; hence the name Piekenierskloof.

Serious colonial expansion was fairly limited until smallpox decimated up to nine-tenths of the indigenous population in 1713, after which increasing numbers of grazing permits and loan farms were granted beyond the Berg River. Notably, French Huguenot progenitor Jacques Mouton leased a farm ‘over het Vier en Twintig Rivieren’ (near what is now Porterville), registering it in 1714 as Steenwerk (after his birthplace in Flanders) and planting 5,000 vines.

In the Olifants River Valley, just to the northeast, the first loan farms were allocated in 1725, and by 1732 virtually the entire length of the river had been ‘colonised’. At first, these were mere cattle posts but once crops were cultivated they became settled, built-up, family farms.

For Barend Lubbe, orphaned young, taking over Johannes Basson’s lease on Groote Valleij (just north of Citrusdal town today) proved very advantageous, especially after Khoisan hostilities flared up in the late 1730s. He was appointed veldkorporaal and a military post was set up further upstream ‘aan ter Warme Bad’ – the first official mention of this natural hot spring. After peace was restored, it didn’t take long for acting governor Daniel van den Henghel to order that a ‘handsome stone building’ and ‘thatched bathing huts’ be built at what duly became known as the ‘Company Baths’.

The Baths are still there today (about 18km south of Citrusdal), and I suspect their importance during the 1700s and 1800s has been forgotten. Unlike the natural hot springs at Caledon, which even slaves and Khoekhoen could use for healing purposes, the Olifants River facilities were for the exclusive use of Political Council members and wealthier burghers who had the governor’s permission. In 1763 governor Rijk Tulbagh authorised some repairs and improvements, appointing Matthijs Pielat to keep an eye on things as ‘Posthouder aan’t Warm Bad gelegen over d’Olifants Rivier’, and in 1768 deputy governor JW Cloppenburg proposed building additional facilities.

This seems to have happened because when Swedish botanist Carl Thunberg and Scotsman Francis Masson (Kew Gardens’ first plant collector) visited the baths in October 1773, Thunberg noted that there were now several bathing huts: ‘All of them have three or four steps going into the water for the bathers to sit on, and are also floored on one side for the bathers to lie on.’

Exactly thirty years later, in October 1803, the German physician, botanist and zoologist Hinrich Lichtenstein recorded his arrival at the foot of the Piekenierskloof Pass: ‘The house in which we were to take up our abode for the night belonged to a widow Coetzè, and was at this moment full of guests, some going to the warm bath at the Elephants-river, some returning from it.’

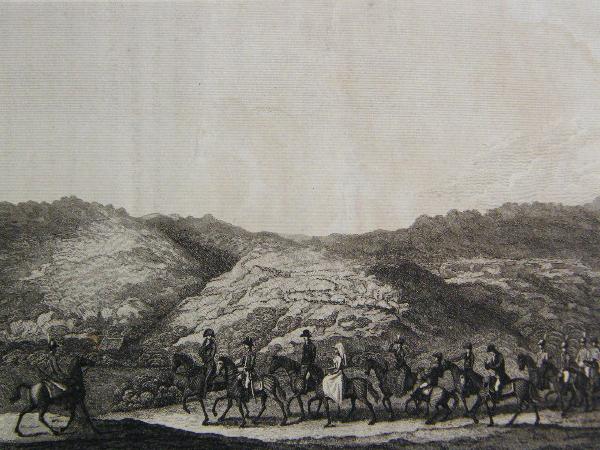

If that alone doesn’t indicate a fair amount of traffic to the hot springs (and beyond), then consider the fact that Lichtenstein’s own party (not counting 12 Khoi servants and four slaves) comprised 25 travellers, including commissioner-general Jacob Abraham de Mist, who was accompanied not only by one of his sons but also by his daughter, Augusta, her friend, Mietjie Versveld, and their maids!

‘Our travelling party was embellished in a very agreeable manner by the addition of female society,’ wrote Lichtenstein, recording that everyone rode horses (‘some of which were always led by the slaves, to render the fatigue less’) accompanied by six ox wagons laden with ‘a large provision of dry food and liquors’ as well as equipment including tents, field-beds, mattresses, bolsters and woollen coverlets ‘to sleep well after the fatigues of the day’.

Going back to 1773, it’s interesting to note some of the names mentioned by Thunberg: ‘We proceeded along the valley to Barent Lubbe’s farm, past Pickenier’s Kloof, and Matton’s farm, which lay to the left of us.’ (Matton’s farm being that of Johannes Paulus Mouton, introduced last time, and Barent Lubbe’s farm being Groote Valleij, given that Thunberg and Masson only later made their way to ‘young Barent Lubbe’s, at the end of the cleft’, i.e. Brakfontein).

But what’s especially noteworthy about the Thunberg/Masson journey is that they didn’t use the Piekenierskloof Pass (although they did send their ox wagon and a damaged cart back that way after opting to explore the Koue Bokkeveld on horseback). To reach the Upper Olifants River, they used a pass 25km to the south, a pass completely forgotten since 1857 when Thomas Bain opted for the Piekenierskloof to build what he called Grey’s Pass. Leading much more directly to the hot springs, this was the Cardouw Pass (also written as Cartouw/Cardow/Kardouw, from the Khoisan for ‘narrow passage’) and it was a shortcut over the mountain, if not always an easy one.

‘This passage,’ wrote Masson, ‘is remarked for being one of the most difficult in this part of Africa; which we found true, being obliged to lead our horses for three hours amidst incessant rain which made the road so slippery that, by often tumbling among the loose stones, they had their legs almost stripped of the skin; and the precipices were so steep, that we were often afraid to turn our eyes to either side. Towards sunset, with great labour and anxiety, we got safe to the other side.’

Thunberg likewise recorded ‘the frequent tumbling of the cattle, owing to the slipperiness of the road, which was occasioned by incessant rains’. Yet even in a dangerous downpour, the crossing only took three hours – and when English civil servant Sir John Barrow travelled from the opposite direction in May 1798, he didn’t deign to describe it at all! For the sons and daughters of established Vier-en-Twintig Rivieren farmers, like Jacques Mouton at Steenwerk, or Willem and Andries Burger at Houd Constant, travelling to and fro over the Cardouw pass while they established themselves in the Upper Olifants River valley was probably no trouble at all.

As for Thunberg and Masson, they arrived ‘wet and terrified’ at ‘a miserable cottage belonging to a Dutchman’ (to quote Masson). The Dutchman was Barend Lubbe’s brother-in-law, Willem Burger, who had loaned this farm – named Cartouw – since 1756. However, Burger’s grandfather (the above-mentioned Willem of Houd Constant) had loaned the adjacent farm, Misgunt, since 1726, and Misgunt was now loaned by Willem’s cousin, Schalk Willem Burger, who also fully owned Halve Dorschvloer next door. Known as Karnemelksvlei today, with its homestead dated 1767, this is where Thunberg and Masson enjoyed a ‘hearty breakfast’ before taking the waters.

It seems Schalk Willem Burger profited from his proximity to the baths, not only selling fresh produce to visitors (as noted by Cloppenburg in 1768) but also hosting them quite comfortably, judging from the household utensils listed in his deceased estate inventory of 24 September 1782: 60 porcelain plates, 20 porcelain serving bowls, nine wine glasses plus five ceramic wine cups, two porcelain as well as four metal teapots, two sets of teacups and saucers, 10 iron cooking pots, four cake pans and copper items including a tart pan, coffee pot and candlesticks (among many other niceties). He also had 25 slaves, 48 oxen, 200 goats, 253 cows and 3,002 sheep; farming equipment including 11 wine leaguers (±575-litre barrels); and three ox wagons (one of them brand new).

Barend Lubbe’s estate inventory of 30 July 1785 was similarly well endowed (29 slaves, 12 leaguers, 60 plates, etc), and his estate auction, held over two days, attracted 68 buyers, 44 of whom travelled more than a day to reach Groote Valleij. Those who came from Cape Town (at least six days by ox wagon) included Lubbe’s son-in-law, Gerhardus Munnik, a former Rondebosch wine pachter (who bought 1,400 sheep). And the items which commanded the highest prices (after land and slaves) were Lubbe’s four wagons – three yoked for oxen and one for horses.

These veritable fleets demonstrate that Olifants River farmers like Lubbe and Burger were more than adequately equipped to travel Caabwaards and back, several decades before Napoleon’s time on St Helena. ‘Long, slow travel by ox wagon was not just a necessity, it was commonplace,’ argues historian Laura Mitchell. ‘Such travel was important link between Cape Town and the outlying areas, especially frontier regions like the Olifants River.’

Of course crossing the Piekenierskloof or even the Cartouw pass was challenging. ‘The rugged wildness of these lofty regions, the gigantic masses of naked rock, the tremendous height from which one looks down upon the precipices below, makes it almost incomprehensible how a heavily loaded waggon should ever reach the summit,’ marvelled Lichtenstein.

But those passes were crossed, not only by well-equipped local farmers on a regular basis but also by travellers making their way to the hot springs and beyond, sometimes in astonishingly large groups.

If you then consider that the Olifants River produced at least one excellent wine that was ‘famous’ during the 1800s, do you still think the Napoleon claim should be dismissed out of hand? I don’t.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lichtenstein, Henry: Travels in Southern Africa, in the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, and 1806, translated from the original German by Anne Plumptre, Henry Colburn, London, 1812

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za.

Angela Lloyd | 19 October 2020

Gosh, Joanne’s sleuthing does turn up some fascinating history, which makes great reading. These articles in particular really do take time and effort to create; thanks Joanne.

Rioja | 16 October 2020

fantastic – thank you

horse | 16 October 2020

Stop flogging a dead horse

Hennie C | 16 October 2020

I will never understand an ignoramus like you. If you don’t find something interesting, don’t read it. It is quite simple. As simple as you are.