SA wine history: A pandemic of the past

By Joanne Gibson, 17 March 2020

Coronavirus is here, as Tim James wrote over the weekend, prompting me to look at a ‘pestilence’ that arrived at the Cape exactly 307 years ago, in March 1713.

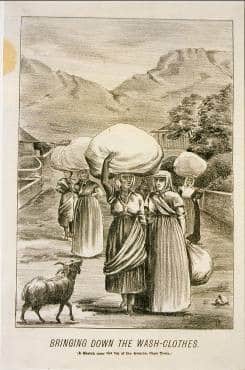

It was smallpox, of course, and it was said to have been introduced when contaminated clothing was sent ashore for washing at the Company’s slave lodge, where slave women reportedly became the first to contract the disease as a result of handling the laundry. However, it’s now known that Variola major is rapidly inactivated even on heavily contaminated surfaces (unlike COVID-19, alas) and it’s also known that the slave lodge functioned as a brothel. It therefore seems probable that far more intimate person-to-person infection took place…

Of the Company’s 520 slaves, almost 200 of both sexes died within the next six months. By 11 June, 160 vrijburghers (free citizens) had been ‘carried off’, and by July the death rate was so high that it had become necessary to bury the dead without coffins, in shallow graves that inevitably attracted scavengers.

‘Even the poor Hottentots are not free,’ recorded the Company journal on 6 May, noting that unlike immigrant adults who may have survived smallpox in childhood, the Khoi had no immunity and were therefore ‘very disastrously smitten’. On 19 May, the journal further recorded: ‘Today the news was received that some of the surviving Cape Hottentots, who wished to escape the sickness by fleeing over the mountains to another tribe, have mostly been killed by the latter – with the exception of a few who escaped – for fear that the pox should break out among them: a rigorous policy.’

A rigorous policy I hope never to see repeated, although fights breaking out over toilet rolls don’t suggest human nature has improved much over the centuries.

Weak jokes aside, historians have attempted to determine the extent to which the Khoi population was decimated, with some estimating losses of up to 90%. (They based this extremely high estimate on the Company journal entry of 13 February 1714 which stated that a number of tribesmen had arrived from the Piketberg region, claiming that ‘scarcely one out of ten members of their society had survived’.)

But even if the mortality rate was ‘only’ 30% (the figure modern researchers seem to agree on for an unvaccinated population with an infection rate of around 75%), this represents a terrifying loss of life which, along with the Khoi’s loss of grazing land to ever-encroaching white settlement and the loss of their cattle to recurring bouts of foot-and-mouth disease, broke down their social structure almost completely.

Thanks to the Company’s taxation lists (Opgaafrolle), it’s possible to get a much better idea of how the vrijburgher population was affected, both in the Cape (the settlement we now know as Cape Town and its suburbs) and on farms in the country.

At the end of 1712, Robert Ross worked out, there were 1,985 vrijburghers (excluding the European servants who were known as knegts), of whom 629 were men, 361 were women and 995 were children. At the end of 1713, there were 1,585, of whom 517 were men (down almost 18%), 286 were women (down almost 21%) and 782 were children (down almost 21.5%).

The population at the Cape (Cape Town) dropped by more than 25% (from 879 to 654) while in the less densely populated outlying areas (where it was somewhat easier to avoid contact with the sick) it dropped by less than 20% from 1,111 to 891.

Suffice it to say that I hope modern South Africans are taking self-isolation very seriously, ideally with a very well-stocked cellar.

Regular readers of this column have already ‘met’ some of the people who lost their lives in 1713. One of them was Maria Everts, the freed slave of West African origins who had become one of the Cape’s wealthiest landowners in her own right by the time of her death, leaving her children quite well off – most notably her son, Johannes Colijn, the man who went on to make Constantia wine famous from the mid-1720s.

Another was Gerrit ‘Grof’ Visser of Blaauwklippen fame (or infamy?) along with his Cape-born wife, Jannetje Thielemans, who both died at the historic farm De Brakke Fonteijn near present-day Philadelphia.

While smallpox failed to fell the formidable widow of Rustenburg, Sophia Schalk van der Merwe, it claimed her second husband, Pieter Robberts, as well as her eldest daughter, Margaretha Pasman, and son-in-law, Nicolaas Elberts, who owned the Hottentots-Holland property Onverwacht (originally part of Vergelegen).

Meanwhile, the ‘colony’ known as Drakenstein (stretching from Franschhoek through Paarl to Wellington) seems to have been particularly badly affected, with the Company journal recording on 25 June 1713 that there were ‘not 20 healthy people’ living there – and noting on 28 November that people were ‘still afflicted’. According to Drakenstein Heemkring: Paarl’s Local History Archive, those who died included:

- Anna Fouché of the farm Cabrière in Franschhoek (survived by her husband, Pierre Jourdaan, and their three minor children);

- Henning Villion of Watergat in Simondium (survived by his wife, Marguerite-Therese de Savoye, and his son, also named Henning, but joined in death by his mother, Cornelia Campenaar, and his siblings, Pieter, Anna, Johannes and Francina);

- Bastiaan Pyl of the farm Kunnenburg in Simondium (you may recall the gruesome suicide of his father, the first owner of Groenerivier – now Alto and Webersburg);

- Jacobus van As who owned the farm Nuwedorp in Groot Drakenstein as well as Wittenberg in Noorder Paarl;

- Abraham Vivier who owned Schoongezicht in Daljosaphat;

- The Klein Drakenstein farmers Salomon de Gournay of Hartebeeskraal-Amstelhof, Wemmer Pasmann of Winterhoek and La Roque, Marthe le Febre of Lustigan, and Casper Jansz of Orleans;

- The Paardeberg farmers Martin Pouisson of Slent, Dirk Dirksze van Schalkwijk of Het Slot van de Paarde Berg, and Dirk Verweij who also owned property in Table Bay and on the Liesbeeck River; and

- The Wellington farmers Heinrich Venter of the Agter-Groenberg farm Vleeschbank, and Gideon Malherbe, who owned two Bovlei farms, namely Hexberg and Groenfontein.

(To name just a few instead of merely quoting numbers…)

Who knows how this current pandemic is going to play out, in the Cape winelands, in South Africa, and across the globe. All I can do is leave you with one final, much happier journal entry from 11 December 1713, by which time the epidemic had passed: ‘Fine harvest and wine season. Have not sufficient quantity of casks to hold the wine.’

Stay as safe as possible and be generous, whether it’s with the toilet paper in your shopping trolley or that special bottle on your dinner table.

- Joanne Gibson has been a journalist, specialising in wine, for over two decades. She holds a Level 4 Diploma from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust and has won both the Du Toitskloof and Franschhoek Literary Festival Wine Writer of the Year awards, not to mention being shortlisted four times in the Louis Roederer International Wine Writers’ Awards. As a sought-after freelance writer and copy editor, her passion is digging up nuggets of SA wine history.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

Comments

0 comment(s)

Please read our Comments Policy here.