Daisy Jones: What separates a good meal from a tremendous meal?

By Daisy Jones, 21 April 2020

1

For obvious reasons, I haven’t reviewed a restaurant this month. Instead, I’ve been making a family cookbook.

It got me thinking. Restaurant food and home food are perceived differently. Fine dining is supposed to inspire, with its skill, artistry and innovation. Home cooking is more functional. It takes shortcuts, it’s often frumpy.

But making this cookbook is inspiring me, as much as any restaurant has in the past ten years. It’s reminding me how meaningful food is to me. My siblings and I adored my mother’s meals. When I became a mother, food became so much a part of our family life: the shopping for it, the cooking of it, the smells of it, the running out, the arguing over the last slice and the cleaning up after it. Like my mother, I show love through feeding. I often cook three times a day, nothing fancy, but the gas clicks on morning, noon and night.

I wonder how South Africa’s best and most promising chefs are reflecting on home food during lockdown. Restaurants are closed. Overnight, ready or not, all our chefs have become home cooks. Did they welcome the break from fussing and fiddling with sauces and foams? Did they eat Otees and toast for a fortnight? And what are they doing now? I wonder how many have sharpened their knives recently and turned their attention to feeding lovers, spouses or children with dishes their mothers made them. Because it makes sense. At home, if you’re entertaining, you might go into cheffy mode. But when it’s just your nearest and dearest, it comes back to family cooking.

I sincerely hope that this lockdown will narrow the gap between fancy restaurant food and home cooking in our country. There are several reasons why.

Number one is food culture. All around the country right now people are cooking in ways that reflect their cultural heritage. It’s not neat. There aren’t boerekos households and Indian curry households. It’s a mishmash, but we all come from somewhere. My great grandfather had a fish and chip shop in North Yorkshire. Every Sunday morning, his brother Jim used to bring vegetables from his allotment garden to cook with the Sunday roast. My mother ate Grandpa Walter’s fish and chips, and Nana’s roasts. When I was a child my mother made us roasts with Yorkshire puddings – and bubble-and-squeak on Mondays with the leftover veg. I can hardly see the sea, especially in winter, without wanting a piece of deep-fried, battered fish and a parcel of hot chips fragrant with salt and brown malt vinegar. As Michael Pollan says in his 2008 book In Defence of Food, “Culture … at least when it comes to food, is really just a fancy word for your mother.”

In my view, one of the most profound ways of growing a national cuisine – or a regional cuisine, or even a restaurant style – is for chefs to really acknowledge how much the food of their childhoods and their family has shaped them. The tastes and kitchen lessons of home are surely deeper influences than any amount of training in classical French techniques. We don’t want our chefs to be wannabes. We want them to innovate with their deepest knowledge. It makes sense that chefs have the greatest creative scope when they play within the realms of what they know best.

Take David Chang, one of the world’s most famous chefs, celebrated for his merging of food cultures (in a miso pizza, for example). Chang has 24 Michelin stars to his name. Recently, he created, produced and starred in the Netflix series Ugly Delicious.

“Home cooking, what I call ‘ugly delicious food’, has now become the food that I also want to make in the restaurant,” he says.

“When you’re a younger cook, you want to learn ideas that have nothing to do with what you grew up in. And I wanted nothing to do with Korean food. I wanted nothing to do with anything of my upbringing. And then things come full circle, right?”

Chang is now interested in creating food that is layered: it’s delicious in itself, but it also evokes memories of deliciousness.

“It’s like when you eat a dish that’s not even roast chicken but reminds you of roast chicken cooked by your mom. That’s where you want to be at in cooking.”

Science is on Chang’s side in this endeavour. It is possible in cooking to conjure memories, and thereby to enhance the deliciousness of a dish. To do this, you use aroma. Smell, not taste, evokes memories.

According to Bill Bryson in his 2019 The Body: A Guide for Occupants, “When we smell something, the information, for reasons unknown, goes straight to the olfactory cortex… where memories are shaped…,” Luckily for chefs, “smell is said to account for at least 70 percent of flavour and maybe as much as 90 percent.”

As home cooks and diners it’s our moral imperative to encourage our chefs to dig deep. When we glorify French cuisine – or Nordic, or Japanese – we devalue the food cultures of our chefs. Food snobbery happens at a more local level too. We may think a chef’s braaiing skills are more appropriately employed in a fine dining context than his female colleague’s low-and-slow stewing techniques.

Of course there is a gender angle to the restaurant vs home food debate. Male restaurant chefs are often characterized as artistic pioneers, while female home cooks are characterized as uneducated. If we don’t close the divide between home cooking and restaurant cooking, we will encourage flashy heartlessness in restaurants, and convenience meals at home – because why make supper if society derides home cooking?

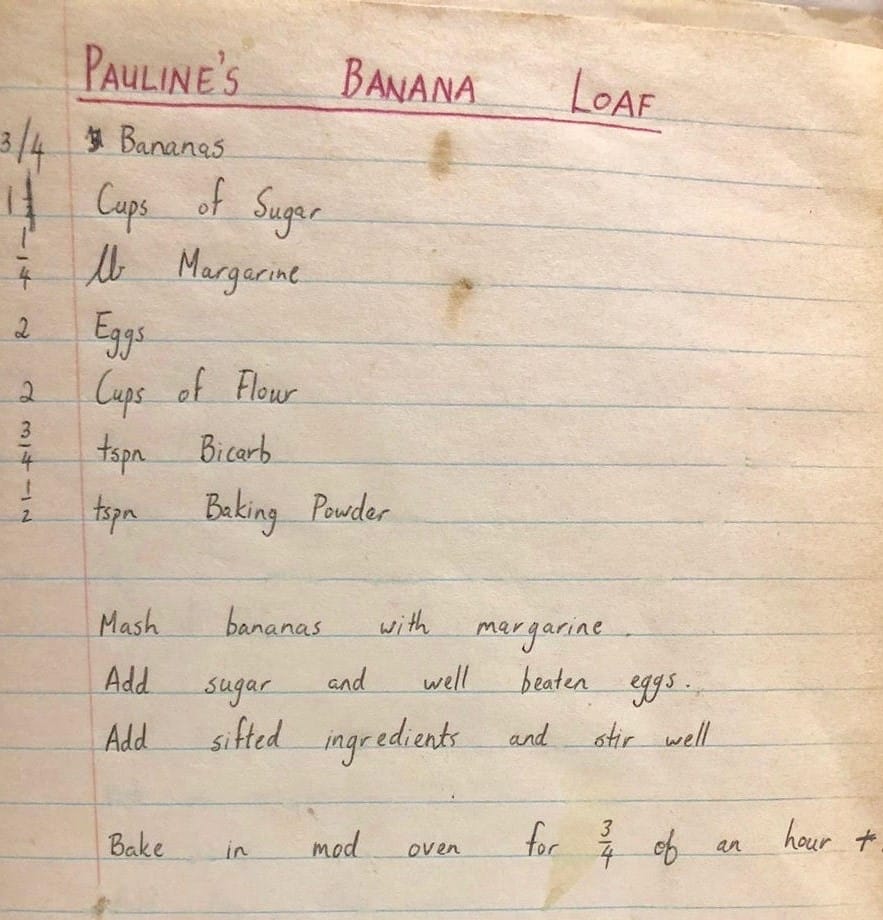

For my part, I’m determined to finish what we’re calling The Big Family Cookbook (or The BFC), even if it’s just to save my daughter the trouble of searching around the house for scraps of paper when she wants to make “Pauline’s Banana Bread” or “Grandma’s Flapjacks”.

Chang says: ”Food that I like has a sense of community, a narrative that’s being told and oftentimes, as cliché as it sounds, it’s food that’s made with love. That’s what separates a good meal versus a tremendous meal.”

That would look just as good quoted on a fine dining menu as it would on the first page of our BFC. Don’t you think?

- Daisy Jones has been writing reviews of Cape Town restaurants for ten years. She won The Sunday Times Cookbook of the Year for Starfish in 2014. She was shortlisted for the same prize in 2015 for Real Food, Healthy, Happy Children. Daisy has been a professional writer since 1995, when she started work at The Star newspaper as a court reporter. She is currently completing a novel.

Attention: Articles like this take time and effort to create. We need your support to make our work possible. To make a financial contribution, click here. Invoice available upon request – contact info@winemag.co.za

JP | 22 April 2020

Thanks Daisy, this touches on the vital point that our chefs need to be rooted, or return to their roots, if our restaurants are to evolve. Maybe this lock-down phase will (ironically) play a part in encouraging this.